Lathe

Most suitably equipped metalworking lathes can also be used to produce most solids of revolution, plane surfaces and screw threads or helices.

The earliest evidence of a lathe dates back to 4th century BC Egypt an is a depiction in the tomb of Petosiris.

There is also tenuous evidence for a turned arifact at a Mycenaean Greek site, dating back as far as the 13th or 14th century BC.

[3] During the Warring States period in China, c. 400 BC, the ancient Chinese used rotary lathes to sharpen tools and weapons on an industrial scale.

[3][5] Pliny later describes the use of a lathe for turning soft stone in his Natural History (Book XXX, Chapter 44).

Precision metal-cutting lathes were developed during the lead up to the Industrial Revolution and were critical to the manufacture of mechanical inventions of that period.

Some of the earliest examples include a version with a mechanical cutting tool-supporting carriage and a set of gears by Russian engineer Andrey Nartov in 1718 and another with a slide-rest shown in a 1717 edition of the French Encyclopédie.

A slide-rest is clearly shown in a 1772 edition of the Encyclopédie and during that same year a horse-powered cannon boring lathe was installed in the Royal Arsenal in Woolwich, England by Jan Verbruggen.

Cannon bored by Verbruggen's lathe were stronger and more accurate than their predecessors and saw service in American Revolutionary War.

Henry Maudslay, the inventor of many subsequent improvements to the lathe worked as an apprentice in Verbruggen's workshop in Woolwich.

[7] During the Industrial Revolution, mechanized power generated by water wheels or steam engines was transmitted to the lathe via line shafting, allowing faster and easier work.

Between the late 19th and mid-20th centuries, individual electric motors at each lathe replaced line shafting as the power source.

Woodturning lathes specialized for turning large bowls often have no bed or tail stock, merely a free-standing headstock and a cantilevered tool-rest.

The counterpoint to the headstock is the tailstock, sometimes referred to as the loose head, as it can be positioned at any convenient point on the bed by sliding it to the required area.

The tail-stock contains a barrel, which does not rotate, but can slide in and out parallel to the axis of the bed and directly in line with the headstock spindle.

Woodturning and metal spinning lathes do not have cross-slides, but rather have banjos, which are flat pieces that sit crosswise on the bed.

In metal spinning, the further pin ascends vertically from the tool-rest and serves as a fulcrum against which tools may be levered into the workpiece.

It can be used to rotate the spindle to a precise angle, then lock it in place, facilitating repeated auxiliary operations done to the workpiece.

Other accessories, including items such as taper turning attachments, knurling tools, vertical slides, fixed and traveling steadies, etc., increase the versatility of a lathe and the range of work it may perform.

The swing determines the diametric size of the object which is capable of being turned in the lathe; anything larger would interfere with the bed.

The term WW refers to the Webster/Whitcomb collet and lathe, invented by the American Watch Tool Company of Waltham, Massachusetts.

Fully automatic mechanical lathes, employing cams and gear trains for controlled movement, are called screw machines.

An adjustable horizontal metal rail, the tool-rest, between the material and the operator accommodates the positioning of shaping tools, which are usually hand-held.

This type of lathe was able to create shapes identical to a standard pattern and it revolutionized the process of gun stock making in the 1820s when it was invented.

[17] The Hermitage Museum, Russia displays the copying lathe for ornamental turning: making medals and guilloche patterns, designed by Andrey Nartov, 1721.

Manually controlled metalworking lathes are commonly provided with a variable-ratio gear-train to drive the main lead-screw.

As well as a wide range of accessories, these lathes usually have complex dividing arrangements to allow the exact rotation of the mandrel.

Because of the difficulty of polishing such work, the materials turned, such as wood or ivory, are usually quite soft, and the cutter has to be exceptionally sharp.

Many types of lathes can be equipped with accessory components to allow them to reproduce an item: the original item is mounted on one spindle, the blank is mounted on another, and as both turn in synchronized manner, one end of an arm "reads" the original and the other end of the arm "carves" the duplicate.

In the United States, ASME has developed the B5.57 Standard entitled "Methods for Performance Evaluation of Computer Numerically Controlled Lathes and Turning Centers", which establishes requirements and methods for specifying and testing the performance of CNC lathes and turning centers.

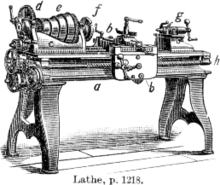

- bed

- carriage (with cross -slide and tool post)

- headstock

- back gear (other gear train nearby drives lead screw)

- cone pulley for a belt drive from an external power source

- faceplate mounted on spindle

- tailstock

- leadscrew

Dead center (bottom)