Greater Finland

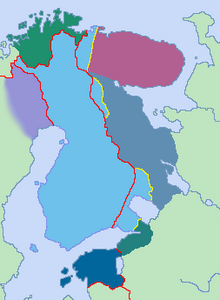

The most common concept saw the country as defined by natural borders encompassing the territories inhabited by Finns and Karelians, ranging from the White Sea to Lake Onega and along the Svir River and Neva River—or, more modestly, the Sestra River—to the Gulf of Finland.

The concept of Greater Finland was commonly defined by what was seen as natural borders, which included the areas inhabited by Finns and Karelians.

Some extremists also included the Kola Peninsula and Ingria in Russia, Finnmark in Norway, the Torne Valley in Sweden, and Estonia.

In 1837, the botanist Johan Ernst Adhemar Wirzén defined Finland's wild plant distribution area as the eastern border lines of the White Sea, Lake Onega, and the River Svir.

The Greater Finland ideology gained strength from 1918 to 1920, during the Heimosodat, with the goal of combining all Finnic peoples into a single state.

Two Russian municipalities, Repola and Porajärvi, wanted to become part of Finland but could not under the strict conditions of the Treaty of Tartu.

They declared themselves independent in 1919, but the border change was never officially confirmed, mainly because of the treaty, which was negotiated the following year.

This was in line with the Bolshevik leadership's policy at the time of offering political autonomy to each of the national minorities within the new Soviet state.

After the Finnish Civil War in 1918, the Red Guards fled to Russia and rose to a leading position in Eastern Karelia.

Gylling encouraged Finns in North America to flee to the Karelian ASSR, which was held up as a beacon of enlightened Soviet national policy and economic development.

This coincided with increasing centralization under Joseph Stalin and the concurrent decline in power of many local minority elites.

The academic Dmitri Bubrikh then developed a literary Karelian based on the Cyrillic alphabet, borrowing heavily from Russian.

But the new language, based on an unfamiliar alphabet and with extensive usage of Russian vocabulary and grammar, was difficult for many Karelians to comprehend.

This new entity was created with an eye to absorbing a defeated Finland into one greater Finnic (and Soviet) state, and so the official language returned to Finnish.

Despite this, the KFSSR was maintained as a full Union Republic (on a par with Ukraine or Kazakhstan, for example) until the end of the Stalinist period, and Finnish was at least nominally an official language until 1956.

During the Continuation War from 1941 to 1944, about 62,000 Ingrian Finns escaped to Finland from German-occupied areas, of whom 55,000 were returned to the Soviet Union and expelled to Siberia.

[6] During the civil war in 1918, when the military leader Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim was in Antrea, he issued one of his famous Sword Scabbard Declarations, in which he said that he would not "sheath my sword before law and order reigns in the land, before all fortresses are in our hands, before the last soldier of Lenin is driven not only away from Finland, but from White Karelia as well".

On 20 July 1941, a celebration was held in Vuokkiniemi, where White and Olonets Karelia were declared to have joined Finland.

In 1941, the government published a German edition of Finnlands Lebensraum, a book supporting the idea of Greater Finland, with the intention of annexing Eastern Karelia and Ingria.

A 1941 book by professor Jalmari Jaakkola, titled Die Ostfrage Finnlands, sought to justify the occupation of East Karelia.

The main supporter of the idea, the Academic Karelia Society, was born as a cultural organization, but in its second year, it released a program that dealt with broader strategic, geographical, historical, and political arguments for Greater Finland.