Les Demoiselles d'Avignon

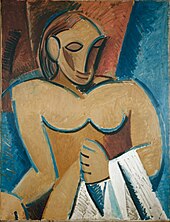

Part of the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, it portrays five nude female prostitutes in a brothel on Carrer d'Avinyó, a street in Barcelona, Spain.

Picasso said the ethnic primitivism evoked in these masks moved him to "liberate an utterly original artistic style of compelling, even savage force" leading him to add a shamanistic aspect to his project.

[3][4][5] Drawing from tribal primitivism while eschewing central dictates of Renaissance perspective and verisimilitude for a compressed picture plane using a Baroque composition while employing Velazquez's confrontational approach seen in Las Meninas, Picasso sought to take the lead of the avant-garde from Henri Matisse.

While he already had a considerable following by the middle of 1906, Picasso enjoyed further success with his paintings of massive oversized nude women, monumental sculptural figures that recalled the work of Paul Gauguin and showed his interest in primitive (African, Micronesian, Native American) art.

He began exhibiting his work in the galleries of Berthe Weill (1865–1951) and Ambroise Vollard (1866–1939), quickly gaining a growing reputation and a following amongst the artistic communities of Montmartre and Montparnasse.

[16] Henri Rousseau (1844–1910), an artist whom Picasso knew and admired and who was not a Fauve, had his large jungle scene The Hungry Lion Throws Itself on the Antelope also hanging near the works by Matisse and which may have had an influence on the particular sarcastic term used in the press.

[29][30] El Greco's painting, which Picasso studied repeatedly in Zuloaga's house, inspired not only the size, format, and composition of Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, but also its apocalyptic power.

According to the English art historian, collector and author of The Cubist Epoch, Douglas Cooper, both of those artists were particularly influential to the formation of Cubism and especially important to the paintings of Picasso during 1906 and 1907.

Nevertheless, the Demoiselles is the logical picture to take as the starting point for Cubism, because it marks the birth of a new pictorial idiom, because in it Picasso violently overturned established conventions and because all that followed grew out of it.

[11][36] Both Picasso and Braque found the inspiration for their proto-Cubist works in Paul Cézanne, who said to observe and learn to see and treat nature as if it were composed of basic shapes like cubes, spheres, cylinders, and cones.

Cézanne's explorations of geometric simplification and optical phenomena inspired Picasso, Braque, Metzinger, Gleizes, Robert Delaunay, Le Fauconnier, Gris and others to experiment with ever more complex multiple views of the same subject, and, eventually to the fracturing of form.

[11] In the autumn of 1906, Picasso followed his previous successes with paintings of oversized nude women, and monumental sculptural figures that recalled the work of Paul Gauguin and showed his interest in primitive art.

In an essay by Dennis Duerden, author of African Art (1968), The Invisible Present (1972), and a former director of the BBC World Service, the mask is defined as "very often a complete head-dress and not just that part that conceals the face".

The example of Picasso virtually launching cubism with his 1907 Desmoiselles d'Avignon, in response to the sorts of African masks and other colonial booty he was encountering in Paris's Musee de l'Homme, is obvious.

[19] Maurice Princet,[58] a French mathematician and actuary, played a role in the birth of Cubism as an associate of Pablo Picasso, Guillaume Apollinaire, Max Jacob, Jean Metzinger, Robert Delaunay, Juan Gris and later Marcel Duchamp.

He let it be known that he regarded the painting as an attempt to ridicule the modern movement; he was outraged to find his sensational Blue Nude, not to speak of Bonheur de vivre, overtaken by Picasso's "hideous" whores.

According to Suzanne Preston Blier, the word bordel in the painting's title, rather than evoking a house of prostitution (une maison close) instead more accurately references in French a complex situation or mess.

Additionally, her article focuses not only on the work itself but also on the critiques and assessments of it that have emerged in the decades since it was initially displayed, prompting readers to think deeply about what reactions to the painting say about viewers and society at large.

Using the earlier sketches—which had been ignored by most critics—he argued that far from evidence of an artist undergoing a rapid stylistic metamorphosis, the variety of styles can be read as a deliberate attempt, a careful plan, to capture the gaze of the viewer.

[1] The earliest sketches feature two men inside the brothel; a sailor and a medical student (who was often depicted holding either a book or a skull, causing Barr and others to read the painting as a memento mori, a reminder of death).

A world of meanings then becomes possible, suggesting the work as a meditation on the danger of sex, the "trauma of the gaze" (to use a phrase of Rosalind Krauss's invention), and the threat of violence inherent in the scene and sexual relations at large.

"[80] A few years after writing The Philosophical Brothel, Steinberg wrote further about the revolutionary nature of Les Demoiselles: Picasso was resolved to undo the continuities of form and field which Western art had so long taken for granted.

In this one work Picasso discovered that the demands of discontinuity could be met on multiple levels: by cleaving depicted flesh; by elision of limbs and abbreviation; by slashing the web of connecting space; by abrupt changes of vantage; and by a sudden stylistic shift at the climax.

Finally, the insistent staccato of the presentation was found to intensify the picture's address and symbolic charge: the beholder, instead of observing a roomfuI of lazing whores, is targeted from all sides.

For all that the Demoiselles is rooted in Picasso's past, not to speak of such precursors as the Iron Age Iberians, El Greco, Gauguin and Cézanne, it is essentially a beginning: the most innovative painting since Giotto.

[82]Suzanne Preston Blier addresses the history and meaning of Les Demoiselles d'Avignon in a 2019 book in a different way, one that draws on her African art expertise and an array of newly discovered sources she unearthed.

These representations, Blier argues, are central to understanding the painting's creation and help identify the demoiselles as global figures – mothers, grandmothers, lovers, and sisters, living the colonial world Picasso inhabited.

explore various ports of call and the Vienna medical doctor, Karl Heinrich Stratz who holds a human skull or book consistent with the detailed anatomical studies that he provides.

[19] Blier is able to date the painting to late March 1907 directly following the opening of the Salon des Independents where Matisse and Derain had exhibited their own bold, emotionally charged "origins"-themed tableaux.

[70] André Breton later described the transaction: I remember the day he bought the painting from Picasso, who strange as it may seem, appeared to be intimidated by Doucet and even offered no resistance when the price was set at 25,000 francs: "Well then, it's agreed, M.