Devonian

Tetrapodomorphs, which include the ancestors of all four-limbed vertebrates (i.e. tetrapods), began diverging from freshwater lobe-finned fish as their more robust and muscled pectoral and pelvic fins gradually evolved into forelimbs and hindlimbs, though they were not fully established for life on land until the Late Carboniferous.

The Late Devonian extinction, which started about 375 Ma,[13] severely affected marine life, killing off most of the reef systems, most of the jawless fish, the placoderms, and nearly all trilobites save for a few species of the order Proetida.

The Great Devonian Controversy was a lengthy debate between Roderick Murchison, Adam Sedgwick and Henry De la Beche over the naming of the period.

Older literature on the Anglo-Welsh basin divides it into the Downtonian, Dittonian, Breconian, and Farlovian stages, the latter three of which are placed in the Devonian.

[21] The Devonian has also erroneously been characterised as a "greenhouse age", due to sampling bias: most of the early Devonian-age discoveries came from the strata of Western Europe and eastern North America, which at the time straddled the Equator as part of the supercontinent of Euramerica where fossil signatures of widespread reefs indicate tropical climates that were warm and moderately humid.

The first tetrapods appeared in the fossil record in the ensuing Famennian subdivision, the beginning and end of which are marked with extinction events.

Various smaller continents, microcontinents, and terranes were present east of Laurussia and north of Gondwana, corresponding to parts of Europe and Asia.

The Devonian Period was a time of great tectonic activity, as the major continents of Laurussia and Gondwana drew closer together.

The enormous "world ocean", Panthalassa, occupied much of the Northern Hemisphere as well as wide swathes east of Gondwana and west of Laurussia.

[29] Most of Laurussia was located south of the equator, but in the Devonian it moved northwards and began to rotate counterclockwise towards its modern position.

[31] For much of the Devonian, the majority of western Laurussia (North America) was covered by subtropical inland seas which hosted a diverse ecosystem of reefs and marine life.

Devonian reefs also extended along the southeast edge of Laurussia, a coastline now corresponding to southern England, Belgium, and other mid-latitude areas of Europe.

[29] In the Early and Middle Devonian, the west coast of Laurussia was a passive margin with broad coastal waters, deep silty embayments, river deltas and estuaries, found today in Idaho and Nevada.

In the Late Devonian, an approaching volcanic island arc reached the steep slope of the continental shelf and began to uplift deep water deposits.

[29][33] These collisions were associated with volcanic activity and plutons, but by the Late Devonian the tectonic situation had relaxed and much of South America was covered by shallow seas.

[29] The northern rim of Gondwana was mostly a passive margin, hosting extensive marine deposits in areas such as northwest Africa and Tibet.

Numerous mountain building events and granite and kimberlite intrusions affected areas equivalent to modern day eastern Australia, Tasmania, and Antarctica.

The eastern branch of the Paleo-Tethys was fully opened when South China and Annamia (a terrane equivalent to most of Indochina), together as a unified continent, detached from the northeastern sector of Gondwana.

Other Asian terranes remained attached to Gondwana, including Sibumasu (western Indochina), Tibet, and the rest of the Cimmerian blocks.

Although Siberia's margins were generally tectonically stable and ecologically productive, rifting and deep mantle plumes impacted the continent with flood basalts during the Late Devonian.

The last major round of volcanism, the Yakutsk Large Igneous Province, continued into the Carboniferous to produce extensive kimberlite deposits.

In the early Paleozoic, much of Europe was still attached to Gondwana, including the terranes of Iberia, Armorica (France), Palaeo-Adria (the western Mediterranean area), Bohemia, Franconia, and Saxothuringia.

This sequence of rifting and collision events led to the successive creation and destruction of several small seaways, including the Rheno-Hercynian, Saxo-Thuringian, and Galicia-Moldanubian oceans.

Marine faunas continued to be dominated by conodonts,[37] bryozoans,[38] diverse and abundant brachiopods,[39] the enigmatic hederellids,[40] microconchids,[38] and corals.

[44] Bactritoids make their first appearance in the Early Devonian as well; their radiation, along with that of ammonoids, has been attributed by some authors to increased environmental stress resulting from decreasing oxygen levels in the deeper parts of the water column.

[48] A now-dry barrier reef, located in present-day Kimberley Basin of northwest Australia, once extended 350 km (220 mi), fringing a Devonian continent.

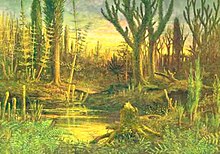

[58] The earliest land plants such as Cooksonia consisted of leafless, dichotomous axes with terminal sporangia and were generally very short-statured, and grew hardly more than a few centimetres tall.

[62] These tracheophytes were able to grow to large size on dry land because they had evolved the ability to biosynthesize lignin, which gave them physical rigidity and improved the effectiveness of their vascular system while giving them resistance to pathogens and herbivores.

The evolving co-dependence of insects and seed plants that characterized a recognizably modern world had its genesis in the Late Devonian Epoch.

[69] Amongst the severely affected marine groups were the brachiopods, trilobites, ammonites, and acritarchs, and the world saw the disappearance of an estimated 96% of vertebrates like conodonts and bony fishes, and all of the ostracoderms and placoderms.