Law of sines

The law of sines can be generalized to higher dimensions on surfaces with constant curvature.

[1] The equivalent of the law of sines, that the sides of a triangle are proportional to the chords of double the opposite angles, was known to the 2nd century Hellenistic astronomer Ptolemy and used occasionally in his Almagest.

[2] Statements related to the law of sines appear in the astronomical and trigonometric work of 7th century Indian mathematician Brahmagupta.

In his Brāhmasphuṭasiddhānta, Brahmagupta expresses the circumradius of a triangle as the product of two sides divided by twice the altitude; the law of sines can be derived by alternately expressing the altitude as the sine of one or the other base angle times its opposite side, then equating the two resulting variants.

[3] An equation even closer to the modern law of sines appears in Brahmagupta's Khaṇḍakhādyaka, in a method for finding the distance between the Earth and a planet following an epicycle; however, Brahmagupta never treated the law of sines as an independent subject or used it more systematically for solving triangles.

[4] The spherical law of sines is sometimes credited to 10th century scholars Abu-Mahmud Khujandi or Abū al-Wafāʾ (it appears in his Almagest), but it is given prominence in Abū Naṣr Manṣūr's Treatise on the Determination of Spherical Arcs, and was credited to Abū Naṣr Manṣūr by his student al-Bīrūnī in his Keys to Astronomy.

[5] Ibn Muʿādh al-Jayyānī's 11th-century Book of Unknown Arcs of a Sphere also contains the spherical law of sines.

The 13th-century Persian mathematician Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī stated and proved the planar law of sines: In any plane triangle, the ratio of the sides is equal to the ratio of the sines of the angles opposite to those sides.

That is, in triangle ABC, we have AB : AC = Sin(∠ACB) : Sin(∠ABC) By employing the law of sines, al-Tusi could solve triangles where either two angles and a side were known or two sides and an angle opposite one of them were given.

When three sides were given, he dropped a perpendicular line and then used Proposition II-13 of Euclid's Elements (a geometric version of the law of cosines).

Given a general triangle, the following conditions would need to be fulfilled for the case to be ambiguous: If all the above conditions are true, then each of angles β and β′ produces a valid triangle, meaning that both of the following are true:

the common value of the three fractions is actually the diameter of the triangle's circumcircle.

lie on the same circle and subtend the same chord c; thus, by the inscribed angle theorem,

The second equality above readily simplifies to Heron's formula for the area.

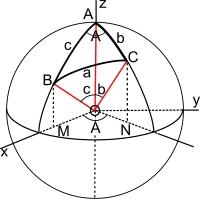

The spherical law of sines deals with triangles on a sphere, whose sides are arcs of great circles.

The arc BC subtends an angle of magnitude a at the centre.

The vector OC projects to ON in the xy-plane and the angle between ON and the x-axis is A.

The scalar triple product, OA ⋅ (OB × OC) is the volume of the parallelepiped formed by the position vectors of the vertices of the spherical triangle OA, OB and OC.

This volume is invariant to the specific coordinate system used to represent OA, OB and OC.

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\bigl (}\mathbf {OA} \cdot (\mathbf {OB} \times \mathbf {OC} ){\bigr )}^{2}&=\left(\det {\begin{pmatrix}\mathbf {OA} &\mathbf {OB} &\mathbf {OC} \end{pmatrix}}\right)^{2}\\[4pt]&={\begin{vmatrix}0&0&1\\\sin c&0&\cos c\\\sin b\cos A&\sin b\sin A&\cos b\end{vmatrix}}^{2}=\left(\sin b\sin c\sin A\right)^{2}.\end{aligned}}}

where V is the volume of the parallelepiped formed by the position vector of the vertices of the spherical triangle.

By applying similar reasoning, we obtain the spherical law of sine:

A purely algebraic proof can be constructed from the spherical law of cosines.

The figure used in the Geometric proof above is used by and also provided in Banerjee[13] (see Figure 3 in this paper) to derive the sine law using elementary linear algebra and projection matrices.

which is the analog of the formula in Euclidean geometry expressing the sine of an angle as the opposite side divided by the hypotenuse.

Define a generalized sine function, depending also on a real parameter

, that is, the Euclidean, spherical, and hyperbolic cases of the law of sines described above.

The absolute value of the polar sine (psin) of the normal vectors to the three facets that share a vertex of the tetrahedron, divided by the area of the fourth facet will not depend upon the choice of the vertex:[15]

More generally, for an n-dimensional simplex (i.e., triangle (n = 2), tetrahedron (n = 3), pentatope (n = 4), etc.)

Writing V for the hypervolume of the n-dimensional simplex and P for the product of the hyperareas of its (n − 1)-dimensional facets, the common ratio is