Lobotomy

Ominous portrayals of lobotomized patients in novels, plays, and films further diminished public opinion, and the development of antipsychotic medications led to a rapid decline in lobotomy's popularity and Freeman’s reputation.

These novel remedial methodologies, however, meant that (at the time) modern psychiatric treatments were no longer relegated to the metaphysical or abstract, and this increased the popularity of the field among clinicians and prospective patients alike.

[32] Additionally, the relative (and quantitative) success of the shock therapies, despite the considerable risks they posed to patients, also helped to inspire doctors in the field to pioneer ever more drastic forms of medical interventions up to, and including, lobotomies.

[35] Many doctors, patients, and family members of the period believed that despite potentially catastrophic consequences, the results of lobotomy were seemingly positive in many instances or, were at least deemed as such when measured next to the apparent alternative of long-term institutionalisation.

[40] Intending to ameliorate symptoms in those with violent and intractable conditions rather than effect a cure,[41] Burckhardt began operating on patients in December 1888,[42] but both his surgical methods and instruments were crude and the results of the procedure were mixed at best.

[46] In 1912, two physicians based in Saint Petersburg, the leading Russian neurologist Vladimir Bekhterev and his younger Estonian colleague, the neurosurgeon Ludvig Puusepp, published a paper reviewing a range of surgical interventions that had been performed on the mentally ill.[47] While generally treating these endeavours favorably, in their consideration of psychosurgery they reserved unremitting scorn for Burckhardt's surgical experiments of 1888 and opined that it was extraordinary that a trained medical doctor could undertake such an unsound procedure.

[63] At the 1935 Congress, with Moniz in attendance,[n 8] Fulton and Jacobsen presented two chimpanzees, named Becky and Lucy who had had frontal lobectomies and subsequent changes in behaviour and intellectual function.

[64] According to Fulton's account of the congress, they explained that before surgery, both animals, and especially Becky, the more emotional of the two, exhibited "frustrational behaviour" – that is, have tantrums that could include rolling on the floor and defecating – if, because of their poor performance in a set of experimental tasks, they were not rewarded.

[65] Following the surgical removal of their frontal lobes, the behaviour of both primates changed markedly and Becky was pacified to such a degree that Jacobsen apparently stated it was as if she had joined a "happiness cult".

[66] Moniz began his experiments with leucotomy just three months after the congress had reinforced the apparent cause-and-effect relationship between the Fulton and Jacobsen presentation and the Portuguese neurologist's resolve to operate on the frontal lobes.

[68] Endorsing this version of events, in 1949, the Harvard neurologist Stanley Cobb remarked during his presidential address to the American Neurological Association that "seldom in the history of medicine has a laboratory observation been so quickly and dramatically translated into a therapeutic procedure".

[69] In fact, Moniz stated that he had conceived of the operation sometime before his journey to London in 1935, having told in confidence his junior colleague, the young neurosurgeon Pedro Almeida Lima, as early as 1933 of his psychosurgical idea.

The refinement of neurosurgical techniques also facilitated increasing attempts to remove brain tumours, and treat focal epilepsy in humans and led to more precise experimental neurosurgery in animal studies.

[73] In 1922, the Italian neurologist Leonardo Bianchi published a detailed report on the results of bilateral lobectomies in animals that supported the contention that the frontal lobes were both integral to intellectual function and that their removal led to the disintegration of the subject's personality.

[n 9][75] The neurologist Richard Brickner reported on this case in 1932,[76] relating that the recipient, known as "Patient A", while experiencing a blunting of affect, had no apparent decrease in intellectual function and seemed, at least to the casual observer, perfectly normal.

[82] Although ultimately discounting brain surgery as carrying too much risk, physicians and neurologists such as William Mayo, Thierry de Martel, Richard Brickner, and Leo Davidoff had, before 1935, entertained the proposition.

[86] In Switzerland, almost simultaneously with the commencement of Moniz's leucotomy programme, the neurosurgeon François Ody had removed the entire right frontal lobe of a catatonic schizophrenic patient.

[61] He differed significantly from Burckhardt, however in that he did not think there was any organic pathology in the brains of the mentally ill, but rather that their neural pathways were caught in fixed and destructive circuits leading to "predominant, obsessive ideas".

[94] Unlike the position adopted by Burckhardt, it was unfalsifiable according to the knowledge and technology of the time as the absence of a known correlation between physical brain pathology and mental illness could not disprove his thesis.

[95] The hypotheses underlying the procedure might be called into question; the surgical intervention might be considered very audacious; but such arguments occupy a secondary position because it can be affirmed now that these operations are not prejudicial to either physical or psychic life of the patient, and also that recovery or improvement may be obtained frequently in this way.

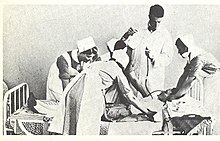

[97] The initial patients selected for the operation were provided by the medical director of Lisbon's Miguel Bombarda Mental Hospital, José de Matos Sobral Cid.

[101] To this end, it was decided that Lima would trephine into the side of the skull and then inject ethanol into the "subcortical white matter of the prefrontal area"[96] so as to destroy the connecting fibres, or association tracts,[102] and create what Moniz termed a "frontal barrier".

[109] Complications were observed in each of the leucotomy patients and included: "increased temperature, vomiting, bladder and bowel incontinence, diarrhea, and ocular affections such as ptosis and nystagmus, as well as psychological effects such as apathy, akinesia, lethargy, timing, and local disorientation, kleptomania, and abnormal sensations of hunger".

[115] Nonetheless, Moniz's reported successful surgical treatment of 14 out of 20 patients led to the rapid adoption of the procedure on an experimental basis by individual clinicians in countries such as Brazil, Cuba, Italy, Romania and the United States during the 1930s.

[55] In 1937, he was invited to Italy to demonstrate the procedure and for two weeks in June of that year, he visited medical centres in Trieste, Ferrara, and one close to Turin – the Racconigi Hospital – where he instructed his Italian neuropsychiatric colleagues on leucotomy and also oversaw several operations.

[122] Fiamberti's method was to puncture the thin layer of orbital bone at the top of the socket and then inject alcohol or formalin into the white matter of the frontal lobes through this aperture.

[128] Freeman, who favoured an organic model of mental illness causation, spent the next several years exhaustively, yet ultimately fruitlessly, investigating a neuropathological basis for insanity.

A large proportion of such lobotomized patients exhibited reduced tension or agitation, but many also showed other effects, such as apathy, passivity, lack of initiative, poor ability to concentrate, and a generally decreased depth and intensity of their emotional response to life.

"[151] In 1948 Norbert Wiener, the author of Cybernetics: Or the Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, said: "Prefrontal lobotomy... has recently been having a certain vogue, probably not unconnected with the fact that it makes the custodial care of many patients easier.

[156] In 1977, the US Congress, during the presidency of Jimmy Carter, created the National Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research to investigate allegations that psychosurgery – including lobotomy techniques – was used to control minorities and restrain individual rights.