Le Chahut

Formerly in the collection of French Symbolist poet and art critic Gustave Kahn, Chahut is located at the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, Netherlands.

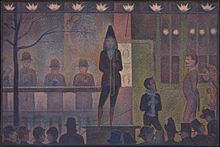

The background consists of ornate cabaret-style lighting fixtures, and a few members of the audience sitting in the front row, their eyes fixed on the performance.

On the lower right another client is staring with a sidelong glance, indicative of sexual desire or sly and malicious intent; the archetype of a male voyeur, often portrayed in mid-century journalistic illustrations of the can-can.

[3] Chahut (literally meaning noise or uproar) is an alternative name for the can-can, a provocative, sexually charged dance that first appeared in the ballrooms of Paris around 1830.

[3] The anti-naturalist tone of Chahut, with its primacy of expression over appearance and its eloquent use of lines and color, reflects the influence of both Charles Blanc and Humbert de Superville.

Its forms are not abstract, but schematic and perfectly recognizable as the popular social milieu within which Seurat had been plunged since his move to Montmartre in 1886; with its sexually provocative subject matter (revealing legs and undergarments) inspired by burlesque dancing of Montmartre performers, café-concerts, theaters, ballrooms, music halls, vaudevilles, and fashionable Parisian nightlife.

[3] Jules Christophe, Seurat's friend who interviewed him for a short biography published in spring 1890, described Le Chahut as the end of a fanciful quadrille on the stage of a Montmartre cafe-concert: a spectator, half show-off, half randy investigator, who smells, one might say, with an eminently uplifted nose; an orchestra leader with hieratic gesture, seen from the back; some hands on a flute; and, with partners having serpentine suit tails, two young dancers in evening dress, skirts flying up, thin legs distinctly elevatory, with laughs on upraised lips, and provocative noses.

[3]Chahut was exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants, 20 March–27 April 1890,[6] eclipsing his other large entry: Jeune femme se poudrant (Young Woman Powdering Herself), to which critics at the time paid little attention.

His works are "exemplary specimens of a highly developed decorative art, which sacrifices the anecdote to the arabesque, nomenclature to synthesis, the fugitive to the permanent, and confers on nature—weary at last of its precarious reality—an authentic reality," wrote Fénéon[4]By 1904 Neo-Impressionism had evolved considerably, in a move away from nature, away from imitation, toward the distillation of essential geometric shapes and harmonious movements.

Cross, Paul Signac, along with Henri Matisse, Jean Metzinger, Robert Delaunay, André Derain (of the younger generation) now painted with large brushstrokes that could never blend in the eye of the observer.

Pure bold colors (reds, blues, yellows, greens and magentas) bounced off the manifold of their canvas, "making them as free of the trammels of nature", writes Herbert, "as any painting then being done in Europe.

[1][7] Seurat had been the founder of Neo-Impressionism, its most innovative and fervent protagonist, and proved to be one of the most influential in the eyes of the emerging avant-garde; many of whom—such as Jean Metzinger, Robert Delaunay, Gino Severini and Piet Mondrian—transited through a Neo-Impressionist phase, prior to their Fauve, Cubist or Futurist endeavors.