Rocket engine

Combustion is most frequently used for practical rockets, as the laws of thermodynamics (specifically Carnot's theorem) dictate that high temperatures and pressures are desirable for the best thermal efficiency.

The temperatures and pressures typically reached in a rocket combustion chamber in order to achieve practical thermal efficiency are extreme compared to a non-afterburning airbreathing jet engine.

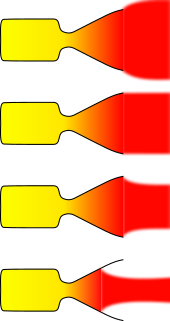

Advanced altitude-compensating designs, such as the aerospike or plug nozzle, attempt to minimize performance losses by adjusting to varying expansion ratio caused by changing altitude.

In addition, significant temperature gradients are set up in the walls of the chamber and nozzle, these cause differential expansion of the inner liner that create internal stresses.

The extreme vibration and acoustic environment inside a rocket motor commonly result in peak stresses well above mean values, especially in the presence of organ pipe-like resonances and gas turbulence.

[26][27][28][25] Such effects are very difficult to predict analytically during the design process, and have usually been addressed by expensive, time-consuming and extensive testing, combined with trial and error remedial correction measures.

To reduce this, and the risk of payload damage or injury to the crew atop the stack, the mobile launcher platform was fitted with a Sound Suppression System that sprayed 1.1 million litres (290,000 US gal) of water around the base of the rocket in 41 seconds at launch time.

The development of the US rocket engine industry has been shaped by a complex web of relationships between government agencies, private companies, research institutions, and other stakeholders.

Universities provide graduate and undergraduate education to train qualified technical personnel, and their research programs often contribute to the advancement of rocket engine technologies.

More than 25 universities in the US have taught or are currently teaching courses related to Liquid Propellant Rocket Engines (LPREs), and their graduate and undergraduate education programs are considered one of their most important contributions.

These design bureaus, or "konstruktorskoye buro" (KB) in Russian were state run organisations which were primarily responsible for carrying out research, development and prototyping of advanced technologies usually related to military hardware, such as turbojet engines, aircraft components, missiles, or space launch vehicles.

These organisations received relatively steady support and funding due to high military and spaceflight priorities, which facilitated the continuous development of new engine concepts and manufacturing methods.

Similarly, for the ambitious heavy N-l space launch vehicle intended for lunar and planetary missions, the Soviet Union developed and put into production at least two engines for each of the six stages.

These examples demonstrate the complex dynamics and challenges faced by the Soviet Union in managing the development and production of rocket engines through Design Bureaus.

The development of rocket engines in the Soviet Union was marked by significant achievements, but it also carried ethical considerations due to numerous accidents and fatalities.

Notably, the USSR holds the unfortunate distinction of having experienced more injuries and deaths resulting from liquid propellant rocket engine (LPRE) accidents than any other country.

The Soviet government, driven by the pursuit of scientific and technological superiority during the Cold War, sought to maintain an image of invincibility and conceal the failures that accompanied their advancements.

In addition, if the number of flights launched is low, there is a very high chance of a design, operations or manufacturing error causing destruction of the vehicle.

Due to their larger surface area, they are harder to cool and hence there is a need to run the combustion processes at much lower temperatures, losing efficiency.

Rockets that use common construction materials such as aluminium, steel, nickel or copper alloys must employ cooling systems to limit the temperatures that engine structures experience.

Assuming that the chemical potential energy of the propellants can be safely stored, the combustion process results in a great deal of heat being released.

A significant fraction of this heat is transferred to kinetic energy in the engine nozzle, propelling the rocket forward in combination with the mass of combustion products released.

Of these, only translation can do useful work to the vehicle, and while energy does transfer between modes this process occurs on a timescale far in excess of the time required for the exhaust to leave the nozzle.

Consequently, it is generally desirable for the exhaust species to be as simple as possible, with a diatomic molecule composed of light, abundant atoms such as H2 being ideal in practical terms.

Carbon-rich exhausts from kerosene-based fuels such as RP-1 are often orange in colour due to the black-body radiation of the unburnt particles, in addition to the blue Swan bands.

Jets from solid-propellant rockets can be highly visible, as the propellant frequently contains metals such as elemental aluminium which burns with an orange-white flame and adds energy to the combustion process.

Ninth Century Chinese Taoist alchemists discovered black powder in a search for the elixir of life; this accidental discovery led to fire arrows which were the first rocket engines to leave the ground.

[citation needed] A turning point in rocket technology emerged with a short manuscript entitled Liber Ignium ad Comburendos Hostes (abbreviated as The Book of Fires).

[8]: 247–266 During the late 1930s, German scientists, such as Wernher von Braun and Hellmuth Walter, investigated installing liquid-fuelled rockets in military aircraft (Heinkel He 112, He 111, He 176 and Messerschmitt Me 163).

The high specific impulse and low density of liquid hydrogen lowered the upper stage mass and the overall size and cost of the vehicle.

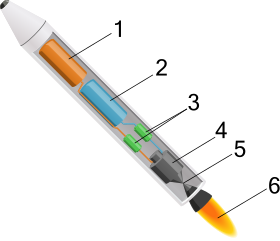

- Liquid fuel tank

- Liquid oxidiser tank

- Pumps feed fuel and oxidiser under high pressure.

- Combustion chamber mixes and burns the propellants.

- Exhaust nozzle expands and accelerates the gas jet to produce thrust.

- Exhaust exits nozzle.

- Solid fuel–oxidiser mixture (propellant) packed into casing

- Igniter initiates propellant combustion.

- Central hole in propellant acts as the combustion chamber .

- Exhaust nozzle expands and accelerates the gas jet to produce thrust.

- Exhaust exits nozzle.