Lithuanian mythology

Original Lithuanian oral tradition partially survived in national ritual and festive songs and legends which started to be written down in the 18th century.

The first bits about Baltic religion were written down by Herodotus describing Neuri (Νευροί)[1] in his Histories and Tacitus in his Germania mentioned Aestii wearing boar figures and worshipping Mother of gods.

12th century Muslim geographer al-Idrisi in The Book of Roger mentioned Balts as worshipers of Holy Fire and their flourishing city Madsun (Mdsūhn, Mrsunh, Marsūna).

[2] The first recorded Baltic myth - The Tale of Sovij was detected as the complementary insert in the copy of Chronographia (Χρονογραφία) of Greek chronicler from Antioch John Malalas rewritten in the year 1262 in Lithuania.

One of the first valuable sources is the Treaty of Christburg, 1249, between the pagan Prussian clans, represented by a papal legate, and the Teutonic Knights.

In it worship of Kurkas (Curche), the god of harvest and grain, pagan priests (Tulissones vel Ligaschones), who performed certain rituals at funerals are mentioned.

[5][page needed] Chronicon terrae Prussiae is a major source for information on the Order's battles with Old Prussians and Lithuanians.

The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle, which covers the period 1180 – 1343, contains records about ethical codex of the Lithuanians and the Baltic people.

French theologian and cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church, Pierre d'Ailly mentions the Sun (Saulė) as one of the most important Lithuanian gods, which rejuvenates the world as its spirit.

He mentioned also Christian missionaries cutting off holy groves and oaks, which Lithuanians believed to be homes of the gods.

[8] Jan Łasicki created De diis Samagitarum caeterorumque Sarmatarum et falsorum Christianorum (Concerning the gods of Samagitians, and other Sarmatians and false Christians) - written c. 1582 and published in 1615, although it has some important facts it also contains many inaccuracies, as he did not know Lithuanian and relied on stories of others.

Matthäus Prätorius in his two-volume Deliciae Prussicae oder Preussische Schaubühne, written in 1690, collected facts about Prussian and Lithuanian rituals.

The book included a list of Prussian gods, sorted in a generally descending order from sky to earth to underworld and was and important source for reconstructing Baltic and Lithuanian mythology.

The Pomesanian statute book of 1340, the earliest attested document of the customary law of the Balts, as well as the works of Dietrich of Nieheim (Cronica) and Sebastian Münster (Cosmographia).

In the beginning of the 20th century Michał Pius Römer noted - "Lithuanian folklore culture having its sources in heathenism is in complete concord with Christianity".

[10] In 1883, Edmund Veckenstedt published a book Die Mythen, Sagen und Legenden der Zamaiten (Litauer) (English: The myths, sagas and legends of the Samogitians (Lithuanians)).

Feminine gods such as Žemyna (goddess of the earth) are attributed to pre-Indo-European tradition,[16] whereas very expressive thunder-god Perkūnas is considered to derive from Indo-European religion.

It relates to ancient Greek Zeus (Ζευς or Δίας), Latin Dius Fidius,[18] Luvian Tiwat, German Tiwaz.

It closely relates to other thunder gods in many Indo-European mythologies: Vedic Parjanya, Celtic Taranis, Germanic Thor, Slavic Perun.

The Finnic and Mordvin/Erza thunder god named Pur'ginepaz shows in folklore themes that resemble the imagery of Lithuanian Perkunas.

Two well-accepted descendants of the Divine Twins, the Vedic Aśvins and the Lithuanian Ašvieniai, are linguistic cognates ultimately deriving from the Proto-Indo-European word for the horse, *h₁éḱwos.

They are related to Sanskrit áśva and Avestan aspā (from Indo-Iranian *aćua), and to Old Lithuanian ašva, all sharing the meaning of "mare".

The system of polytheistic beliefs is reflected in Lithuanian tales, such as Jūratė and Kastytis, Eglė the Queen of Serpents and the Myth of Sovij.

The earlier confrontational approach to the pre-Christian Lithuanian heritage among common people was abandoned, and attempts were made to use popular beliefs in missionary activities.

The last period of Lithuanian mythology began in the 19th century, when the importance of the old cultural heritage was admitted, not only by the upper classes, but by the nation more widely.

The mythical stories of this period are mostly reflections of the earlier myths, considered not as being true, but as the encoded experiences of the past.

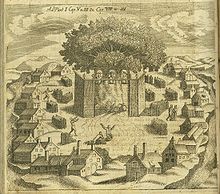

[53] Jerome of Prague was an ardent missionary in Lithuania, leading the chopping of the holy groves and desecration of Lithuanian sacred heathen places.

Mėnulis (Moon) married Saulė (Sun) and they had seven daughters: Aušrinė (Morning Star – Venus), Vakarinė (Evening Star – Venus), Indraja (Jupiter), Vaivora or son Pažarinis in some versions (Mercury), Žiezdrė (Mars), Sėlija (Saturn), Žemė (Earth).

[56] Zodiac or Astrological signs were known as liberators of the Saulė (Sun) from the tower in which it was locked by the powerful king – the legend recorded by Jerome of Prague in 14-15th century.

[50]: 226 Legends (padavimai, sakmės) are a short stories explaining the local names, appearance of the lakes and rivers, other notable places like mounds or big stones.