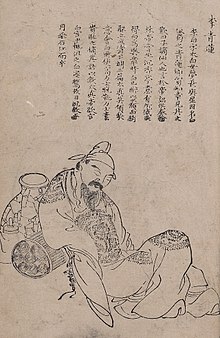

Li Bai

Much of Li's life is reflected in his poems, which are about places he visited; friends whom he saw off on journeys to distant locations, perhaps never to meet again; his own dream-like imaginings, embroidered with shamanic overtones; current events of which he had news; descriptions of nature, perceived as if in a timeless moment; and more.

Li Bai is generally considered to have been born in 701, in Suyab (碎葉) of ancient Chinese Central Asia (present-day Kyrgyzstan),[10] where his family had prospered in business at the frontier.

[11] Afterwards, the family under the leadership of his father, Li Ke (李客), moved to Jiangyou (江油), near modern Chengdu, in Sichuan, when the youngster was about five years old.

In 735, Li Bai was in Shanxi, where he intervened in a court martial against Guo Ziyi, who was later, after becoming one of the top Tang generals, to repay the favour during the An Shi disturbances.

Li's personality fascinated the aristocrats and common people alike, including another Taoist (and poet), He Zhizhang, who bestowed upon him the nickname the "Immortal Exiled from Heaven".

Once, while drunk, Li Bai had gotten his boots muddy, and Gao Lishi, the most politically powerful eunuch in the palace, was asked to assist in the removal of these, in front of the Emperor.

[23] At the persuasion of Yang Guifei and Gao Lishi, Xuanzong reluctantly, but politely, and with large gifts of gold and silver, sent Li Bai away from the royal court.

[24] After leaving the court, Li Bai formally became a Taoist, making a home in Shandong, but wandering far and wide for the next ten some years, writing poems.

[25] He met Du Fu in the autumn of 744, when they shared a single room and various activities together, such as traveling, hunting, wine, and poetry, thus established a close and lasting friendship.

[24] Yelang (in what is now Guizhou) was in the remote extreme southwestern part of the empire, and was considered to be outside the main sphere of Chinese civilization and culture.

Li Bai headed toward Yelang with little sign of hurry, stopping for prolonged social visits (sometimes for months), and writing poetry along the way, leaving detailed descriptions of his journey for posterity.

[24] He had only gotten as far as Wushan, traveling at a leisurely pace, as recorded in the poem "Struggling up the Three Gorges", intimating that it took so long that his hair turned white during the trip up river, towards exile.

[28] When Li received the news of his imperial pardon, he returned down the river to Jiangxi, passing on the way through Baidicheng, in Kuizhou Prefecture, still engaging in the pleasures of food, wine, good company, and writing poetry; his poem "Departing from Baidi in the Morning" records this stage of his travels, as well as poetically mocking his enemies and detractors, implied in his inclusion of imagery of monkeys.

The ninth-century Tang poet Pi Rixiu suggested in a poem that Li had died of chronic thoracic suppuration (pus entering the chest cavity).

[8] According to another source, Li Bai drowned after falling from his boat one day while drunk, as he tried to embrace the reflection of the moon in the Yangtze River.

"[35] Watson adds, as evidence, that of all the poems attributed to Li Bai, about one sixth are in the form of yuefu, or, in other words, reworked lyrics from traditional folk ballads.

[36] As further evidence, Watson cites the existence of a fifty-nine poem collection by Li Bai entitled Gu Feng, or In the Old Manner, which is, in part, tribute to the poetry of the Han and Wei dynasties.

[42] Burton Watson concluded that "[n]early all Chinese poets celebrate the joys of wine, but none so tirelessly and with such a note of genuine conviction as Li [Bai]".

[43] The following two poems, "Rising Drunk on a Spring Day, Telling My Intent" and "Drinking Alone by Moonlight", are among Li Bai's most famous and demonstrate different aspects of his use of wine and drunkenness.

When still sober we share friendship and pleasure, Then, utterly drunk, each goes his own way— Let us join to roam beyond human cares And plan to meet far in the river of stars.

我歌月徘徊。 我舞影零亂。 醒時同交歡。 醉後各分散。 永結無情遊。 相期邈雲漢。 —"Drinking Alone by Moonlight" (Yuèxià dúzhuó 月下獨酌), translated by Stephen Owen[45] An important characteristic of Li Bai's poetry "is the fantasy and note of childlike wonder and playfulness that pervade so much of it".

This may seem sentimental to Western readers, but one should remember the vastness of China, the difficulties of communication... the sharp contrast between the highly cultured life in the main cities and the harsh conditions in the remoter regions of the country, and the importance of family..." It is hardly surprising, he concludes, that nostalgia should have become a "constant, and hence conventional, theme in Chinese poetry.

"[46] Liu gives as a prime example Li's poem "A Quiet Night Thought" (also translated as "Contemplating Moonlight"), which is often learned by schoolchildren in China.

Shu is a poetic term for Sichuan, the destination of refuge that Emperor Xuanzong considered fleeing to escape the approaching forces of the rebel General An Lushan.

Yet she notes the persistence of "what we can rightly call the 'Li-Du debate', the terms of which became so deeply ingrained in the critical discourse surrounding these two poets that almost any characterization of the one implicitly critiqued the other".

These meetings and separations were typical occasions for versification in the tradition of the literate Chinese of the time, a prime example being his relationship with Du Fu.

In China, his poem "Quiet Night Thoughts", reflecting a nostalgia of a traveller away from home,[55] has been widely "memorized by school children and quoted by adults".

Austrian composer Gustav Mahler used German adaptations of four of Li's poems as texts for four of the songs in his song-symphony Das Lied von der Erde in 1908.

Some, like Changgan xing (translated by Ezra Pound as "The River Merchant's Wife: A Letter"),[59] record the hardships or emotions of common people.

An example of the liberal, but poetically influential, translations, or adaptations, of Japanese versions of his poems made, largely based on the work of Ernest Fenollosa and professors Mori and Ariga.