Le Quart Livre

[5] The circumstances surrounding the publication of Le Quart Livre in 1552 were more propitious, with Rabelais overseeing the printing of his book and receiving direct support from Odet de Coligny and King Henry II.

The woodcutter, in his distress, was so vocal in his lamentations that his pleas reached Jupiter, who was otherwise engaged in addressing matters of international politics with the other deities of Olympus, including the ongoing conflict between Moscow and the Tartars.

Some commentators view it as an example of Alexandrian symbolism, while others see it as an illustration of a pre-classical taste for idealized imitation or even as a device employed by the author to engage in self-referential discourse within the context of the fiction.

The Hebrew term cheli, which appears in the Bible and is used to refer to "pots and pans", suggests that a Kabbalistic motif may underlie the text, potentially related to the vessels of the Chevirat haKelim [fr] and the celestial hierarchy.

[22] In response, Panurge recounts the method of Lord Basché, who, during his struggle against the troops of Julius II and harassed by the prior of Saint-Louand during the War of the League of Cambrai, organized a fictitious betrothal, during which a custom requires friendly blows.

[25] A series of unusual deaths is referenced in this passage, including that of Aeschylus, who is said to have perished from a tortoiseshell dropped by an eagle; a man who was ashamed to release gas in front of Emperor Claudius; and Philomenes and Zeuxis, who died laughing.

Pantagruel and his companions cite examples of individuals who, despite their beneficial and admired contributions during their lifetimes, have left behind a legacy of adverse consequences following their demise, often accompanied by significant natural or social upheavals.

The lengthy lists provide detailed descriptions of the anatomy and behavior of this character, who is described as a "very tall Lantern Bearer, standard-bearer of the Ichthyophages, dictator of the Mustardois, flogger of little children, and flatterer of doctors.

The 78 internal and 64 external parts of his body, along with the 36 traits of his behavior, portray a grotesque figure that employs terminology derived from medicine and rhetoric (notably elements from Rhetorica ad Herennium).

[N 8] Beyond the parodic elements, this episode contains allusions to contemporary political and religious events, with the Andouilles identified with the Protestants rebelling against Charles V. While the conflict revisits the traditional motif of the battle between carnival and Lent, neither side can be wholly assimilated to one or the other.

The list of dishes and foods sacrificed to their pot-bellied god is then presented: fried bits, wild boar heads, pork loins with peas, squabs, grilled capons, multicolored dragees, and so forth.

While late 19th and early 20th-century commentators like Jean Fleury or Alfred Glauser [fr] perceive a sign of dull fatigue in this scatological outburst, more recent critics reveal its allegorical implications and allusive nature.

[MH 30] Therefore, the definition of "cannibal" as "a monstrous people in Africa, having a face like dogs, and abounding in a place of laughter" does not align with the meaning attributed to the term by Peter Martyr d'Anghiera, who characterized the cruel inhabitants of the Antilles.

The rejection of a material motive in favor of a spiritual mission aligns with the discourse of other contemporary travelers, such as the naturalist Pierre Belon and the cosmographer André Thevet, as evidenced in the preface to Cosmographie universelle.

The myth of the Argonauts, explicitly mentioned in the novel, directly refers to the political tribulations of the time, as illustrated by the order emphasized by Charles V or the depiction of Henry II under the guise of Tiphys.

The reflection on proper names that opens in chapter 37, when the captains Riflandouille and Tailleboudin are summoned, thus recalls statements similar to those developed in the preface of a posthumous work by Du Bellay printed in 1569, Xenia, seu illustrium quorundam nominum allusions.

[66] In this way, Frank Lestringant encourages an examination of the islands as geographical allegories, wherein their heterotopic dimension enables the staging of a distinct otherness, designed to stimulate the imagination and evoke a sense of wonder.

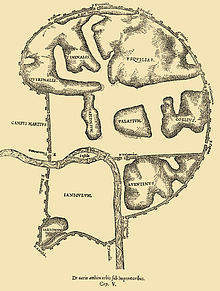

The initial inhabitants of this locale who encounter Pantagruel present an illustrative representation, as they include a monk, a falconer, a solicitor, and a winemaker, corresponding respectively to the clergy, nobility, legal professionals, and commoners.

The satire aligns with its etymological sense related to mixture, encompassing the intertwining of narratives, cross-borrowing from different theatrical genres such as farce and tragicomedy, and the interweaving of dissimilar themes including the religious and the scatological.

The interactions between the devil and the peasant provide opportunities for Rabelais to make jabs at the lust of the monks, as well as to satirize other aspects of society, including the greed of lawyers, the deceit of merchants, and the cunning of chamberlains.

[80] In his work, Verdun-Léon Saulnier [fr] offers support for the thesis of Rabelais's hesychasm, which may be defined as an attitude of renunciation of active propaganda, akin to quietism, and a desire to live in peace.

[86] Michael Screech states that while the novel aligns with the political line of the King of France and the politico-religious context flourishes more than in previous works, the propagandistic dimension is only one among others, as evidenced by the passages that are primarily entertaining and comedic.

In the episode of the Papimanes, Homenaz represents a fixed and rigid conception of language, mired in the sensible and the literal, whereas Pantagruel, open to polysemy, does not fear lexical innovation, as illustrated by the naming of the pears received as a gift.

Upon reaching the frozen words, he does not hesitate to formulate several hypotheses regarding their meaning, in contrast to his companions, who are rendered speechless by what they hear without seeing, and the captain, who reduces the extraordinary phenomenon to the memory of a past battle.

The colors of heraldry and the science of symbols recall the conventional character of the meaning attributed to the sign, and Pantagruel's final hypothesis regarding Orpheus's song evokes the poetic dimension of the frozen words.

In addition to the episode of the frozen words, the devilry of François Villon gives rise to a noisy hubbub, with actors parading through the city with their cymbals and bells, the wedding of Basché set to the sound of musical instruments, and a cannonade concluding Le Quart Livre.

The concept is also employed by poets, as evidenced by Antonio Minturno's commentary on the ambiguous nature of Plautus's Amphitryon, and in vernacular literature, as illustrated by the preface to Théodore Beza's Abraham Sacrificing, which specifies the dual character of his play.

[114] The text is imbued with a polemical charge, which is evidenced by the anatomical description provided by Quaresmeprenant, the rewriting of the androgynous myth in the guise of Antiphysie, and the ambiguities related to Priapus (the pun between mens [mind] and mentula [penis]).

The stercoraire (excremental reference) retains its denigrating and moralizing dimension when Gaster reminds the matagots (a type of peasant) that he is not God but merely a humble creature, inviting them to seek a trace of divinity in his droppings, thereby denouncing the scandal of the Incarnation.

[121] A True History by Lucian, The Macaronics by Teofilo Folengo, and The Disciple of Pantagruel [fr], ascribed to Jehan d'Abundance, represent three significant sources of inspiration for Rabelaisian themes in Le Quart Livre.