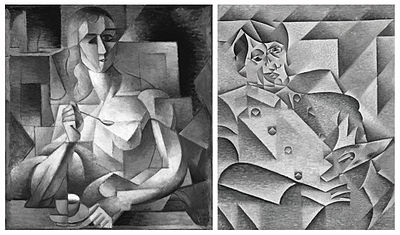

Lady at her Dressing Table

This distilled synthetic form of Cubism exemplifies Metzinger's continued interest, in 1916, towards less surface activity, with a strong emphasis on larger, flatter, overlapping abstract planes.

[2] Painted during the spring of 1916, Femme au miroir formed part of the collection of Léonce Rosenberg, and was probably exhibited at Galerie de L'Effort Moderne in Paris.

The painting was purchased in New York City (at the auction or afterwards) by the American art collector John Quinn, and formed part of his collection until 1927.

The work was subsequently featured at The University of Iowa Museum of Art in the Jean Metzinger in Retrospect exhibition, 1985, and reproduced as a full page color plate in the catalogue.

[3] Femme au miroir, signed "JMetzinger" and dated Avril 1916 on the reverse, is an oil painting on canvas with dimensions 92.4 x 65.1 cm (51 1/16 x 38 1/16 in.).

The vertical composition is painted in a geometrically Cubist style, representing a woman holding a mirror in her left hand, standing in front of a chair and dressing table upon which rests a perfume atomizer.

The woman appears simultaneously clothed and unclothed in an interplay of transparencies, visual, tactile, and motor spaces, evoking a series of mind-associations between past present and future not atypical of Metzinger's earlier works.

Her face is eminently stylized, her neck is tubiform, her hair almost realistic in appearance as if combed onto the canvas; her shoulders, decidedly cubic from which emanate long slender arms superimposed with geometric elements that compose the background.

Metzinger's works from 1915 and 1916 show a more restrained use of rectilinear grids, heavy surface texture and bold decorative patterning.

[5] The Cubist considerations manifested prior to the outset of World War I—such as the fourth dimension, dynamism of modern life, the occult, and Henri Bergson's concept of duration—had now been vacated, replaced by a purely formal reference frame.

[5] This clarity and sense of order spread to almost all on the artists under contract with Léonce Rosenberg—including Juan Gris, Jacques Lipchitz, Henri Laurens, Auguste Herbin, Joseph Csaky and Gino Severini—leading to the descriptive term 'Crystal Cubism', coined by the critic Maurice Raynal.

Each painting represents objects or elements of the real world—such as perfume bottles, moulding of the walls, an ear ring—and human figures.

[2] During 1916, Sunday discussions at the studio of Jacques Lipchitz included Metzinger, Gris, Pablo Picasso, Diego Rivera, Henri Matisse, Amedeo Modigliani, Pierre Reverdy, André Salmon, Max Jacob, and Blaise Cendrars.

In a letter written in Paris to Albert Gleizes in Barcelona during the war, dated 4 July 1916, Metzinger writes: After two years of study I have succeeded in establishing the basis of this new perspective I have talked about so much.

Painting, sculpture, music, architecture, lasting art is never anything more than a mathematical expression of the relations that exist between the internal and the external, the self [le moi] and the world.

(Metzinger, 4 July 1916)[6][7]The 'new perspective' according to Daniel Robbins, "was a mathematical relationship between the ideas in his mind and the exterior world".

[6] In a second letter to Gleizes, dated 26 July 1916, Metzinger writes: If painting was an end in itself it would enter into the category of the minor arts which appeal only to physical pleasure... No.

His entry at the 1912 Salon des Indépendants, Hommage à Pablo Picasso, was also an homage to Metzinger's Le goûter (Tea Time).

[10] As art historian Peter Brooke points out, Gris started painting persistently in 1911 and first exhibited at the 1912 Salon des Indépendants.

[13] This timescale corresponds with the period after which Gris signed a contract with Léonce Rosenberg, following a rally of support by Henri Laurens, Lipchitz and Metzinger.

[14] Metzinger's radical geometrization of form as an underlying architectural basis for his compositions is already visible in his work circa 1912–13, in paintings such as Au Vélodrome (1912) and Le Fumeur (1913).

[2] Metzinger's evolution toward synthesis has its origins in the configuration of flat squares, trapezoidal and rectangular planes that overlap and interweave, a "new perspective" in accord with the "laws of displacement".

In the case of Le Fumeur Metzinger filled in these simple shapes with gradations of color, wallpaper-like patterns and rhythmic curves.

The synthetic manipulation of abstract geometric shapes, or "mathematical expression of the relations that exist between the le moi and the world", to use the words of Metzinger, was the ideal metaphysical starting point.

[15] For the occasion of the Léonce Rosenberg sale, Lady at her Dressing Table was reproduced in an article published in The Sun (New York, N.Y.).

[17] The acquisition was preceded by a lively correspondence between Quinn, the gallery manager Harriet Bryant, and the artist's brother Maurice Metzinger.

The event included works by Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Henri Matisse, André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, Robert Delaunay, Jacques Villon, Gino Severini, and Raymond Duchamp-Villon; in addition to American artists Arthur B. Davies, Walt Kuhn, Marsden Hartley, Stanton Macdonald-Wright, and Max Weber.