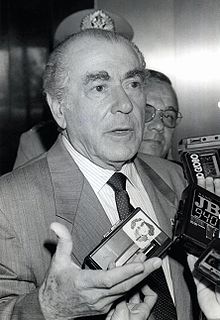

Leonel Brizola

An engineer by training, Brizola organized the youth wing of the Brazilian Labour Party and served as state representative for Rio Grande do Sul and mayor of its capital, Porto Alegre.

In 1958 he was elected governor of Rio Grande do Sul and subsequently played a major role in thwarting a first coup attempt by sectors of the armed forces, who wished to prevent João Goulart from assuming the presidency following the resignation of Jânio Quadros in August 1961, under allegations of communist ties.

[citation needed] As governor of Rio Grande do Sul (1959–63), Brizola rose to prominence for his social policies that included the quick building of public schools in poor neighborhoods across the state (brizoletas).

[12] After winning support from local army commander general Machado Lopes, Brizola forged the cadeia da legalidade (legality broadcast) from a pool of radio stations in Rio Grande do Sul, which issued a nationwide call from the Piratini Palace denouncing the intentions behind the Cabinet ministers' actions and encouraging common citizens to protest in the streets.

Brizola surrendered the State Police Force to the regional army command and began organizing paramilitary Committees of Democratic Resistance, and considered handing out firearms to civilians.

[14] Brizola gained international attention for his nationalist policies; as governor he developed his plan for quick industrialization of the state, a program for the constitution of state-owned industrial utilities,[15] that led him to nationalize American public utilities trusts' assets in Rio Grande, such as ITT and Electric Bond & Share (local branch of American & Foreign Power Company (Amforp for short), itself owned by the holding Electric Bond and Share Company ).

[23] ITT had been also operating at a loss; nevertheless, as it had already been taken by surprise by the expropriation of its property in Cuba by Fidel Castro, the nationalization of its Brazilian operation - no matter how unprofitable - was seem by it as something that could set a precedent to the whole of Latin America.Therefore, the fact that ITT decided to enlist for support from Washington[24] The Brizola nationalizations became headline news in the American press when the John F. Kennedy administration was trying to counter the "Communist infiltration" in Brazil[25] by striking a deal with Goulart that included U.S. financial aid to the Brazilian federal government.

[27][28][29] Goulart gave in to American pressure on the issue, accepting to pay what the Left considered excessive compensations to both ITT & Amforp in exchange for financial aid, Brizola presented his in-law as a defector from the nationalist cause.

He was seen as personally authoritarian and quarrelsome, and capable of dealing with his enemies using physical aggression; for example he hit rightwing journalist David Nasser at Rio de Janeiro airport.

[33] At the same time, in a move to vye with Goulart for political leadership, Brizola started a weekly Friday talkshow on the Rio radio broadcast Mayrink Veiga that was owned by Congressman from São Paulo State Miguel Leuzzi,[34] which he used to broadcast nationwide, and planned to constitute a network of political cells composed of small groups of armed men; the "elevensome" Grupos de Onze—paramilitary parties modeled on a soccer team.

[40] Dantas, who negotiated the 1963 U.S.-Brazil financial agreement, had been received in Washington "more like a head of state than a minister of finance", and expected to be greeted at his homecoming "with appreciation if not fanfare"; a hope Brizola quickly dashed with "venomous attacks".

[55] In a March 1964 State Department telegram sent to the American ambassador in Brazil, U.S. support of the incoming military coup was equated with denying Goulart and Brizola a position of democratic legitimacy that allowed them to adopt their "extremist" plans.

[57] According to José Murilo de Carvalho, Brizola's aggressive stance towards the reforming process was more coherent than Goulart's, who supported a reformist agenda but eschewed the necessary use of force to foster it.

Brizola was the only political leader to support for the president, sheltering him in Porto Alegre and hoping a bid to rouse the local army units towards the restoration of the toppled régime could be made.

[64] In early 1965, a group of Brizola's sympathizers—mostly Army NCOs— tried and failed to articulate a theater of guerrilla warfare in the Eastern Brazilian mountains around Caparaó, which was only underground military training that was suppressed without incident.

[67] Except for this episode, Brizola spent the first ten years of the Brazilian military dictatorship mostly alone in Uruguay, where he managed his wife's landed property and kept abreast of domestic news from various opposition movements in Brazil.

He rejected attempts at being recruited into the Frente Ampla (Broad Front), a mid-1960s informal caucus of pre-dictatorship leaders intent on pressuring for re-democratization, which included Carlos Lacerda and Juscelino Kubitschek.

[75] Between late 1976 and early 1977, the fact that all three most prominent members of the Frente Ampla - Juscelino Kubitscheck, João Goulart himself and Carlos Lacerda - had all died in succession and in somewhat mysterious circumstances,[76] made Brizola feel increasingly threatened in Uruguay.

[87] Other identity groups were sought for special attention; Northeastern Brazilians, marginalized children and females in general— which made the intended party appear to be vying for mass appeal rather than a core trade unionist base.

the Brazilian military dictatorship was waning; in 1978, passports were quietly given to prominent political exiles but Brizola, alongside a core group of alleged radicals described as "public enemy number one", remained blacklisted and was refused the right of return.

Brizola returned to Brazil with the intention of restoring the Brazilian Labour Party as a radical, nationalist, left-wing, mass movement and as a confederacy of historical Getulist leaders.

Brizola was denied the right to use the historical name of the Brazilian Labour Party, previously conceded to a rival group centered around a military dictatorship-friendly figure, Congresswoman Ivete Vargas—the grand-niece of Getúlio Vargas.

He ran a ticket of candidates for Congress that tried to compensate for his party's lack of cadres by offering a roster of people with no previous ties to professional politics, such as the Native Brazilian leader Mário Juruna, the singer Agnaldo Timóteo, and a sizeable number of Afro-Brazilian activists.

[103] Brizola centered his personal campaign on issues such as education and public security, offering a candidacy that had clear, oppositional overtones and proposed to upheld the Vargoist legacy.

During the early ballot-counting process, Proconsult repeatedly supplied media with communiqués offering belated voting statistics from rural areas, where Brizola was at a disadvantage, which were immediately echoed by TV Globo.

[107] By denouncing this alleged fraud at press conferences, interviews, and public statements—which included a discussion with Globo CEO Armando Nogueira on live television—[108] Brizola pre-empted the scheme of any chance of success, as official ballot numbers eventually gave him the lead.

[112] The right opposed these policies, saying they made slums an open territory for organized crime represented by huge gangs like Comando Vermelho (Red Command), by means of a conflation between common criminality and leftism.

[113] Brizola's policies included porkbarrel,[114] poor management, personalism, wild spending of public funds, and displaying a tendency at opportunistic, short term solutions.

Brizola refused, preferring to present himself as a candidate to the gubernatorial elections in the same year, winning a second term as Governor of Rio de Janeiro by a first-round majority of 60.88% of all valid ballots.

[125] It was the end of Brizolismo as a national political force; some weeks before the election, a kiosk in downtown Rio de Janeiro where Brizolandia cronies met was demolished by City Hall officers and was never rebuilt.