Leo Frank

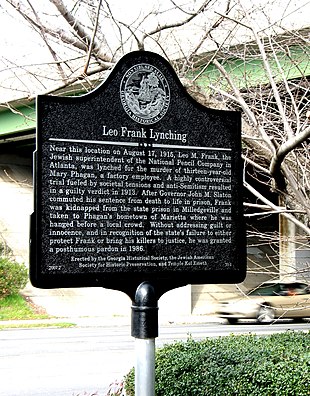

Leo Max Frank (April 17, 1884 – August 17, 1915) was an American lynching victim convicted in 1913 of the murder of 13-year-old Mary Phagan, an employee in a factory in Atlanta, Georgia where he was the superintendent.

Marx said the new Russian Jews were "barbaric and ignorant" and believed their presence would create new antisemitic attitudes and a situation which made possible Frank's guilty verdict.

[12] Historian Leonard Dinnerstein summarized Atlanta's situation in 1913 as follows: The pathological conditions in the city menaced the home, the state, the schools, the churches, and, in the words of a contemporary Southern sociologist, the 'wholesome industrial life.'

"[n 7] Lee was arrested that morning based on these notes and his apparent familiarity with the body – he stated that the girl was white, when the police, because of the filth and darkness in the basement, initially thought she was black.

"[58] The agency quickly became disillusioned with the many societal implications of the case, most notably the notion that Frank was able to evade prosecution due to his being a rich Jew, buying off the police and paying for private detectives.

His story was called into question when a witness told detectives that "a black negro ... dressed in dark blue clothing and hat" had been seen in the lobby of the factory on the day of the murder.

The governor, noting the reaction of the public to press sensationalism soon after Lee's and Frank's arrests, organized ten militia companies in case they were needed to repulse mob action against the prisoners.

Dinnerstein wrote, "Characterized by innuendo, misrepresentation, and distortion, the yellow journalism account of Mary Phagan's death aroused an anxious city, and within a few days, a shocked state.

"[78] Albert Lindemann, author of The Jew Accused, opined that "ordinary people" may have had difficulty evaluating the often unreliable information and in "suspend[ing] judgment over a long period of time" while the case developed.

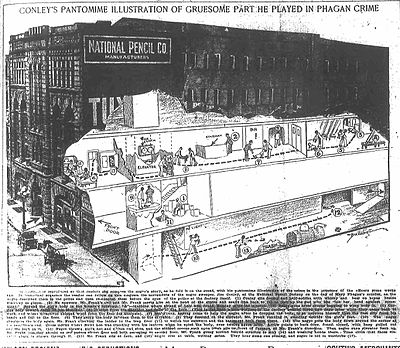

[88] To support their theory that the murder occurred on the factory's second floor in the machine room near Frank's office, the prosecution presented witnesses who testified to bloodstains and strands of hair found on the lathe.

Lee told police that Gantt, a former employee who had been fired by Frank after $2 was found missing from the cash box, wanted to look for two pairs of shoes he had left at the factory.

"[126] On August 26, the day after the guilty verdict was reached by the jury, Judge Roan brought counsel into private chambers and sentenced Frank to death by hanging, with the date set to October 10.

[136][137] The dissenting justices restricted their opinion to Conley's testimony, which they declared should not have been allowed to stand: "It is perfectly clear to us that evidence of prior bad acts of lasciviousness committed by the defendant ... did not tend to prove a preexisting design, system, plan, or scheme, directed toward making an assault upon the deceased or killing her to prevent its disclosure."

)[146] During the defense's closing argument, the issue of the repudiations was put to rest by Judge Hill's ruling that the court could only consider the revocation of testimony if the subject were tried and found guilty of perjury.

However, Holmes said, "I very seriously doubt if the petitioner ... has had due process of law ... because of the trial taking place in the presence of a hostile demonstration and seemingly dangerous crowd, thought by the presiding Judge to be ready for violence unless a verdict of guilty was rendered.

During the hearing, former Governor Joseph Brown warned Slaton, "In all frankness, if Your Excellency wishes to invoke lynch law in Georgia and destroy trial by jury, the way to do it is by retrying this case and reversing all the courts.

"[181] In response, Slaton invited the press to his home that afternoon, telling them: All I ask is that the people of Georgia read my statement and consider calmly the reasons I have given for commuting Leo M. Frank's sentence.

[185] However, on July 17, The New York Times reported that fellow inmate William Creen tried to kill Frank by slashing his throat with a 7-inch (18 cm) butcher knife, severing his jugular vein.

The Constitution alone assumed Frank's guilt, while both the Georgian and the Journal would later comment about the public hysteria in Atlanta during the trial, each suggesting the need to reexamine the evidence against the defendant.

[188] On March 14, 1914, while the extraordinary motion hearing was pending, the Journal called for a new trial, saying that to execute Frank based on the atmosphere both within and outside the courtroom would "amount to judicial murder."

L. O. Bricker, the pastor of the church attended by Phagan's family, said that based on "the awful tension of public feeling, it was next to impossible for a jury of our fellow human beings to have granted him a fair, fearless and impartial trial.

He received at final count close to a hundred thousand letters of sympathy in jail, and prominent figures throughout the country, including governors of other states, U.S. senators, clergymen, university presidents, and labor leaders, spoke up in his defense.

When the Journal called for a reevaluation of the evidence against Frank, Watson, in the March 19, 1914, edition of his magazine, attacked Smith for trying "to bring the courts into disrepute, drag down the judges to the level of criminals, and destroy the confidence of the people in the orderly process of the law.

C. Vann Woodward writes that Watson "pulled all the stops: Southern chivalry, sectional animus, race prejudice, class consciousness, agrarian resentment, state pride.

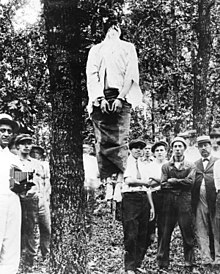

[209] The New York Times reported Frank was handcuffed, his legs tied at the ankles, and that he was hanged from a branch of a tree at around 7:00 a.m., facing the direction of the house where Phagan had lived.

[210] The Atlanta Journal wrote that a crowd of men, women, and children arrived on foot, in cars, and on horses, and that souvenir hunters cut away parts of his shirt sleeves.

)[216] On August 19, 1915, The New York Times reported that the vast majority of Cobb County believed Frank had received his "just deserts", and that the lynch mob had simply stepped in to uphold the law after Governor Slaton arbitrarily set it aside.

Despite this, Charles Willis Thompson of The New York Times said that the citizens of Marietta "would die rather than reveal their knowledge or even their suspicion [of the identities of the lynchers]", and the local Macon Telegraph said, "Doubtless they can be apprehended – doubtful they will.

According to Elaine Marie Alphin, author of An Unspeakable Crime: The Prosecution and Persecution of Leo Frank, they were selling so fast that the police announced that sellers would require a city license.

"[260][261] In 2019, Fulton County District Attorney Paul Howard founded an eight-member panel called the Conviction Integrity Unit to investigate the cases of Wayne Williams and Frank.