Port of London

[3] Usage is largely governed by the Port of London Authority ("PLA"), a public trust established in 1908; while mainly responsible for coordination and enforcement[4] of activities it also has some minor operations of its own.

[5] The port can handle cruise liners, roll-on roll-off ferries and cargo of all types at the larger facilities in its eastern extent.

As with many similar historic European ports, such as Antwerp and Rotterdam, many activities have steadily moved downstream towards the open sea as ships have grown larger and the land upriver taken over for other uses.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, it was the busiest port in the world, with wharves extending continuously along the Thames for 11 miles (18 km), and over 1,500 cranes handling 60,000 ships per year.

The lavish nature of goods traded in London shaped the extravagant lifestyle of its citizens and the city flourished under Roman colonization.

In the late 18th century, an ambitious scheme was proposed by Willey Reveley to straighten the Thames between Wapping and Woolwich Reach by cutting a new channel across the Rotherhithe, Isle of Dogs, and Greenwich peninsulas.

Throughout the 19th century, a series of enclosed dock systems was built, surrounded by high walls to protect cargoes from river piracy.

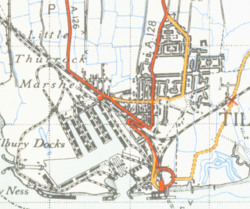

This culminated in expansion of Tilbury in the late 1960s to become a major container port (the UK's largest in the early 1970s), together with a huge riverside grain terminal and mechanised facilities for timber handling.

By 1900, the wharves and docks were receiving about 7.5 million tons of cargo each; an inevitable result of the extending reach of the British Empire.

While most of the dockers were casual labourers, there were skilled stevedores who loaded ships, and lightermen who unloaded cargo from moored boats via barges.

[18] Alongside the docks many port industries developed, some of which (notably sugar refining, edible oil processing, vehicle manufacture and lead smelting) survive today.

Other industries have included iron working, casting of brass and bronze, shipbuilding, timber, grain, cement and paper milling, armament manufacture, etc.

Although by 1930 the number of major dry docks had been reduced to 16, highly mechanised and geared to the repair of iron and steel-hulled ships.

Major Thames-side gasworks were located at Beckton and East Greenwich, with power stations including Brimsdown, Hackney and West Ham on the River Lea and Kingston, Fulham, Lots Road, Wandsworth, Battersea, Bankside, Stepney, Deptford, Greenwich, Blackwall Point, Brunswick Wharf, Woolwich, Barking, Belvedere, Littlebrook, West Thurrock, Northfleet, Tilbury and Grain on the Thames.

The coal requirements of power stations and gas works constituted a large proportion of London's post-war trade.

A 1959 Times article[21] states: About two-thirds of the 20 million tons of coal entering the Thames each year is consumed in nine gas works and 17 generating stations.

For example, Beckton Gas Works had two large piers which dealt with both its own requirements and with the transfer of coal to lighters for delivery to other gasworks.

Trade at privately owned wharves on the open river continued for longer, for example with container handling at the Victoria Deep Water Terminal on the Greenwich Peninsula into the 1990s, and bulk paper import at Convoy's Wharf in Deptford until 2000.

The wider port continued to be a major centre for trade and industry, with oil and gas terminals at Coryton, Shell Haven and Canvey in Essex and the Isle of Grain in Kent.

[23] These are mainly concentrated at Purfleet (with the world's largest margarine works), Thurrock, Tilbury (the Port's current main container facility), London Gateway, Coryton and Canvey Island in Essex, Dartford and Northfleet in Kent, and Greenwich, Silvertown, Barking, Dagenham and Erith in Greater London.

At Silvertown, for example, Tate & Lyle continues to operate the world's largest cane sugar refinery, originally served by the West India Docks but now with its own cargo handling facilities.

Local authorities are contributing to this increase in intraport traffic, with waste transfer and demolition rubble being taken by barges on the river.

[28] The Crossrail project alone involved the transporting of 5 million tonnes of material, almost all of which is clean earth, excavated from the ground, downstream through the Port, from locations such as Canary Wharf to new nature reserves being constructed in the Thames estuary area.