Liberty Bell

In its early years, the bell was used to summon lawmakers to legislative sessions and to alert citizens to public meetings and proclamations.

"[1] After World War II, Philadelphia allowed the National Park Service to take custody of the bell, while retaining ownership.

The original bell hung from a tree behind the Pennsylvania State House, now known as Independence Hall, and was said to have been brought to the city by its founder, William Penn.

[2] Isaac Norris, speaker of the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly, gave orders to the colony's London agent, Robert Charles, to obtain a "good Bell of about two thousands pound weight".

[3] We hope and rely on thy care and assistance in this affair and that thou wilt procure and forward it by the first good oppo as our workmen inform us it will be much less trouble to hang the Bell before their Scaffolds are struck from the Building where we intend to place it which will not be done 'till the end of next Summer or beginning of the Fall.

[18] The result was "an extremely brittle alloy which not only caused the Bell to fail in service but made it easy for early souvenir collectors to knock off substantial trophies from the rim".

[21] On October 16, 1755, in one of the earliest documented mentions of the bell's use, Benjamin Franklin wrote Catherine Ray a letter, which stated: "Adieu.

[24] As the American Revolutionary War intensified, delegates to the Second Continental Congress and colonial-era city officials and citizens of Philadelphia were acutely aware that the British Army would likely recast the bell into munitions if they were able to find and secure it.

On September 11, 1777, these concerns escalated after Washington and the Continental Army were defeated in the Battle of Brandywine, leaving the revolutionary capital of Philadelphia defenseless.

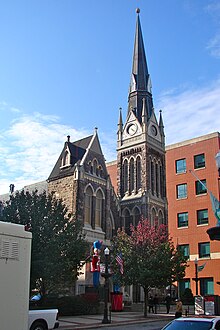

In Allentown, the Liberty Bell was hidden under the church's floor boards just as the British were entering and beginning their occupation of Philadelphia.

David Kimball, in a book authored for the National Park Service, suggests that it most likely cracked sometime between 1841 and 1845, during its ringing on either Independence Day or on Washington's Birthday.

[36] A great part of the modern image of the bell as a relic of the proclamation of American independence was forged by writer George Lippard.

[37] The short story depicted an aged bellman on July 4, 1776, sitting morosely by the bell, fearing that Congress would not have the courage to declare independence.

[39] The elements of the story were reprinted in early historian Benson J. Lossing's The Pictorial Field Guide to the Revolution (published in 1850) as historical fact,[40] and the tale was widely repeated for generations after in school primers.

[44] At the time, Independence Hall was also used as a courthouse, and African-American newspapers pointed out the incongruity of housing a symbol of liberty in the same building in which federal judges were holding hearings under the Fugitive Slave Act.

[47] Nevertheless, between 120,000 and 140,000 people were able to pass by the open casket and then the bell, carefully placed at Lincoln's head so mourners could read the inscription, "Proclaim Liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof.

Myriad souvenirs were sold bearing its image or shape, and state pavilions contained replicas of the bell made of substances ranging from stone to tobacco.

In Biloxi, Mississippi, the former President of the Confederate States of America, Jefferson Davis, visited the bell and delivered a speech paying homage to it and urging national unity.

[55] Philadelphians began to cool to the idea of sending it to other cities when it returned from Chicago bearing a new crack, and each new proposed journey met with increasing opposition.

The city finally agreed to let it be transported to San Francisco since it had never been west of St. Louis, and it was a chance to allow millions of Americans to see it who might never again have the opportunity.

[60] In 1914, fearing that the cracks might lengthen during the long train ride to San Francisco, Philadelphia installed a metal support structure inside the bell, called the "spider".

[61] In February 1915, the bell was tapped gently with wooden mallets to produce sounds that were transmitted to the fair as the signal to open it, a transmission that also inaugurated transcontinental telephone service.

[71] After World War II, and following considerable controversy, the City of Philadelphia agreed that it would transfer custody of the bell and Independence Hall, while retaining ownership, to the federal government.

The purpose of this campaign, as Vice President Alben Barkley put it, was to make the country "so strong that no one can impose ruthless, godless ideologies on us".

Instead, in 1973, the Park Service proposed to build a smaller glass pavilion for the bell at the north end of Independence Mall, between Arch and Race streets.

[79] During the Bicentennial, members of the Procrastinators' Club of America jokingly picketed the Whitechapel Bell Foundry with signs "We got a lemon" and "What about the warranty?"

[88] The project became highly controversial when it was revealed that Washington's slaves had been housed only feet from the planned LBC's main entrance.

[92] The new facility that opened hours after the bell was installed on October 9, 2003, is adjacent to an outline of Washington's slave quarters marked in the pavement, with interpretive panels explaining the significance of what was found.

After the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment (granting women the vote), the Justice Bell was brought to the front of Independence Hall on August 26, 1920, to finally sound.

It remained on a platform before Independence Hall for several months before city officials required that it be taken away, and today is at the Washington Memorial Chapel at Valley Forge.