Electrical resistance and conductance

The resistance of an object depends in large part on the material it is made of.

Objects made of electrical insulators like rubber tend to have very high resistance and low conductance, while objects made of electrical conductors like metals tend to have very low resistance and high conductance.

The nature of a material is not the only factor in resistance and conductance, however; it also depends on the size and shape of an object because these properties are extensive rather than intensive.

For example, a wire's resistance is higher if it is long and thin, and lower if it is short and thick.

The resistance R of an object is defined as the ratio of voltage V across it to current I through it, while the conductance G is the reciprocal:

In the hydraulic analogy, current flowing through a wire (or resistor) is like water flowing through a pipe, and the voltage drop across the wire is like the pressure drop that pushes water through the pipe.

The resistance and conductance of a wire, resistor, or other element is mostly determined by two properties: Geometry is important because it is more difficult to push water through a long, narrow pipe than a wide, short pipe.

The difference between copper, steel, and rubber is related to their microscopic structure and electron configuration, and is quantified by a property called resistivity.

In addition to geometry and material, there are various other factors that influence resistance and conductance, such as temperature; see below.

A piece of conducting material of a particular resistance meant for use in a circuit is called a resistor.

Resistors, on the other hand, are made of a wide variety of materials depending on factors such as the desired resistance, amount of energy that it needs to dissipate, precision, and costs.

Therefore, the resistance and conductance of objects or electronic components made of these materials is constant.

The current–voltage graph of an ohmic device consists of a straight line through the origin with positive slope.

The resistance of a given object depends primarily on two factors: what material it is made of, and its shape.

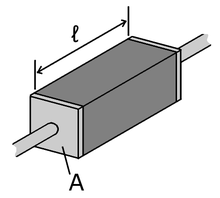

The resistance R and conductance G of a conductor of uniform cross section, therefore, can be computed as

Resistivity is a measure of the material's ability to oppose electric current.

This formula is not exact, as it assumes the current density is totally uniform in the conductor, which is not always true in practical situations.

Similarly, if two conductors near each other carry AC current, their resistances increase due to the proximity effect.

In an insulator, such as Teflon, each electron is tightly bound to a single molecule so a great force is required to pull it away.

Also called dynamic, incremental, or small-signal resistanceIt is the derivative of the voltage with respect to the current; the slope of the current–voltage curve at a point

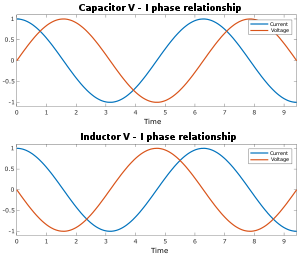

where: The impedance and admittance may be expressed as complex numbers that can be broken into real and imaginary parts:

In general, AC systems are designed to keep the phase angle close to 0° as much as possible, since it reduces the reactive power, which does no useful work at a load.

A key feature of AC circuits is that the resistance and conductance can be frequency-dependent, a phenomenon known as the universal dielectric response.

The dissipation of electrical energy is often undesired, particularly in the case of transmission losses in power lines.

As another example, incandescent lamps rely on Joule heating: the filament is heated to such a high temperature that it glows "white hot" with thermal radiation (also called incandescence).

This effect may be undesired, causing an electronic circuit to malfunction at extreme temperatures.

Therefore, these components can be used in a circuit-protection role similar to fuses, or for feedback in circuits, or for many other purposes.

In general, self-heating can turn a resistor into a nonlinear and hysteretic circuit element.

See the discussion on strain gauges for details about devices constructed to take advantage of this effect.

Some resistors, particularly those made from semiconductors, exhibit photoconductivity, meaning that their resistance changes when light is shining on them.