Lakota religion

Lakota religionists believe that, due to their shared possession of wakʽą, humans exist in a state of kinship with all life forms, a relationship that informs adherents' behavior.

Prayers are given to the wakʽąpi to secure their assistance, often facilitated through the smoking of a sacred pipe or the provision of offerings, usually cotton flags or tobacco.

[22] Much of this adaptation is the result of visions experienced by its practitioners,[23] but also reflects influences absorbed, directly or indirectly, from neighboring Plains peoples as well as those from the Eastern Woodlands, Subarctic, and Great Basin.

"[32] The latter reflects the fact that many Lakota, like certain other Native Americans, prefer to describe their traditional beliefs and practices as "spirituality", largely as a reaction against the Christian missionary use of the term "religion".

[43] Displaying a holistic view of the universe,[44] Lakota religionists believe that wakʽą flows through the cosmos, animating all things,[34] and that all beings thus share the same essence.

[38] Both wakʽą itself, and the rituals that pertain to it, are considered to be wókʽokipʽe (dangerous),[48] with Stephen E. Feraca, a writer who worked at Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, relating that in Lakota religion, "fear and respect" were "virtually indistinguishable.

[63] Their appearance is thought to sometimes be marked by white or blue flashing lights,[67] but they can typically take any form and thus Lakota religionists believe they might encounter such entities in daily life without knowing it.

[90] Another Lakota tradition is that a wanáği who fails to enter the ghost world will wander aimlessly, where it can sometimes be seen materialized in human form or heard whistling and moaning.

[134] In the Lakota worldview, there are six directions, each with an associated color: west (black), north (red), east (yellow), south (white), the earth (green), and the sky (blue).

[137] At some point, it came to symbolise the idea of all nations living in harmony,[137] as well as the notion that all life is connected,[138] including humanity's relationship with the buffalo and the wider universe.

[106] Crawford noted that to "assure personal and communal health," it is important for Lakota traditionalists to honor their relatives, remain faithful to their bonds of kinship, and to affirm relationships with the cosmos and to wakʽą forces.

[153] DeMallie argued that ritual is more standardized than belief in Lakota religion and that the incorrect performance of a rite according to custom can be seen as invalidating it and potentially causing harm.

[163] It usually entails a ceremonial crying or wailing, followed by lifting the arms up with palms outstretched and then putting them towards the ground in a sign of respect and gratitude.

[168] These are not permanent spaces and ceremonial rules only apply for the duration of the ritual;[169] DeMallie noted that no "sharp distinction" is made between the sacred and the profane in Lakota tradition.

[176] The flags appear in different colors, each representing a cardinal direction: black (west), red (north), yellow (east), and white (south).

[195] Catlinite is quarried from near Pipestone, Minnesota; the Lakota term this iyanša (red stone), for in their mythology it formed from the blood of a people killed in a primordial flood.

[252] The modern sun dance is organized by a committee who select the date, pick a director, and arrange for publicity and the maintenance of the grounds east of Pine Ridge Village, where the ceremony takes place.

[259] While the decoration on the čhawákha varies, it typically features a red cloth banner and a brush bundle tied near the top,[178] the latter representing a nest of the thunderbirds,[260] as well as being an offering to secure the supply of wild plant foods.

[93] The Hunkapi lowanpi (Hunka ritual) is an adoption ceremony in which new kinship relations are established with somebody,[287] sometimes allowing the integration of non-Lakota people into Lakota families.

[289] Accounts from the early 20th century suggest that Lakota typically attributed all sickness to a supernatural causation, whether that be punishment from spirits or the curses of sorcerers.

[295] In the early 21st century it is nevertheless common for Lakota people to employ modern Western medicines alongside traditional healing methods or those of the Native American Church.

[95] Certain Lakota individuals provide a range of ritual services, including healing, counselling, locating missing persons or objects, predicting the future, directing ceremonies, and conjuring spirits.

The recounting of myths and songs, the repeated testimonials, the emphasis on the unity of the living, the departed dead, and the historical heroes, all forge stronger links between the participants in yuwipi ceremonies and help them glory in their differentiation from off-reservation culture.

[345] Scholar of religion Paul B. Steinmetz suggested that the yuwípi became the most common traditional rite among the Lakota during the reservation period due to an absence of alternatives.

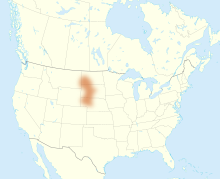

[362] Linguistic reconstruction places the homeland of the Lakota's ancestors, the proto-Western Siouans, to the west of Lake Michigan, an area encompassing southern Wisconsin, southeast Minnesota, northeast Iowa, and northern Illinois.

[371] From 1640, Europeans referred to the Oceti Šakowin as the Sioux, a term borrowed from the Ojibwe, in whose language it was a pejorative word meaning "lesser, or small, adder.

"[267] The "locus for contemporary religious revitalization" came from the Lakota communities of South Dakota, especially those on the reservations at Pine Ridge, Rosebud, Cheyenne River, and Standing Rock.

[405] Ritual leaders from these reservations subsequently stimulated revivals among other Sioux-speaking communities in North Dakota, Nebraska, Minnesota, Montana, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan.

Thus, they interpreted the sacred pipe as a foreshadowing of Jesus Christ, linked White Buffalo Woman with the Virgin Mary, and associated the sun dance tree with the Cross of the Crucifixion.

[419] In 2003, Arvol Looking Horse, the Keeper of the Buffalo Calf Pipe, issued a proclamation prohibiting non-Native entry to the hocoka spaces during the seven sacred rites.