Kuban Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Sich, however, represented a safe haven for runaway serfs, where the state authority did not extend, and often took part in rebellions which were constantly breaking out in Ukraine.

[5] In 1775, after numerous attacks on Serbian colonisers, the Russian Empress Catherine the Great had Grigory Potemkin destroy the Zaporozhian Host.

Potemkin suggested that the former commanders Antin Holovaty, Zakhary Chepiha and Sydir Bily round the former Cossacks into a Host of the loyal Zaporozhians in 1787.

[citation needed] During the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774), the Don Cossacks on the Khopyor River took part in the campaign, and in 1770 – then numbering four settlements – requested to form a regiment.

In 1825-1826 the regiment began its first expansions, pushing westwards to the bend of the Kuban River and founding five new stanitsas (the so-called new-Kuban line: Barsukovskaya, Nevinnomysskaya, Belomechetskaya, Batalpashinskaya (modern Cherkessk), Bekeshevskaya and Karantynnaya (currently Suvorovskaya).

The Black Sea Cossacks sent men to many major campaigns at the Russian Empire's demand, such as the suppression of the Polish Kościuszko Uprising in 1794, the ill-fated Persian Expedition of 1796 where nearly half of the Cossacks died from hunger and disease, and sent the 9th plastun (infantry) and 1st joint cavalry regiments as well as the first Leib Guards (elite) sotnia to aid the Russian Army in the Patriotic War of 1812.

The new host participated in the Russo-Persian War (1826–1828) where they stormed the last remaining Ottoman bastion of the northern Black Sea coast, the fortress of Anapa, in 1828.

In the course of the Crimean War of 1853 to 1856, the Cossacks foiled any attempts of allied landing on the Taman Peninsula, whilst the 2nd and 5th plastun battalions took part in the Defence of Sevastopol.

[citation needed] As the years went by, the Black Sea Cossacks continued its systematic penetrations into the mountainous regions of the Northern Caucasus.

To aid them, a total of 70 thousand additional ex-Zaporozhians from the Bug, Yekaterinoslav, and finally the Azov Cossack Host migrated there in the mid 19th century.

All three of the former were necessary to be removed to vacate space for the colonisation of New Russia, and with the increasing weakness of the Ottoman Empire as well as the formation of independent buffer states in the Balkans, the need for further Cossack presence had ended.

The Kuban Cossacks continued to make an active part in the Russian affairs of the 19th century starting from the finale of the Russian-Circassian War which ceased shortly after the hosts' formation.

Rather than a traditional Imperial Guberniya (governorate) with uyezds (districts), the territory was administered by the Kuban Oblast which was split into otdels (regions, which in 1888 counted seven).

Prior to 1870, this system of legislature in the Oblast remained a robust military one and all legal decisions were carried out by the stanitsa ataman and two elected judges.

[citation needed] In 1863, the first periodical Кубанские войсковые ведомсти (Kubanskiye voiskovye vedomsti) began printing, and two years later the host's library was opened in Yekaterinodar.

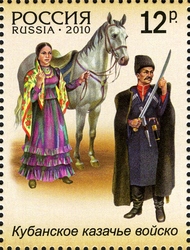

[9] Until 1914 the Kuban Cossack Host wore a full dress uniform comprising a dark grey/black kaftan (knee length collarless coat) with red shoulder straps and braiding on the wide cuffs.

[12] Prior to 1908, individual cossacks from all Hosts were required to provide their own uniforms (together with horses, Caucasian saddles and harness).

[13] The 200 Kuban and 200 Terek Cossacks of the Imperial Escort (Konvoi) wore a special gala uniform; including a scarlet kaftan edged with yellow braid and a white waistcoat.

With his death in June 1918, however, a federative union was signed with the Ukrainian government of Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky after which many Cossacks left to return home or defected to the Bolsheviks.

Additionally, there was an internal struggle among the Kuban cossacks over loyalty towards Anton Denikin's Russian Volunteer Army and the Ukrainian People's Republic.

[17][18][19][20][21] The first collaborators were formed from Soviet Cossack POWs and deserters after the consequences of the Red Army's early defeats in the course of Operation Barbarossa.

[29] Whilst units under the command of General Pavel Belov, the 2nd Cavalry Corps made from Don, Kuban and Stavropol Cossacks spearheaded the counter-attack onto the right flank of the 6th German Army delaying its advance towards Moscow.

[34] The Cossacks have actively participated in some of the more abrupt political developments following the dissolution of the Soviet Union: invasions of South Ossetia, Crimea, Transnistria and Abkhazia and nominally as peacekeepers in Kosovo.

According to human rights reports from the 1990s, the Cossacks regularly harassed non-Russians, such as Armenians and Chechens, living in southern Russia.

Not only is their aid in military affairs important, during the floods in 2004 of the Taman Peninsula they provided men and equipment for relief missions.

On 2 August 2012, the governor of Krasnodar Krai, Alexander Tkachyov announced a controversial plan to deploy a paramilitary force of one thousand unarmed but uniformed Kuban Cossacks in the region to help police patrols.

Like many other Cossacks, some refuse to accept themselves as part of the standard ethnic Russian people, and claim to be a separate subgroup on par with sub-ethnicities such as the Pomors.

The Kuban Cossacks living in Krasnodar Kray, Adygea, Karachayevo-Cherkessia and some regions of Stavropol Krai and Kabardino-Balkaria counted 25,000 men.

In peacetime the Host provided 10 horse regiments making up a Kuban Cossack division, six plastun (infantry) battalions and six horse-artillery batteries; in addition to irregular and support units.

The effectiveness of these units was demonstrated during the war, particularly the Caucasus Front and by 1917 a total of 22 battalions, comprising one division plus four brigades, were on active service.