Latin Church

The "Latin Rite" is the whole of the patrimony of that distinct particular church, by which it manifests its own manner of living the faith, including its own liturgy, its theology, its spiritual practices and traditions and its canon law.

This scheme, tacitly at least accepted by Rome, is constructed from the viewpoint of Greek Christianity and does not take into consideration other churches of great antiquity which developed in the East outside the frontiers of the Roman Empire.

[32] In the Latin Church, the norm for administration of confirmation is that, except when in danger of death, the person to be confirmed should "have the use of reason, be suitably instructed, properly disposed, and able to renew the baptismal promises",[33] and "the administration of the Most Holy Eucharist to children requires that they have sufficient knowledge and careful preparation so that they understand the mystery of Christ according to their capacity and are able to receive the body of Christ with faith and devotion.

[40] Believing that the grace of Christ was indispensable to human freedom, he helped formulate the doctrine of original sin and made seminal contributions to the development of just war theory.

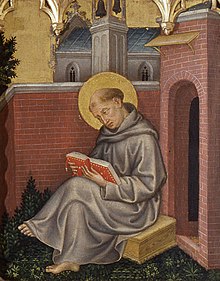

In both his philosophical and theological reasoning, Augustine was greatly influenced by Stoicism, Platonism and Neoplatonism, particularly by the work of Plotinus, author of the Enneads, probably through the mediation of Porphyry and Victorinus (as Pierre Hadot has argued).

"[63] Universities developed in the large cities of Europe during this period, and rival clerical orders within the church began to battle for political and intellectual control over these centers of educational life.

Later, the Eastern Orthodox ascetic and archbishop of Thessaloniki, (Saint) Gregory Palamas argued in defense of hesychast spirituality, the uncreated character of the light of the Transfiguration, and the distinction between God's essence and energies.

Historically Latin Christianity has tended to reject Palamism, especially the essence-energies distinction, some times characterizing it as a heretical introduction of an unacceptable division in the Trinity and suggestive of polytheism.

It has formulated this doctrine by reference to biblical verses that speak of purifying fire (1 Corinthians 3:15 and 1 Peter 1:7) and to the mention by Jesus of forgiveness in the age to come (Matthew 12:32).

In contrast, the celestial Hades was understood as an intermediary place where souls spent an undetermined time after death before either moving on to a higher level of existence or being reincarnated back on earth.

Pope Gregory the Great's Dialogues, written in the late 6th century, evidence a development in the understanding of the afterlife distinctive of the direction that Latin Christendom would take: As for certain lesser faults, we must believe that, before the Final Judgment, there is a purifying fire.

Paul J. Griffiths notes: "Recent Catholic thought on purgatory typically preserves the essentials of the basic doctrine while also offering second-hand speculative interpretations of these elements.

"[122] Thus Joseph Ratzinger wrote: "Purgatory is not, as Tertullian thought, some kind of supra-worldly concentration camp where man is forced to undergo punishment in a more or less arbitrary fashion.

"[123] In Theological Studies, John E. Thiel argued that "purgatory virtually disappeared from Catholic belief and practice since Vatican II" because it has been based on "a competitive spirituality, gravitating around the religious vocation of ascetics from the late Middle Ages".

The representatives of the Eastern Orthodox Church at the Council of Florence argued against these notions, while declaring that they do hold that there is a cleansing after death of the souls of the saved and that these are assisted by the prayers of the living: "If souls depart from this life in faith and charity but marked with some defilements, whether unrepented minor ones or major ones repented of but without having yet borne the fruits of repentance, we believe that within reason they are purified of those faults, but not by some purifying fire and particular punishments in some place.

[155] The theological underpinnings of Immaculate Conception had been the subject of debate during the Middle Ages with opposition provided by figures such as Saint Thomas Aquinas, a Dominican.

[158][159][160][161] The Blessed John Duns Scotus (d. 1308), a Friar Minor like Saint Bonaventure, argued, that from a rational point of view it was certainly as little derogatory to the merits of Christ to assert that Mary was by him preserved from all taint of sin, as to say that she first contracted it and then was delivered.

"[164] The complete defined dogma of the Immaculate Conception states: We declare, pronounce, and define that the doctrine which holds that the most Blessed Virgin Mary, in the first instance of her conception, by a singular grace and privilege granted by Almighty God, in view of the merits of Jesus Christ, the Saviour of the human race, was preserved free from all stain of original sin, is a doctrine revealed by God and therefore to be believed firmly and constantly by all the faithful.

[165] Declaramus, pronuntiamus et definimus doctrinam, quae tenet, beatissimam Virginem Mariam in primo instanti suae Conceptionis fuisse singulari omnipotentis Dei gratia et privilegio, intuitu meritorum Christi lesu Salvatoris humani generis, ab omni originalis culpae labe praeservatam immunem, esse a Deo revelatam, atque idcirco ab omnibus fidelibus firmiter constanterque credendam.

On 1 November 1950, in the Apostolic Constitution Munificentissimus Deus, Pope Pius XII declared the Assumption of Mary as a dogma: By the authority of our Lord Jesus Christ, of the Blessed Apostles Peter and Paul, and by our own authority, we pronounce, declare, and define it to be a divinely revealed dogma: that the Immaculate Mother of God, the ever Virgin Mary, having completed the course of her earthly life, was assumed body and soul into heavenly glory.

[168]In Pius XII's dogmatic statement, the phrase "having completed the course of her earthly life", leaves open the question of whether the Virgin Mary died before her assumption or not.

[169] Ludwig Ott writes in his book Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma that "the fact of her death is almost generally accepted by the Fathers and Theologians, and is expressly affirmed in the Liturgy of the Church", to which he adds a number of helpful citations.

The dogmatic definition within the Apostolic Constitution Munificentissimus Deus which, according to Roman Catholic dogma, infallibly proclaims the doctrine of the Assumption leaves open the question of whether, in connection with her departure, Mary underwent bodily death.

Orthodox tradition is clear and unwavering in regard to the central point [of the Dormition]: the Holy Virgin underwent, as did her Son, a physical death, but her body—like His—was afterwards raised from the dead and she was taken up into heaven, in her body as well as in her soul.

That does not mean, however, that she is dissociated from the rest of humanity and placed in a wholly different category: for we all hope to share one day in that same glory of the Resurrection of the Body which she enjoys even now.

In an early Venetian school Coronation of the Virgin by Giovanni d'Alemagna and Antonio Vivarini, (c. 1443), God the Father is shown in the representation consistently used by other artists later, namely as a patriarch, with benign, yet powerful countenance and with long white hair and a beard, a depiction largely derived from, and justified by, the description of the Ancient of Days in the Old Testament, the nearest approach to a physical description of God in the Old Testament:[178]... the Ancient of Days did sit, whose garment was white as snow, and the hair of his head like the pure wool: his throne was like the fiery flame, and his wheels as burning fire.

(Daniel 7:9) St Thomas Aquinas recalls that some bring forward the objection that the Ancient of Days matches the person of the Father, without necessarily agreeing with this statement himself.

[179] By the twelfth century depictions of a figure of God the Father, essentially based on the Ancient of Days in the Book of Daniel, had started to appear in French manuscripts and in stained glass church windows in England.

[185] From the 1990s, the issue of sexual abuse of minors by Western Catholic clergy and other church members has become the subject of civil litigation, criminal prosecution, media coverage and public debate in countries around the world.

The Western Catholic Church has been criticised for its handling of abuse complaints when it became known that some bishops had shielded accused priests, transferring them to other pastoral assignments where some continued to commit sexual offences.