Sitting Bull

After working as a performer with Buffalo Bill's Wild West show, Sitting Bull returned to the Standing Rock Agency in South Dakota.

Because of fears that Sitting Bull would use his influence to support the Ghost Dance movement, Indian Service agent James McLaughlin at Fort Yates ordered his arrest.

[20] From 1866 to 1868, Red Cloud, a leader of the Oglala Lakota, fought against U.S. forces, attacking their forts in an effort to keep control of the Powder River Country in present-day Montana.

He told the Jesuit missionary Pierre Jean De Smet, who sought him on behalf of the government: "I wish all to know that I do not propose to sell any part of my country.

"[28] The Panic of 1873 forced the Northern Pacific Railway's backers, such as Jay Cooke, into bankruptcy, which halted construction of the railroad through Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota territory.

[31] Although Sitting Bull did not attack Custer's expedition in 1874, the U.S. government was increasingly pressured by citizens to open the Black Hills to mining and settlement.

Failing in an attempt to negotiate a purchase or lease of the Hills, the government in Washington had to find a way around the promise to protect the Sioux in their land, as specified in the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie.

[33][34] Based on tribal oral histories, historian Margot Liberty theorizes that many Lakota bands allied with the Cheyenne during the Plains Wars because they thought the other nation was under attack by the U.S.

They needed the supplies at a time when white encroachment and the depletion of buffalo herds reduced their resources and challenged Native American independence.

Sitting Bull's refusal to adopt any dependence on the U.S. government meant that at times he and his small band of warriors lived isolated on the Plains.

When Native Americans were threatened by the United States, numerous members from various Sioux bands and other tribes, such as the Northern Cheyenne, came to Sitting Bull's camp.

After the ultimatum on January 1, 1876, when the U.S. Army began to track down as hostiles those Sioux and others living off the reservation, Native Americans gathered at Sitting Bull's camp.

Public shock and outrage at Custer's defeat and death, and the government's understanding of the military capability of the remaining Sioux, led the Department of War to assign thousands more soldiers to the area.

Due to the smaller size of the buffalo herds in Canada, Sitting Bull and his men found it difficult to find enough food to feed their starving people.

[44] Hunger and desperation eventually forced Sitting Bull and 186 of his family and followers to return to the United States and surrender on July 19, 1881.

Sitting Bull had his young son Crow Foot surrender his Winchester Rifle to major David H. Brotherton, commanding officer of Fort Buford.

Two weeks later, after waiting in vain for other members of his tribe to follow him from Canada, Sitting Bull and his band were transferred to Fort Yates, the military post located adjacent to the Standing Rock Agency.

Loaded onto a steamboat, the band of 172 people was sent down the Missouri River to Fort Randall near present-day Pickstown, South Dakota on the southern border of the state, where they spent the next 20 months.

"[47][48][49] In 1884, show promoter Alvaren Allen asked Agent James McLaughlin to allow Sitting Bull to tour parts of Canada and the northern United States.

[53] Historians have reported that Sitting Bull gave speeches about his desire for education for the young, and reconciling relations between the Sioux and whites.

[54] The historian Edward Lazarus wrote that Sitting Bull reportedly cursed his audience in Lakota in 1884, during an opening address celebrating the completion of the Northern Pacific Railway.

The translator, however, read the original address which had been written as a 'gracious act of amity', and the audience, including President Grant, was left none the wiser.

The tension between Sitting Bull and Agent McLaughlin increased, and each became warier of the other over several issues including division and sale of parts of the Great Sioux Reservation.

[59] During a time of harsh winters and long droughts impacting the Sioux Reservation, a Paiute Indian named Wovoka spread a religious movement from present-day Nevada east to the Plains that preached a resurrection of the Native.

[60] In 1890, James McLaughlin, the U.S. Indian agent at Fort Yates on Standing Rock Agency, feared that the Lakota leader was about to flee the reservation with the Ghost Dancers, so he ordered the police to arrest him.

The plan called for the arrest to take place at dawn on December 15 and advised the use of a light spring wagon to facilitate removal before his followers could rally.

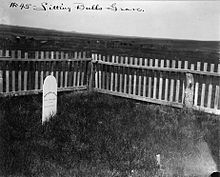

In 1953, Lakota family members exhumed what they believed to be Sitting Bull's remains, transporting them for reinterment near Mobridge, South Dakota, his birthplace.

[74] In August 2010, a research team led by Eske Willerslev, an ancient DNA expert at the University of Copenhagen, announced its intention to sequence the genome of Sitting Bull, with the approval of his descendants, using a hair sample obtained during his lifetime.

[76] Sitting Bull was the subject of, or a featured character in, several Hollywood motion pictures and documentaries, which have reflected changing ideas about him and Lakota culture in relation to the United States.

Among them are: As time passed, Sitting Bull has become a symbol and archetype of Native American resistance movements as well as a figure celebrated by descendants of his former enemies: