Lagrange point

Currently, an artificial satellite called the Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) is located at L1 to study solar wind coming toward Earth from the Sun and to monitor Earth's climate, by taking images and sending them back.

The European Space Agency's earlier Gaia telescope, and its newly launched Euclid, also occupy orbits around L2.

From that, in the second chapter, he demonstrated two special constant-pattern solutions, the collinear and the equilateral, for any three masses, with circular orbits.

[8] Earlier examples include the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe and its successor, Planck.

Any object orbiting at L1, L2, or L3 will tend to fall out of orbit; it is therefore rare to find natural objects there, and spacecraft inhabiting these areas must employ a small but critical amount of station keeping in order to maintain their position.

As the Sun and Jupiter are the two most massive objects in the Solar System, there are more known Sun–Jupiter trojans than for any other pair of bodies.

Known objects on horseshoe orbits include 3753 Cruithne with Earth, and Saturn's moons Epimetheus and Janus.

The ratio of diameter to distance gives the angle subtended by the body, showing that viewed from these two Lagrange points, the apparent sizes of the two bodies will be similar, especially if the density of the smaller one is about thrice that of the larger, as in the case of the earth and the sun.

Additionally, the geometry of the triangle ensures that the resultant acceleration is to the distance from the barycenter in the same ratio as for the two massive bodies.

The radial acceleration a of an object in orbit at a point along the line passing through both bodies is given by:

For Sun–Earth-L1 missions, it is preferable for the spacecraft to be in a large-amplitude (100,000–200,000 km or 62,000–124,000 mi) Lissajous orbit around L1 than to stay at L1, because the line between Sun and Earth has increased solar interference on Earth–spacecraft communications.

Similarly, a large-amplitude Lissajous orbit around L2 keeps a probe out of Earth's shadow and therefore ensures continuous illumination of its solar panels.

Although the L4 and L5 points are found at the top of a "hill", as in the effective potential contour plot above, they are nonetheless stable.

The reason for the stability is a second-order effect: as a body moves away from the exact Lagrange position, Coriolis acceleration (which depends on the velocity of an orbiting object and cannot be modeled as a contour map)[22] curves the trajectory into a path around (rather than away from) the point.

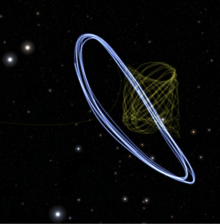

[22][24] Because the source of stability is the Coriolis force, the resulting orbits can be stable, but generally are not planar, but "three-dimensional": they lie on a warped surface intersecting the ecliptic plane.

Distances are measured from the larger body's center of mass (but see barycenter especially in the case of Moon and Jupiter) with L3 showing a negative direction.

Planned missions include the Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe(IMAP) and the NEO Surveyor.

Because an object around L2 will maintain the same relative position with respect to the Sun and Earth, shielding and calibration are much simpler.

Spacecraft generally orbit around L2, avoiding partial eclipses of the Sun to maintain a constant temperature.

From locations near L2, the Sun, Earth and Moon are relatively close together in the sky; this means that a large sunshade with the telescope on the dark-side can allow the telescope to cool passively to around 50 K – this is especially helpful for infrared astronomy and observations of the cosmic microwave background.

Sun–Earth L1 and L2 are saddle points and exponentially unstable with time constant of roughly 23 days.

[9] Sun–Earth L3 was a popular place to put a "Counter-Earth" in pulp science fiction and comic books, despite the fact that the existence of a planetary body in this location had been understood as an impossibility once orbital mechanics and the perturbations of planets upon each other's orbits came to be understood, long before the Space Age; the influence of an Earth-sized body on other planets would not have gone undetected, nor would the fact that the foci of Earth's orbital ellipse would not have been in their expected places, due to the mass of the counter-Earth.

The Sun–Earth L3, however, is a weak saddle point and exponentially unstable with time constant of roughly 150 years.

[9] Moreover, it could not contain a natural object, large or small, for very long because the gravitational forces of the other planets are stronger than that of Earth (for example, Venus comes within 0.3 AU of this L3 every 20 months).

[citation needed] A spacecraft orbiting near Sun–Earth L3 would be able to closely monitor the evolution of active sunspot regions before they rotate into a geoeffective position, so that a seven-day early warning could be issued by the NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center.

Moreover, a satellite near Sun–Earth L3 would provide very important observations not only for Earth forecasts, but also for deep space support (Mars predictions and for crewed missions to near-Earth asteroids).

[27] Earth–Moon L1 allows comparatively easy access to Lunar and Earth orbits with minimal change in velocity and this has as an advantage to position a habitable space station intended to help transport cargo and personnel to the Moon and back.

Earth–Moon L2 has been used for a communications satellite covering the Moon's far side, for example, Queqiao, launched in 2018,[29] and would be "an ideal location" for a propellant depot as part of the proposed depot-based space transportation architecture.

[31] The L5 Society's name comes from the L4 and L5 Lagrangian points in the Earth–Moon system proposed as locations for their huge rotating space habitats.

[35] In 2017, the idea of positioning a magnetic dipole shield at the Sun–Mars L1 point for use as an artificial magnetosphere for Mars was discussed at a NASA conference.

Click for animation.