Line shaft

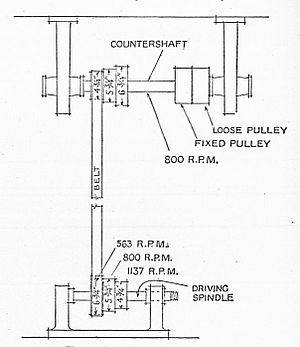

In manufacturing where there were a large number of machines performing the same tasks, the design of the system was fairly regular and repeated.

Belts were often twisted 180 degrees per leg and reversed on the receiving pulley to cause the second shaft to rotate in the opposite direction.

In 1828 in Lowell, Massachusetts, Paul Moody substituted leather belting for metal gearing to transfer power from the main shaft running from a water wheel.

This innovation quickly spread in the U.S.[2] Flat-belt drive systems became popular in the UK from the 1870s, with the firms of J & E Wood and W & J Galloway & Sons prominent in their introduction.

The advantages included less noise and less wasted energy in the friction losses inherent in the previously common drive shafts and their associated gearing.

Power buildings continued to be built in the early days of electrification, still using line shafts but driven by an electric motor.

This was also important when a wide range of speed control was necessary for a sensitive operation such as wire drawing or hammering iron.

Eventually Baldwin converted to electric drive, with a substantial saving in labor and building space.

[5] Economical variable speed control using electric motors was made possible by silicon controlled rectifiers (SCRs) to produce direct current and variable frequency drives using inverters to change DC back to AC at the frequency required for the desired speed.

James Hobart said that "We can scarcely step into a shop or factory of any description without encountering a mass of belts which seem at first to monopolize every nook in the building and leave little or no room for anything else.

"[6] To overcome the distance and friction limitations of line shafts, wire rope systems were developed in the late 19th century.

Wire rope operated at higher velocities than line shafts and were a practical means of transmitting mechanical power for a distance of a few miles or kilometers.

They used widely spaced, large diameter wheels and had much lower friction loss than line shafts, and had one-tenth the initial cost.

To supply small scale power that was impractical for individual steam engines, central station hydraulic systems were developed.