Vesicle (biology and chemistry)

Vesicles form naturally during the processes of secretion (exocytosis), uptake (endocytosis), and the transport of materials within the plasma membrane.

Vesicles are involved in metabolism, transport, buoyancy control,[2] and temporary storage of food and enzymes.

[3] The 2013 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was shared by James Rothman, Randy Schekman and Thomas Südhof for their roles in elucidating (building upon earlier research, some of it by their mentors) the makeup and function of cell vesicles, especially in yeasts and in humans, including information on each vesicle's parts and how they are assembled.

Vesicle dysfunction is thought to contribute to Alzheimer's disease, diabetes, some hard-to-treat cases of epilepsy, some cancers and immunological disorders and certain neurovascular conditions.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are lipid bilayer-delimited particles produced by all domains of life including complex eukaryotes, both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, mycobacteria, and fungi.

[7][8] Different types of EVs may be separated based on density[9]: Table 1 (by gradient differential centrifugation), size, or surface markers.

[12] However, EV subtypes have an overlapping size and density ranges, and subtype-unique markers must be established on a cell-by-cell basis.

[8] In humans, endogenous extracellular vesicles likely play a role in coagulation, intercellular signaling and waste management.

These EVs contain varied cargo, including nucleic acids, toxins, lipoproteins and enzymes and have important roles in microbial physiology and pathogenesis.

Vesicles carrying DNA from diverse bacteria are abundant in coastal and open-ocean seawater samples.

These primordial biological catalysis were considered to be contained within vesicles (protocells) with membranes composed of fatty acids and related amphiphiles.

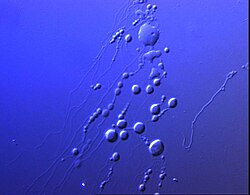

In cyanobacteria, natural selection has worked to create vesicles that are at the maximum diameter possible while still being structurally stable.

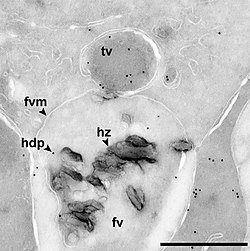

[21] These cell-derived vesicles are specialized to initiate biomineralisation of the matrix in a variety of tissues, including bone, cartilage and dentin.

During normal calcification, a major influx of calcium and phosphate ions into the cells accompanies cellular apoptosis (genetically determined self-destruction) and matrix vesicle formation.

Calcium-loading also leads to formation of phosphatidylserine:calcium:phosphate complexes in the plasma membrane mediated in part by a protein called annexins.

These processes are precisely coordinated to bring about, at the proper place and time, mineralization of the tissue's matrix unless the Golgi are non-existent.

The cell botanist Natasha Raikhel has done some of the basic research in this area, including Zheng et al 1999 in which she and her team found AtVTI1a to be essential to Golgi⇄vacuole transport.

Big fragments of the crushed cells can be discarded by low-speed centrifugation and later the fraction of the known origin (plasmalemma, tonoplast, etc.)

A variety of methods exist to encapsulate biological reactants like protein solutions within such vesicles, making GUVs an ideal system for the in vitro recreation (and investigation) of cell functions in cell-like model membrane environments.