Land reform in Zimbabwe

[3] The United Nations has identified several key shortcomings with the contemporary programme, namely failure to compensate ousted landowners as called for by the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the poor handling of boundary disputes, and chronic shortages of material and personnel needed to carry out resettlement in an orderly manner.

[15] The foundation for the controversial land dispute in Zimbabwean society was laid at the beginning of European settlement of the region, which had long been the scene of mass movements by various Bantu peoples.

In the sixteenth century, Portuguese explorers had attempted to open up Zimbabwe for trading purposes, but the country was not permanently settled by European immigrants until three hundred years later.

Two hundred years later, Rozwi imperial rule began to crumble and the empire fell to the Karanga peoples, a relatively new tribe to the region which originated north of the Zambezi River.

[16] Both these peoples later came to form the nucleus of the Shona civilisation, along with the Zezuru in central Zimbabwe, the Korekore in the north, the Manyika in the east, the Ndau in the southeast, and the Kalanga in the southwest.

Population growth frequently resulted in the over-utilisation of the existing land, which became greatly diminished both in terms of cultivation and grazing due to the larger number of people attempting to share the same acreage.

[16] Land hunger was at the centre of the Rhodesian Bush War, and was addressed at Lancaster House, which sought to concede equitable redistribution to the landless without damaging the white farmers' vital contribution to Zimbabwe's economy.

[18] At independence from the United Kingdom in 1980, the Zimbabwean authorities were empowered to initiate the necessary reforms; as long as land was bought and sold on a willing basis, the British government would finance half the cost.

[18] In the late 1990s, Prime Minister Tony Blair terminated this arrangement when funds available from Margaret Thatcher's administration were exhausted, repudiating all commitments to land reform.

[19] This reflected a larger trend of permanent European settlement in the milder, drier regions of Southern Africa as opposed to the tropical and sub-tropical climates further north.

[20] In 1889 Cecil Rhodes and the British South Africa Company (BSAC) introduced the earliest white settlers to Zimbabwe as prospectors, seeking concessions from the Ndebele for mineral rights.

[21] An interim solution was the granting of land to the settlers in the hopes that they would develop productive farms and generate enough income to justify the colony's continued administrative costs.

[21] Exceptions were made during the Ndebele and Shona insurrections against the BSAC in the mid-1890s, when land was promised to any European men willing to take up arms in defence of the colony, irrespective of their financial status.

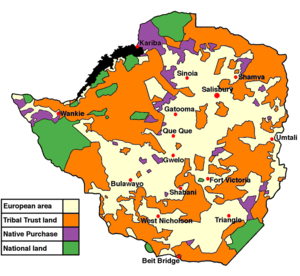

[24] This created two new problems: firstly, in the areas reserved for whites, the ratio of land to population was so high that many farms could not be exploited to their fullest potential, and some prime white-owned farmland was lying idle.

[21] The overcrowded conditions in the TTLs compelled large numbers of Shona and Ndebele alike to abandon their rural livelihoods and seek wage employment in the cities or on white commercial farms.

[24] Abuses of the system continued to abound; some white farmers took advantage of the legislation to shift their property boundaries into land formerly designated for black settlement, often without notifying the other landowners.

[24] Two years later, as part of the Internal Settlement, Zimbabwe Rhodesia's incoming biracial government under Bishop Abel Muzorewa abolished the reservation of land according to race.

[24] White farmers continued to own 73.8% of the most fertile land suited for intensive cash crop cultivation and livestock grazing, in addition to generating 80% of the country's total agricultural output.

[18][25] The British government, which mediated the talks, proposed a constitutional clause underscoring property ownership as an inalienable right to prevent a mass exodus of white farmers and the economic collapse of the country.

[31] Zimbabwe also began to court other donors through its Economic Structural Adjustment Policies (ESAP), which were projects implemented in concert with international agencies and tied to foreign loans.

[34] Prime Minister Mugabe, who assumed an executive presidency in 1987, had urged restraint by enforcing a leadership code of conduct which barred members of the ruling party, ZANU–PF, from monopolising large tracts of farmland and then renting them out for profit.

[37] Public opinion on the Zimbabwean land reform process among British citizens was decidedly mediocre; it was perceived as a poor investment on the part of the UK's government in an ineffectual and shoddily implemented programme.

[37] In June 1996, Lynda Chalker, British secretary of state for international development, declared that she could not endorse the new compulsory acquisition policy and urged Mugabe to return to the principles of "willing buyer, willing seller".

Notwithstanding the Lancaster House commitments, Short stated that her government was only prepared to support a programme of land reform that was part of a poverty eradication strategy.

[38][39] Kenneth Kaunda, former president of Zambia, responded dismissively by saying "when Tony Blair took over in 1997, I understand that some young lady in charge of colonial issues within that government simply dropped doing anything about it.

[34] Calls for accelerated land reform were also echoed by an affluent urban class of black Zimbabweans who were interested in making inroads into commercial farming, with public assistance.

– Patrick Chinamasa, Zimbabwe Finance Minister (2014)[41] The government held a referendum on the new constitution on 12–13 February 2000, despite having a sufficiently large majority in parliament to pass any amendment it wished.

[45] The violent takeover of Alamein Farm by retired Army General Solomon Mujuru sparked the first legal action against one of Robert Mugabe's inner circle.

[53] Parliament, dominated by ZANU–PF, passed a constitutional amendment, signed into law on 12 September 2005, that nationalised farmland acquired through the "Fast Track" process and deprived original landowners of the right to challenge in court the government's decision to expropriate their land.

[57] In January 2006, Agriculture Minister Joseph Made said Zimbabwe was considering legislation that would compel commercial banks to finance black peasants who had been allocated formerly white-owned farmland in the land reforms.