Lepidosauria

The Lepidosauria (/ˌlɛpɪdoʊˈsɔːriə/, from Greek meaning scaled lizards) is a subclass or superorder of reptiles, containing the orders Squamata and Rhynchocephalia.

[2] Squamata contains over 9,000 species, making it by far the most species-rich and diverse order of non-avian reptiles in the present day.

[4] However, it is represented by only one living species: the tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus), a superficially lizard-like reptile native to New Zealand.

[5][6] Lepidosauria is a monophyletic group (i.e. a clade), containing all descendants of the last common ancestor of squamates and rhynchocephalians.

Purely in the context of modern taxa, Lepidosauria can be considered the sister taxon to Archelosauria, which includes Testudines (turtles), Aves (birds) and Crocodilia (crocodilians).

Lepidosauria is encompassed by Lepidosauromorpha, a broader group defined as all reptiles (living or extinct) closer to lepidosaurs than to archosaurs.

[14] Extant reptiles are in the clade Diapsida, named for two pairs temporal fenestrae present on the skull behind the eye socket.

[30] The tuatara and some extinct rhynchocephalians have a more rigid skull with a complete lower temporal bar closing the lower temporal fenestra formed by the fusion of the jugal and quadrate/quadratojugal bones, similar to the condition found in primitive diapsids.

Male squamates have evolved a pair of hemipenises instead of a single penis with erectile tissue that is found in crocodilians, birds, mammals, and turtles.

In lizards and rhynchocephalians, fracture planes are present within the vertebrae of the tail that allow for its removal.

[16] Third, the scales in lepidosaurs are horny (keratinized) structures of the epidermis, allowing them to be shed collectively, contrary to the scutes seen in other reptiles.

[33] There are three main life history events that lepidosaurs reach: hatching/birth, sexual maturity, and reproductive senility.

[33] Because gular pumping is so common in squamates, and is also found in the tuatara, it is assumed that it is an original trait in the group.

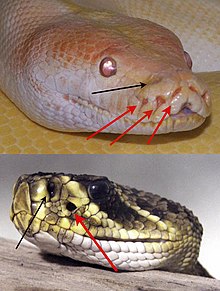

[33] Viperines can sense their prey's infrared radiation through bare nerve endings on the skin of their heads.

[33] The geographic ranges of lepidosaurs are vast and cover all but the most extreme cold parts of the globe.

[29] The tuatara is confined to only a few rocky islands of New Zealand, where it digs burrows to live in and preys mostly on insects.

Bounties were paid for dead cobras under the British Raj in India; similarly, there have been advertised rattlesnake roundups in North America.

[16] People have introduced species to the lepidosaurs' natural habitats that have increased predation on the reptiles.

For example, mongooses were introduced to Jamaica from India to control the rat infestation in sugar cane fields.

Accessories, such as shoes, boots, purses, belts, buttons, wallets, and lamp shades, are all made out of reptile skin.

[16] In 1986, the World Resource Institute estimated that 10.5 million reptile skins were traded legally.