Lacquer

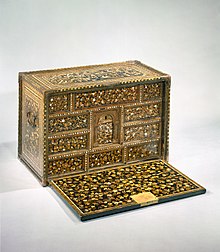

Asian lacquer is sometimes painted with pictures, inlaid with shell and other materials, or carved, as well as dusted with gold and given other further decorative treatments.

In modern techniques, lacquer means a range of clear or pigmented coatings that dry by solvent evaporation to produce a hard, durable finish.

Lacquer finishes are usually harder and more brittle than oil-based or latex paints and are typically used on hard and smooth surfaces.

The English lacquer is from the archaic French word lacre, "a kind of sealing wax", from Portuguese lacre, itself an unexplained variant of Medieval Latin lacca "resinous substance," from Arabic lakk (لك), from Persian lāk (لاک), from Hindi lākh (लाख); Prakrit lakkha, 𑀮𑀓𑁆𑀔),[3][4][5][6] itself from the Sanskrit word lākshā (लाक्षा) for lac bug, representing the number one hundred thousand (100,000), used as wood finish in ancient India and neighbouring areas.

It is used for wood finish, lacquerware, skin cosmetic, ornaments, dye for textiles, production of different grades of shellac for surface coating.

The phenols oxidize and polymerize under the action of laccase enzymes, yielding a substrate that, upon proper evaporation of its water content, is hard.

These lacquers produce very hard, durable finishes that are both beautiful and very resistant to damage by water, acid, alkali or abrasion.

The ornaments woven with lacquered red thread were discovered in a pit grave dating from the first half of the Initial Jōmon period.

Also, at Kakinoshima "A" Excavation Site, earthenware with a spout painted with vermilion lacquer, which was made 3200 years ago, was found almost completely intact.

[14][15][13] During the Shang dynasty (1600–1046 BC), the sophisticated techniques used in the lacquer process were first developed and it became a highly artistic craft,[16] although various prehistoric lacquerwares have been unearthed in China dating back to the Neolithic period.

[16] The earliest extant Chinese lacquer object, a red wooden bowl,[17] was unearthed at a Hemudu culture (5000–4500 BC) site in China.

Until the 19th century, lacquerware was one of Japan's major exports, and European royalty, aristocrats and religious people represented by Marie-Antoinette, Maria Theresa and The Society of Jesus collected Japanese lacquerware luxuriously decorated with maki-e.[20][21] The terms related to lacquer such as "Japanning", "Urushiol" and "maque" which means lacquer in Mexican Spanish, are derived from Japanese.

It is used not only as a finish, because if mixed with ground fired and unfired clays applied to a mould with layers of hemp cloth, it can produce objects without need for another core like wood.

The problem with using nitrocellulose in lacquers was its high viscosity, which necessitated dilution of the product with large amounts of thinner for application, leaving only a very thin film of finish not durable enough for outdoor use.

This problem was overcome by decreasing the viscosity of the polymer (the term actually post-dates the empirical solution, with Staudinger's modern structural theory explaining polymer solution viscosity by length of molecular chains not yet experimentally proven in 1920s) with heat treatments, either with 2% of mineral acid or in an autoclave at considerable pressure.

[26] In 1923, General Motors' Oakland brand automobile was the first to introduce one of the new fast-drying nitrocellulose lacquers, a bright blue, produced by DuPont under their Duco tradename.

[24]: 295–301 In 1924 the other GM makes followed suit, and by 1925 nitrocellulose lacquers were thoroughly disrupting the traditional paint business for automobiles, appliances, furniture, musical instruments, caskets, and other products.

These lacquers were a huge improvement over earlier automobile and furniture finishes, both in ease of application and in colour retention.

The use of lacquers in automobile finishes was discontinued when tougher, more durable, weather- and chemical-resistant two-component polyurethane coatings were developed.

Even though its odor is weaker, water-based lacquers can still produce airborne particulates that can get into the lungs, so proper protective wear still needs to be worn.

[27] As Asian lacquer work became popular in England, France, the Netherlands, and Spain in the 17th century, the Europeans developed imitation techniques.

By the twentieth century, the term was freely applied to coatings based on various varnishes and lacquers besides the traditional shellac.