Little Boy

Little Boy was a type of atomic bomb created by the United States as part of the Manhattan Project during World War II.

Calculations in mid-1942 by theoretical physicists working on the project reinforced the idea that an ordinary artillery gun barrel would be able to impart sufficient velocity to the fissile material projectile.

The belief that the gun design would be an easy engineering task once fuel was available led to a sense of optimism at Los Alamos, although Oppenheimer established a small research group to study implosion as a fallback in early 1943.

[8] A full ordnance program for gun-design development was established by March 1943, with expertise provided by E.L. Rose, an experienced gun designer and engineer.

Oppenheimer led aspects of the effort, telling Rose that "at the present time [May 1945] our estimates are so ill founded that I think it better for me to take responsibility for putting them forward."

He soon delegated the work to Naval Captain William Sterling Parsons, who, along with Ed McMillan, Charles Critchfield, and Joseph Hirschfelder would be responsible for rendering the theory into practice.

To achieve high projectile velocities, the plutonium gun was 17 feet (5.2 m) long with a narrow diameter (suggesting its codename as the Thin Man) which created considerable difficulty in its ballistics dropping from aircraft and fitting it into the bomb bay of a B-29.

If reactor-bred plutonium was used in a gun-type design, they concluded, it would predetonate, causing the weapon to destroy itself before achieving the conditions for a large-scale explosion.

While there was at least one prominent scientist (Ernest O. Lawrence) who advocated for a full-scale test, by early 1945 Little Boy was regarded as nearly a sure thing and was expected to have a higher yield than the first-generation implosion bombs.

Should the bomber carrying the device crash, the hollow "bullet" could be driven into the "target" cylinder, possibly detonating the bomb from gravity alone (though tests suggested this was unlikely), but easily creating a critical mass that would release dangerous amounts of radiation.

[21] If immersed in water, the uranium components were subject to a neutron moderator effect, which would not cause an explosion but would release radioactive contamination.

[20] Ultimately, Parsons opted to keep the explosives out of the Little Boy bomb until after the B-29 had taken off, to avoid the risk of a crash that could destroy or damage the military base from which the weapon was launched.

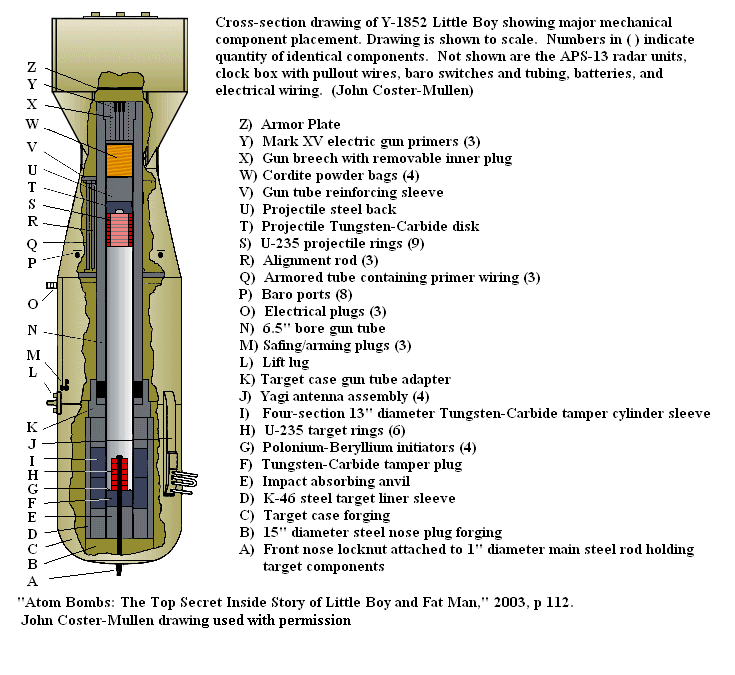

[31][32] A hole in the center of the larger piece dispersed the mass and increased the surface area, allowing more fission neutrons to escape, thus preventing a premature chain reaction.

[33] For the first fifty years after 1945, every published description and drawing of the Little Boy mechanism assumed that a small, solid projectile was fired into the center of a larger, stationary target.

It was dropped over the sea near Tinian in order to test the radar altimeter by the B-29 later known as Big Stink, piloted by Colonel Paul W. Tibbets, the commander of the 509th Composite Group.

The B-29 Next Objective, piloted by Major Charles W. Sweeney, flew to Iwo Jima, where emergency procedures for loading the bomb onto a standby aircraft were practiced.

This rehearsal was repeated on 31 July, but this time L-6 was reloaded onto a different B-29, Enola Gay, piloted by Tibbets, and the bomb was test dropped near Tinian.

[37][38] Parsons, the Enola Gay's weaponeer, was concerned about the possibility of an accidental detonation if the plane crashed on takeoff, so he decided not to load the four cordite powder bags into the gun breech until the aircraft was in flight.

After takeoff, Parsons and his assistant, Second Lieutenant Morris R. Jeppson, made their way into the bomb bay along the narrow catwalk on the port side.

Before climbing to altitude on approach to the target, Jeppson switched the three safety plugs between the electrical connectors of the internal battery and the firing mechanism from green to red.

Data had been collected by Luis Alvarez, Harold Agnew, and Lawrence H. Johnston on the instrument plane, The Great Artiste, but this was not used to calculate the yield at the time.

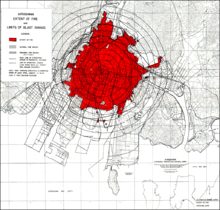

[50] In Hiroshima, almost everything within 1.0 mile (1.6 km) of the point directly under the explosion was completely destroyed, except for about 50 heavily reinforced, earthquake-resistant concrete buildings, only the shells of which remained standing.

[52] A major effect of this kind of structural damage was that it created fuel for fires that were started simultaneously throughout the severe destruction region.

Twenty minutes after the detonation, these fires had merged into a firestorm, pulling in surface air from all directions to feed an inferno which consumed everything flammable.

[58] The Manhattan Project report on Hiroshima estimated that 60% of immediate deaths were caused by fire, but with the caveat that "many persons near the center of explosion suffered fatal injuries from more than one of the bomb effects.

[66][67][68] After the surrender of Japan was finalized, Manhattan Project scientists began to immediately survey the city of Hiroshima to better understand the damage, and to communicate with Japanese physicians about radiation effects in particular.

[70] After hostilities ended, a survey team from the Manhattan Project that included William Penney, Robert Serber, and George T. Reynolds was sent to Hiroshima to evaluate the effects of the blast.

[73] A review conducted by a scientist at Los Alamos in 1985 concluded, on the basis of existing blast, thermal, and radiological data, and then-current models of weapons effects, that the best estimate of the yield was 15 kilotons of TNT (63 TJ) with an uncertainty of 20% (±3 kt).

[77][78] At Sandia Base, three Army officers, Captains Albert Bethel, Richard Meyer, and Bobbie Griffin attempted to re-create the Little Boy.

They were supervised by Harlow W. Russ, an expert on Little Boy who served with Project Alberta on Tinian, and was now leader of the Z-11 Group of the Los Alamos Laboratory's Z Division at Sandia.