Lepton

Thus electrons are stable and the most common charged lepton in the universe, whereas muons and taus can only be produced in high-energy collisions (such as those involving cosmic rays and those carried out in particle accelerators).

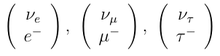

Leptons have various intrinsic properties, including electric charge, spin, and mass.

[6] The next lepton to be observed was the muon, discovered by Carl D. Anderson in 1936, which was classified as a meson at the time.

[7] After investigation, it was realized that the muon did not have the expected properties of a meson, but rather behaved like an electron, only with higher mass.

[8] It was first observed in the Cowan–Reines neutrino experiment conducted by Clyde Cowan and Frederick Reines in 1956.

[8][9] The muon neutrino was discovered in 1962 by Leon M. Lederman, Melvin Schwartz, and Jack Steinberger,[10] and the tau discovered between 1974 and 1977 by Martin Lewis Perl and his colleagues from the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

[11] The tau neutrino remained elusive until July 2000, when the DONUT collaboration from Fermilab announced its discovery.

Exotic atoms with muons and taus instead of electrons can also be synthesized, as well as lepton–antilepton particles such as positronium.

The name lepton comes from the Greek λεπτός leptós, "fine, small, thin" (neuter nominative/accusative singular form: λεπτόν leptón);[14][15] the earliest attested form of the word is the Mycenaean Greek 𐀩𐀡𐀵, re-po-to, written in Linear B syllabic script.

[16] Lepton was first used by physicist Léon Rosenfeld in 1948:[17] Following a suggestion of Prof. C. Møller, I adopt—as a pendant to "nucleon"—the denomination "lepton" (from λεπτός, small, thin, delicate) to denote a particle of small mass.Rosenfeld chose the name as the common name for electrons and (then hypothesized) neutrinos.

The first lepton identified was the electron, discovered by J.J. Thomson and his team of British physicists in 1897.

[27] The tau was first detected in a series of experiments between 1974 and 1977 by Martin Lewis Perl with his colleagues at the SLAC LBL group.

The first evidence for tau neutrinos came from the observation of "missing" energy and momentum in tau decay, analogous to the "missing" energy and momentum in beta decay leading to the discovery of the electron neutrino.

The first detection of tau neutrino interactions was announced in 2000 by the DONUT collaboration at Fermilab, making it the second-to-latest particle of the Standard Model to have been directly observed,[29] with Higgs boson being discovered in 2012.

The spin-statistics theorem thus implies that they are fermions and thus that they are subject to the Pauli exclusion principle: no two leptons of the same species can be in the same state at the same time.

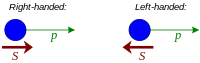

Chirality is a technical property, defined through transformation behaviour under the Poincaré group, that does not change with reference frame.

Right-handed neutrinos and left-handed anti-neutrinos have no possible interaction with other particles (see Sterile neutrino) and so are not a functional part of the Standard Model, although their exclusion is not a strict requirement; they are sometimes listed in particle tables to emphasize that they would have no active role if included in the model.

Even though electrically charged right-handed particles (electron, muon, or tau) do not engage in the weak interaction specifically, they can still interact electrically, and hence still participate in the combined electroweak force, although with different strengths (YW).

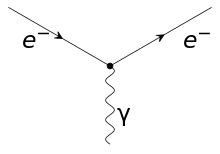

However, higher-order quantum effects caused by loops in Feynman diagrams introduce corrections to this value.

The theoretical and measured values for the electron anomalous magnetic dipole moment are within agreement within eight significant figures.

[32] The results for the muon, however, are problematic, hinting at a small, persistent discrepancy between the Standard Model and experiment.

The charged leptons (i.e. the electron, muon, and tau) obtain an effective mass through interaction with the Higgs field, but the neutrinos remain massless.

For technical reasons, the masslessness of the neutrinos implies that there is no mixing of the different generations of charged leptons as there is for quarks.

The members of each generation's weak isospin doublet are assigned leptonic numbers that are conserved under the Standard Model.

Such a violation is considered to be smoking gun evidence for physics beyond the Standard Model.

[36] This property is called lepton universality and has been tested in measurements of the muon and tau lifetimes and of Z boson partial decay widths, particularly at the Stanford Linear Collider (SLC) and Large Electron–Positron Collider (LEP) experiments.

The decay rate of tau particles through the process τ− → e− + νe + ντ is given by an expression of the same form[36] where K3 is some other constant.

The difference is due to K2 and K3 not actually being constants: They depend slightly on the mass of leptons involved.

Recent tests of lepton universality in B meson decays, performed by the LHCb, BaBar, and Belle experiments, have shown consistent deviations from the Standard Model predictions.

However the combined statistical and systematic significance is not yet high enough to claim an observation of new physics.

W −

boson . The

W −

boson subsequently decays into an electron and an electron antineutrino .