Limes Mauretaniae

The transitions on the Limes Africanus between Roman territory and the free tribal areas were fluid and were monitored only by the garrisons of a few outposts.

The greatest danger was posed by the nomadic Berber tribes, which carried on sporadic warfare with Rome The chain of forts was primarily intended to mark the Roman domain.

In many areas, the system also served to control and channel the migratory movements of nomadic tribes or peoples, including the monitoring and reporting of their activities, and as a customs border.

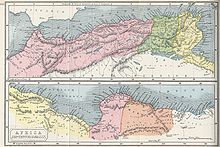

The eastern border of the province of Mauretania Caesariensis (identical to the eastern border of the later province of Sitifensis) ran approximately on a line west of Cape Bougaroun on the Ampsaga River[3][4] to the east end of the Chott el Hodna and further west into the steppe landscape.

The Roman area of influence, which was originally limited to the coast of Caesariensis, was extended further south for economic reasons into the Maghreb from the 1st to the 3rd century.

In the north, the foothills of the Rif Mountains drop steeply into the sea, preventing a direct land connection along the coast.

The road network established by the Romans in North Africa ensured good and timely logistical connections for the trade and supply of their widely deployed troops.

At the beginning of the dry season, nomads and hill tribes moved to the coastal regions, hired themselves out as workers, and exchanged agricultural products for animals from their herds.

The border security system was largely adapted to the circumstances of the topography, but also to the behavior and lifestyle of the ethnic groups living at that location, and was therefore hardly fortified in spots.

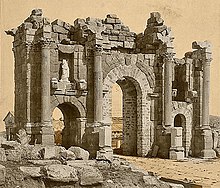

East of the Monts du Hodna there was a system of clausurae, the Fossatum Africae, which "consisted of a ditch, wall, watch-towers, and gates."

The Roman-occupied area of the province of Mauretania Caesariensis was defined by a line of fortifications running along the Chelif River (Chinalaph).

Beginning around 197 AD, the Severan emperors built a series of forts in western Caesariensis on the northern border of the plateau.

Likewise, the easily accessible coastal areas of central and southern Morocco south of Rabat remained outside the Roman sphere of influence.

Because of the pirate threat, both coastal protection and the inland river Sububus (Sebou) were strengthened from the 2nd century onwards by the construction of forts in Thamusida, Iulia Valentia Banasa, and Tremuli (Souk El Arbaa).

On the coast, the Sala was closed off from the Atlantic to the Bou Regreg by an 11-kilometre (6.8 mi)-long moat, which was partially reinforced with a wall, four small forts, and around 15 watchtowers.

Additional forts were built in Tamuda (Tétouan), Souk El Arbaa, and Oppidum Novum (Ksar el-Kebir) on the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts.

Due to increasing attacks by local tribes, the border in Tingitana was withdrawn to the line Frigidae (Azib el Harrak[7])–Thamusida[7] under Diocletian in the second half of the 3rd century.

The smaller military posts, called fortlets or burgi, had a size of only 0.01–0.10 ha (0.025–0.247 acres), reinforced walls, no windows and only a small garrison.

For defense and protection against uprisings and raids by nomadic and hill tribes, the Legio III Augusta was the only legion in North Africa outside of Egypt since the time of Augustus.

The existing armed forces had the task of protecting the border line against raids from the steppe, mountain, and desert areas, but on the other hand they were not allowed to pose a threat to Rome.

This balancing assessment between sufficient military means to avert an external danger and at the same time avoid an internal threat applied in principle to all provinces.

Although the military potential was apparently temporarily overwhelmed, the legion and auxiliary units in North Africa were basically able to fulfill their mission.

In this way, in the time of Tiberius, the Legio IX Hispana moved temporarily from Pannonia to North Africa in 17 AD to fight against the rebellion of Tacfarinas.