Indus Valley Civilisation

[40][41] Although his original goal of demonstrating Harappa to be a lost Buddhist city mentioned in the seventh century CE travels of the Chinese visitor, Xuanzang, proved elusive,[41] Cunningham did publish his findings in 1875.

[42][43] Archaeological work in Harappa thereafter lagged until a new viceroy of India, Lord Curzon, pushed through the Ancient Monuments Preservation Act 1904, and appointed John Marshall to lead the ASI.

[47] By 1924, Marshall had become convinced of the significance of the finds, and on 24 September 1924, made a tentative but conspicuous public intimation in the Illustrated London News:[17] "Not often has it been given to archaeologists, as it was given to Schliemann at Tiryns and Mycenae, or to Stein in the deserts of Turkestan, to light upon the remains of a long forgotten civilisation.

"In the next issue, a week later, the British Assyriologist Archibald Sayce was able to point to very similar seals found in Bronze Age levels in Mesopotamia and Iran, giving the first strong indication of their date; confirmations from other archaeologists followed.

[v][53][54] By 2002, over 1,000 Mature Harappan cities and settlements had been reported, of which just under a hundred had been excavated,[f] mainly in the general region of the Indus and Ghaggar-Hakra rivers and their tributaries; however, there are only five major urban sites: Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, Dholavira, Ganeriwala and Rakhigarhi.

[56] After the partition, Mortimer Wheeler, the Director of ASI from 1944, oversaw the establishment of archaeological institutions in Pakistan, later joining a UNESCO effort tasked to conserve the site at Mohenjo-daro.

[58] Following a chance flash flood which exposed a portion of an archaeological site at the foot of the Bolan Pass in Balochistan, excavations were carried out in Mehrgarh by French archaeologist Jean-François Jarrige and his team in the early 1970s.

Lichtenstein,[105] the Mature Harappan civilisation was "a fusion of the Bagor, Hakra, and Kot Diji traditions or 'ethnic groups' in the Ghaggar-Hakra valley on the borders of India and Pakistan".

Eventually an agreement was reached, whereby the finds, totalling some 12,000 objects (most sherds of pottery), were split equally between the countries; in some cases this was taken very literally, with some necklaces and girdles having their beads separated into two piles.

Sir John Marshall reacted with surprise when he saw these two statuettes from Harappa:[128] When I first saw them I found it difficult to believe that they were prehistoric; they seemed to completely upset all established ideas about early art, and culture.

[143] During 4300–3200 BCE of the chalcolithic period (copper age), the Indus Valley Civilisation area shows ceramic similarities with southern Turkmenistan and northern Iran which suggest considerable mobility and trade.

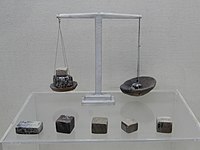

[144] Judging from the dispersal of Indus civilisation artefacts, the trade networks economically integrated a huge area, including portions of Afghanistan, the coastal regions of Persia connected by the Gulf of Oman from the Arabian Sea, northern and western India, and Mesopotamia, leading to the development of Indus-Mesopotamia relations.

[145] Ancient DNA studies of graves at Bronze Age sites at Gonur Depe, Turkmenistan, and Shahr-e Sukhteh, Iran, have identified 11 individuals of South Asian descent, who are presumed to be of mature Indus Valley origin.

Figure 7.16 Mohenjo-daro: representation of ship on terracotta amulet (length 4.5 cm) after Dales)Daniel T. Potts writes: It is generally assumed that most trade between the Indus Valley (ancient Meluhha?)

Although there is no incontrovertible proof that this was indeed the case, the distribution of Indus-type artifacts on the Oman peninsula, on Bahrain and in southern Mesopotamia makes it plausible that a series of maritime stages linked the Indus Valley and the Gulf region.

[148][150][151] Dennys Frenez recently regards that: Indus-type and Indus-related artifacts were found over a large and differentiated ecumene, encompassing Central Asia, the Iranian Plateau, Mesopotamia and the northern Levant, the Persian Gulf, and the Oman Peninsula.

[156][75][ad] Research by J. Bates et al. (2016) confirms that Indus populations were the earliest people to use complex multi-cropping strategies across both seasons, growing foods during summer (rice, millets and beans) and winter (wheat, barley and pulses), which required different watering regimes.

[157] Bates et al. (2016) also found evidence for an entirely separate domestication process of rice in ancient South Asia, based around the wild species Oryza nivara.

However, due to the sparsity of evidence, which is open to varying interpretations, and the fact that the Indus script remains undeciphered, the conclusions are partly speculative and largely based on a retrospective view from a much later Hindu perspective.

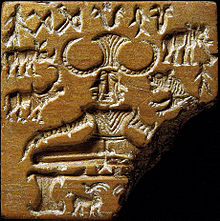

[184] Early and influential work in the area that set the trend for Hindu interpretations of archaeological evidence from the Harappan sites[185] was that of John Marshall, who in 1931 identified the following as prominent features of the Indus religion: a Great Male God and a Mother Goddess; deification or veneration of animals and plants; a symbolic representation of the phallus (linga) and vulva (yoni); and, use of baths and water in religious practice.

Marshall identified the figure as an early form of the Hindu god Shiva (or Rudra), who is associated with asceticism, yoga, and linga; regarded as a lord of animals, and often depicted as having three eyes.

However the function of the female figurines in the life of Indus Valley people remains unclear, and Possehl does not regard the evidence for Marshall's hypothesis to be "terribly robust".

[198] In contrast to contemporary Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilisations, Indus Valley lacks any monumental palaces, even though excavated cities indicate that the society possessed the requisite engineering knowledge.

Several sites have been proposed by Marshall and later scholars as possibly devoted to religious purposes, but at present only the Great Bath at Mohenjo-daro is widely thought to have been so used, as a place for ritual purification.

[196][201] The funerary practices of the Harappan civilisation are marked by fractional burial (in which the body is reduced to skeletal remains by exposure to the elements before final interment), and even cremation.

Examination of human skeletons from the site of Harappa in the 2010s demonstrated that the end of the Indus civilisation saw an increase in inter-personal violence and in infectious diseases like leprosy and tuberculosis.

Stone sculptures were deliberately vandalised, valuables were sometimes concealed in hoards, suggesting unrest, and the corpses of animals and even humans were left unburied in the streets and in abandoned buildings.

[215] However, there is greater continuity and overlap between Late Harappan and subsequent cultural phases at sites in Punjab, Haryana, and western Uttar Pradesh, primarily small rural settlements.

[224] The climate change which caused the collapse of the Indus Valley Civilisation was possibly due to "an abrupt and critical mega-drought and cooling 4,200 years ago", which marks the onset of the Meghalayan Age, the present stage of the Holocene.

[4] The Indian monsoon declined and aridity increased, with the Ghaggar-Hakra retracting its reach towards the foothills of the Himalaya,[4][228][229] leading to erratic and less extensive floods that made inundation agriculture less sustainable.