History of Latin America

Before the arrival of Europeans in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, the region was home to many indigenous peoples, including advanced civilizations, most notably from South: the Olmec, Maya, Muisca, Aztecs and Inca.

Colonial-era religion played a crucial role in everyday life, with the Spanish Crown ensuring religious purity and aggressively prosecuting perceived deviations like witchcraft.

"[1] The idea was later taken up by Latin American intellectuals and political leaders of the mid- and late-nineteenth century, who no longer looked to Spain or Portugal as cultural models, but rather to France.

Although the region now known as Latin America stretches from northern Mexico to Tierra del Fuego, the diversity of its geography, topography, climate, and cultivable land means that populations were not evenly distributed.

Agricultural surpluses from intensive cultivation of maize in Mesoamerica and potatoes and hardy grains in the Andes were able to support distant populations beyond farmers' households and communities.

Surpluses allowed the creation of social, political, religious, and military hierarchies, urbanization with stable village settlements and major cities, specialization of craft work, and the transfer of products via tribute and trade.

The Portuguese built their empire in Brazil, which fell in their sphere of influence owing to the Treaty of Tordesillas, by developing the land for sugar production since there was a lack of a large, complex society or mineral resources.

The size of the indigenous populations has been studied in the modern era by historians,[9][10][11] but Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas raised the alarm in the earliest days of Spanish settlement in the Caribbean in his A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies.

Francisca de Figueroa, an African-Iberian woman seeking entrance into the Americas, petitioned the Spanish Crown in 1600 in order to gain a license to sail to Cartagena.

I order you to allow passage to the Province of Cartagena for Francisca de Figueroa ..."[16] This example points to the importance of religion, when attempting to travel to the Americas during colonial times.

Paula de Eguiluz was a woman of African descent who was born in Santo Domingo and grew up as a slave, sometime in her youth she learned the trade of witches and was publicly known to be a sorceress.

Independence also created a new, self-consciously "Latin American" ruling class and intelligentsia, which at times avoided Spanish and Portuguese models in their quest to reshape their societies.

The political landscape was occupied by conservatives, who believed that the preservation of the old social hierarchies served as the best guarantee of national stability and prosperity, and liberals, who sought to bring about progress by freeing up the economy and individual initiative.

[21][22] Indeed, in Chile the war bought an end to a period of scientific and cultural influence writer Eduardo de la Barra scorningly called "the German bewichment" (Spanish: el embrujamiento alemán).

Following the 1922 Latin American Games in Rio de Janeiro, the IOC helped to establish national Olympic committees and prepare for future competition.

The policies of import substitution industrialization adopted in Latin America when exports slowed due to the Great Depression and subsequent isolation in World War II were now subject to international competition.

In Chile, Salvador Allende and a coalition of leftists, Unidad Popular, won an electoral victory in 1970 and lasted until the violent military coup of 11 September 1973.

The U.S. was concerned with the spread of communism in Latin America, and U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower responded to the threat he saw in the Dominican Republic's dictator Rafael Trujillo, who voiced a desire to seek an alliance with the Soviet Union.

[38] U.S. President John F. Kennedy initiated the Alliance for Progress in 1961, to establish economic cooperation between the U.S. and Latin America and provide $20 billion for reform and counterinsurgency measures.

Although the initial overthrow of the Somoza regime in 1978–79 was a bloody affair, the Contra War of the 1980s took the lives of tens of thousands of Nicaraguans and was the subject of fierce international debate.

Pope Paul VI actively implemented reforms and sought to align the Catholic Church on the side of the dispossessed, ("preferential option for the poor"), rather than remain a bulwark of conservative elites and right-wing repressive regimes.

Despite the Vatican stance against liberation theology, articulated in 1984 by Cardinal Josef Ratzinger, later Pope Benedict XVI, many Catholic clergy and laity worked against repressive military regimes.

After a military coup ousted the democratically elected Salvador Allende, the Chilean Catholic Church was a force in opposition to the regime of Augusto Pinochet and for human rights.

The term has become associated with neoliberal policies in general and drawn into the broader debate over the expanding role of the free market, constraints upon the state, and US influence on other countries' national sovereignty.

A "reversal of development" reigned over Latin America, seen through negative economic growth, declines in industrial production, and thus, falling living standards for the middle and lower classes.

Significantly, democratic governments began replacing military regimes across much of Latin America and the realm of the state became more inclusive (a trend that proved conducive to social movements), but economic ventures remained exclusive to a few elite groups within society.

Neoliberal restructuring consistently redistributed income upward, while denying political responsibility to provide social welfare rights, and development projects throughout the region increased both inequality and poverty.

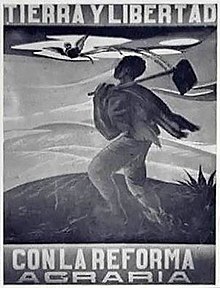

Rural movements made demands related to unequal land distribution, displacement at the hands of development projects and dams, environmental and Indigenous concerns, neoliberal agricultural restructuring, and insufficient means of livelihood.

Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff in Brazil, Fernando Lugo in Paraguay, Néstor and Cristina Kirchner in Argentina, Tabaré Vázquez and José Mujica in Uruguay, the Lagos and Bachelet governments in Chile, Evo Morales in Bolivia, Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua, Manuel Zelaya in Honduras (although deposed by the 28 June 2009 coup d'état), and Rafael Correa of Ecuador are all part of this wave of left-wing politicians, who also often declare themselves socialists, Latin Americanists or anti-imperialists.

[52] A resurgence of the rise of left-wing political parties in Latin America by their electoral victories, however, was initiated by Mexico in 2018 and Argentina in 2019, and further strengthened by Bolivia in 2020 along with Peru, Honduras and Chile in 2021 and Colombia and Brazil in 2022.