Divisionism

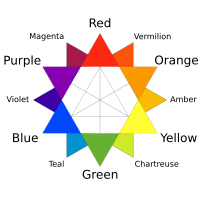

Divisionism, also called chromoluminarism, is the characteristic style in Neo-Impressionist painting defined by the separation of colors into individual dots or patches that interact optically.

Georges Seurat founded the style around 1884 as chromoluminarism, drawing from his understanding of the scientific theories of Michel Eugène Chevreul, Ogden Rood and Charles Blanc, among others.

[4][7] Impressionism originated in France in the 1870s, and is characterized by the use of quick, short, broken brushstrokes to accurately capture the momentary effects of light and atmosphere in an outdoor scene.

In fact, Signac's book, D’Eugène Delacroix au Néo-Impressionnisme, published in 1899, coined the term Divisionism and became widely recognized as the manifesto of Neo-Impressionism.

[13] Additionally, through Paul Signac's advocacy of Divisionism, an influence can be seen in some of the works of Vincent van Gogh, Henri Matisse, Jean Metzinger, Robert Delaunay and Pablo Picasso.

Spearheaded by Grubicy de Dragon, and codified later by Gaetano Previati in his Principi scientifici del divisionismo of 1906, a number of painters mainly in Northern Italy experimented to various degrees with these techniques.

[17] It was, however, in the subject of landscapes that divisionism found strong advocates, including Giovanni Segantini, Gaetano Previati, Angelo Morbelli and Matteo Olivero.

Further adherents in painting genre subjects were Plinio Nomellini, Rubaldo Merello, Giuseppe Cominetti, Camillo Innocenti, Enrico Lionne and Arturo Noci.

Divisionism was also in important influence in the work of Futurists Gino Severini (Souvenirs de Voyage, 1911); Giacomo Balla (Arc Lamp, 1909);[18] Carlo Carrà (Leaving the scene, 1910); and Umberto Boccioni (The City Rises, 1910).

[1][19][20] Divisionism quickly received both negative and positive attention from art critics, who generally either embraced or condemned the incorporation of scientific theories in the Neo-Impressionist techniques.