Liquidity trap

"[1] A liquidity trap is caused when people hold cash because they expect an adverse event such as deflation, insufficient aggregate demand, or war.

In which case, as Minsky had stated elsewhere,[8]The view that the liquidity-preference function is a demand-for-money relation permits the introduction of the idea that in appropriate circumstances the demand for money may be infinitely elastic with respect to variations in the interest rate… The liquidity trap presumably dominates in the immediate aftermath of a recession or financial crisis.In the wake of the Keynesian revolution in the 1930s and 1940s, various neoclassical economists sought to minimize the effect of liquidity-trap conditions.

[note 4] In recent times, when the Japanese economy fell into a period of prolonged stagnation, despite near-zero interest rates, the concept of a liquidity trap returned to prominence.

[note 5] Some economists, such as Nicholas Crafts, have suggested a policy of inflation-targeting (by a central bank that is independent of the government) at times of prolonged, very low, nominal interest-rates, in order to avoid a liquidity trap or escape from it.

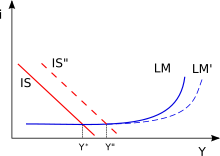

[15] Keynesian economists, like Brad DeLong and Simon Wren-Lewis, maintain that the economy continues to operate within the IS-LM model, albeit an "updated" one,[16] and the rules have "simply changed.

[20] U.S. Federal Reserve economists assert that the liquidity trap can explain low inflation in periods of vastly increased central bank money supply.

[21] This hoarding effect is purported to have reduced consequential inflation to half of what would be expected directly from the increase in the money supply, based on statistics from the expansive years.

[24] Taking the precedent of the 2007–2008 financial crisis, critics[25] of the mainstream definition of a liquidity trap point out that the central bank of the United States never, effectively, lost control of the interest rate.