Leyden jar

[2] Its invention was a discovery made independently by German cleric Ewald Georg von Kleist on 11 October 1745 and by Dutch scientist Pieter van Musschenbroek of Leiden (Leyden), Netherlands, in 1745–1746.

[5] Thales of Miletus, a pre-Socratic philosopher, is thought to have accidentally commented on the phenomenon of electrostatic charging, due to his belief that even lifeless things have a soul in them, hence the popular analogy of the spark.

The Leyden jar was effectively discovered independently by two parties: German dean Ewald Georg von Kleist, who made the first discovery, and Dutch scientists Pieter van Musschenbroek and Andreas Cunaeus, who figured out why it only worked when held in the hand.

[9] In October 1745, von Kleist tried to accumulate electricity in a small medicine bottle filled with alcohol with a nail inserted in the cork.

Von Kleist knew that the glass would provide an obstacle to the escape of the "fluid", and so was convinced that a substantial electric charge could be collected and held within it.

[citation needed] The Leyden jar's invention was long credited to Pieter van Musschenbroek, the physics professor at Leiden University, who also ran a family foundry which cast brass cannonettes, and a small business (De Oosterse Lamp – "The Eastern Lamp") which made scientific and medical instruments for the new university courses in physics and for scientific gentlemen keen to establish their own 'cabinets' of curiosities and instruments.

[16] Musschenbroek's outlet in France for the sale of his company's 'cabinet' devices was the Abbé Nollet (who started building and selling duplicate instruments in 1735[17]).

Nollet then gave the electrical storage device the name "Leyden jar" and promoted it as a special type of flask to his market of wealthy men with scientific curiosity.

[21] In 1746, Abbé Nollet performed two experiments for the edification of King Louis XV of France, in the first of which he discharged a Leyden jar through 180 royal guardsmen, and in the second through a larger number of Carthusian monks; all of whom sprang into the air more or less simultaneously.

[21] In 1746–1748, Benjamin Franklin experimented with charging Leyden jars in series,[23] and developed a system involving 11 panes of glass with thin lead plates glued on each side, and then connected together.

The Swedish physicist, chemist, and meteorologist Torbern Bergman translated much of Benjamin Franklin's writings on electricity into German and continued to study electrostatic properties.

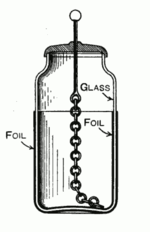

A metal rod electrode projects through the nonconductive stopper at the mouth of the jar, electrically connected by some means (usually a hanging chain) to the inner foil, to allow it to be charged.

[30] The original form of the device is just a glass bottle partially filled with water, with a metal wire passing through a cork closing it.

[31] These developments inspired William Watson in the same year to have a jar made with a metal foil lining both inside and outside, dropping the use of water.

[33] Further developments in electrostatics revealed that the dielectric material was not essential, but increased the storage capability (capacitance) and prevented arcing between the plates.

In the 1700s American statesman and scientist Benjamin Franklin performed extensive investigations of both water-filled and foil Leyden jars, which led him to conclude that the charge was stored in the glass, not in the water.

[35] Addenbrooke (1922) found that in a dissectible jar made of paraffin wax, or glass baked to remove moisture, the charge remained on the metal plates.

[40] The center rod electrode has a metal ball on the end to prevent leakage of the charge into the air by corona discharge.

Originally, the amount of capacitance was measured in number of 'jars' of a given size, or through the total coated area, assuming reasonably standard thickness and composition of the glass.

By the middle of the 19th century, the Leyden jar had become common enough for writers to assume their readers knew of and understood its basic operation.