Latin American Boom

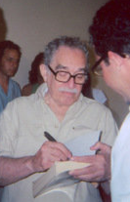

The Boom is most closely associated with Julio Cortázar of Argentina, Carlos Fuentes of Mexico, Mario Vargas Llosa of Peru, and Gabriel García Márquez of Colombia.

For example, on September 11, 1973, the democratically elected President Salvador Allende was overthrown in Chile and replaced by General Augusto Pinochet, who went on to rule until the end of the 1980s.

[12] Fernando Alegria considers Augusto Roa Bastos' Hijo de hombre the inaugural work of the Boom even though, as Shaw notes, it was published in 1959.

"[16] The greater attention paid to Latin American novelists and their international success in the 1960s, a phenomenon that was called the Boom, affected all writers and readers in that period.

The period of euphoria can be considered closed when in 1971 the Cuban government hardened its party line and the poet Heberto Padilla was forced to reject in a public document his so-called decadent and deviant views.

[18] Elizabeth Coonrod Martinez argues that the writers of the Vanguardia were the "true precursors" to the Boom, writing innovative and challenging novels before Borges and others conventionally thought to be the main Latin American inspirations for the mid-20th century movement.

In general—and considering there are many countries and hundreds of important authors—at the start of the period, Realism prevails, with novels tinged by an existentialist pessimism, with well-rounded characters lamenting their destinies, and a straightforward narrative line.

In the 1960s, language loosens up, gets hip, pop, streetwise, characters are much more complex, and the chronology becomes intricate, making of the reader an active participant in the deciphering of the text.

They treat time as nonlinear, often use more than one perspective or narrative voice and feature a great number of neologisms (the coining of new words or phrases), puns and even profanities.

As Pope writes, in reference to the style of the Boom: "It relied on a Cubist superposition of different points of view, it made time and lineal progress questionable, and it was technically complex.

"[22] Other notable characteristics of the Boom include the treatment of both "rural and urban settings", internationalism, an emphasis on both the historical and the political, as well as "questioning of regional as well as, or more than, national identity; awareness of hemisphereic as well as worldwide economic and ideological issues; polemicism; and timeliness.

Of the Boom writers, Gabriel García Márquez is most closely associated with the use of magical realism; indeed, he is credited with bringing it "into vogue" after the publishing of One Hundred Years of Solitude in 1967.

Plots, while often based on real experiences, incorporate strange, fantastic, and legendary elements, mythical peoples, speculative settings, and characters who, while plausible, could also be unreal, and combine the true, the imaginary, and the nonexistent in such a way that they are difficult to separate.

An example is Roa Bastos's I, the Supreme, which depicts the 19th-century Paraguayan dictatorship of José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia but was published at the height of Alfredo Stroessner's regime.

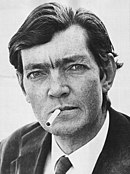

While the names of many other writers may be added to the list, the following may not be omitted: Julio Cortázar was born in Belgium in 1914 to Argentinian parents with whom he lived in Switzerland until moving to Buenos Aires at the age of four.

[29] Like other Boom writers, Cortázar grew to question the politics in his country: his public opposition to Juan Perón caused him to leave his professorial position at the University of Mendoza and, ultimately, led to his exile.

In 1955 Fuentes and Emmanuel Carballo founded the journal Revista Mexicana de Literatura which introduced Latin Americans to the works of European Modernists and the ideas of Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus.

Vargas Llosa also wrote The Green House (1966), the epic Conversation in The Cathedral (1969), Captain Pantoja and the Special Service (1973), and post-Boom novels such as Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter (1977).

Juan Rulfo, the author of two books, only one of them a novel, was the acknowledged master incorporated a posteriori; a writer who balances social concern, verbal experimentation and unique style.

Examples are Jorge Amado (although he began writing novels back in the 1930s) of Brazil, Salvador Garmendia of Venezuela, Gastón Suárez and Marcelo Quiroga Santa Cruz of Bolivia and David Viñas of Argentina, among many others.

However, as Alejandro Herrero-Olaizola notes, the revenue generated by the publishing of these novels gave a boost to the Spanish economy, even as the works were subjected to Franco's censors.

[46] Some of the Seix Barral-published novels include Mario Vargas Llosa's The Time of the Hero (1963) and his Captain Pantoja and the Special Service (1973), and Manuel Puig's Betrayed by Rita Hayworth (1971).

[52] Authors such as Severo Sarduy, who was associated with the French intellectuals of Tel Quel, have critiqued the tropes (e.g., phallogocentric discourse) that supported much of the literary movement’s legitimacy.

A testimony to the Boom's global impact is the fact that "up-and-coming international writers" look upon the likes of Fuentes, García Márquez or Vargas Llosa as their mentors.

His novel The Obscene Bird of Night (El obsceno pájaro de la noche, 1970) is considered, as Philip Swanson notes, "one of the classics of the Boom.

The post-Boom is distinct from the Boom in various respects, most notably in the presence of female authors such as Isabel Allende (The House of the Spirits, 1982), Luisa Valenzuela (The Lizard's Tales, 1983), Giannina Braschi (Empire of Dreams, 1988; Yo-Yo Boing!, 1998), Cristina Peri Rossi (Ship of Fools, 1984) and Elena Poniatowska (Tinisima, 1991).

"[62] Shaw identifies Antonio Skármeta (Ardiente paciencia, 1985), Rosario Ferré ("La muñeca menor", 1976; The House on the Lagoon, 1999) and Gustavo Sainz (The Princess of the Iron Palace, 1974; A troche y moche, 2002) as Post-Boom writers.