Logical biconditional

[2][3] Nowadays, notations to represent equivalence include

, and the XNOR (exclusive nor) Boolean operator, which means "both or neither".

Semantically, the only case where a logical biconditional is different from a material conditional is the case where the hypothesis (antecedent) is false but the conclusion (consequent) is true.

In this case, the result is true for the conditional, but false for the biconditional.

In other words, the sets P and Q coincide: they are identical.

When phrased as a sentence, the antecedent is the subject and the consequent is the predicate of a universal affirmative proposition (e.g., in the phrase "all men are mortal", "men" is the subject and "mortal" is the predicate).

means that P implies Q and Q implies P; in other words, the propositions are logically equivalent, in the sense that both are either jointly true or jointly false.

Again, this does not mean that they need to have the same meaning, as P could be "the triangle ABC has two equal sides" and Q could be "the triangle ABC has two equal angles".

When an implication is translated by a hypothetical (or conditional) judgment, the antecedent is called the hypothesis (or the condition) and the consequent is called the thesis.

A common way of demonstrating a biconditional of the form

separately (due to its equivalence to the conjunction of the two converse conditionals[2]).

When both members of the biconditional are propositions, it can be separated into two conditionals, of which one is called a theorem and the other its reciprocal.

[citation needed] Thus whenever a theorem and its reciprocal are true, we have a biconditional.

When a theorem and its reciprocal are true, its hypothesis is said to be the necessary and sufficient condition of the thesis.

That is, the hypothesis is both the cause and the consequence of the thesis at the same time.

Notations to represent equivalence used in history include: and so on.

[citation needed][vague][clarification needed] Logical equality (also known as biconditional) is an operation on two logical values, typically the values of two propositions, that produces a value of true if and only if both operands are false or both operands are true.

For example, the statement may be interpreted as or may be interpreted as saying that all xi are jointly true or jointly false: As it turns out, these two statements are only the same when zero or two arguments are involved.

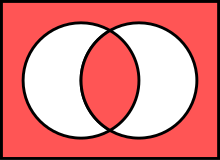

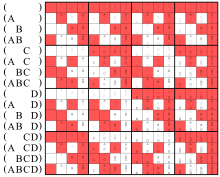

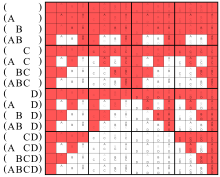

In fact, the following truth tables only show the same bit pattern in the line with no argument and in the lines with two arguments: The left Venn diagram below, and the lines (AB ) in these matrices represent the same operation.

Red areas stand for true (as in for and).

Walsh spectrum: (2,0,0,2) Nonlinearity: 0 (the function is linear) Like all connectives in first-order logic, the biconditional has rules of inference that govern its use in formal proofs.

Or more schematically: One unambiguous way of stating a biconditional in plain English is to adopt the form "b if a and a if b"—if the standard form "a if and only if b" is not used.

The plain English "if'" may sometimes be used as a biconditional (especially in the context of a mathematical definition[15]).

In which case, one must take into consideration the surrounding context when interpreting these words.

For example, the statement "I'll buy you a new wallet if you need one" may be interpreted as a biconditional, since the speaker doesn't intend a valid outcome to be buying the wallet whether or not the wallet is needed (as in a conditional).

(true part in red)

meant as equivalent to

The central Venn diagram below,

and line (ABC ) in this matrix

represent the same operation.

meant as shorthand for

The Venn diagram directly below,

and line (ABC ) in this matrix

represent the same operation.