Los caprichos

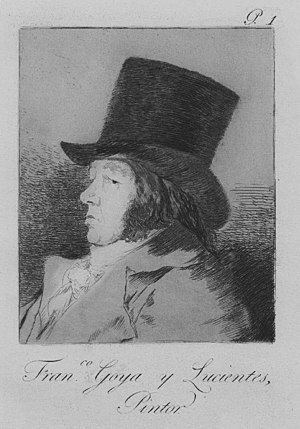

Los Caprichos (The Caprices) is a set of 80 prints in aquatint and etching created by the Spanish artist Francisco Goya in 1797–1798 and published as an album in 1799.

Goya explained in an announcement that he chose subjects "from the multitude of faults and vices common in every civil society, as well as from the vulgar prejudices and lies authorized by custom, ignorance or self-interest, those that he has thought most suitable matter for ridicule".

The series was published in February 1799; however, just 14 days after going on sale, when Manuel Godoy and his affiliates lost power, the painter hastily withdrew the copies still available for fear of the Inquisition.

In 1807, to save the Caprichos, Goya decided to offer the king the plates and the 240 unsold copies, destined for the Royal Calcography, in exchange for a lifetime pension of twelve thousand reales per year for his son Javier.

Los Caprichos have influenced generations of artists from movements as diverse as French Romanticism, Impressionism, German Expressionism or Surrealism.

Ewan MacColl and André Malraux considered Goya one of the precursors of modern art, citing the innovations and ruptures of the Caprichos.

After the coronation of Charles IV, Goya portrayed the king with his wife, Queen María Luisa, subsequently being named Court Painter.

To convalesce, he was taken to Cádiz to the home of his enlightened friend Sebastián Martínez, availing of the good doctors of the Faculty and the benevolent climate of the city.

He referred to innovative small paintings of themes related to the Inquisition or the asylum where he had developed a personal and intense vision with an extremely expressive style.

In 1796 Goya returned to Andalusia with Ceán Bermúdez, and after July he was in Sanlúcar de Barrameda with the Duchess of Alba, who had been widowed the previous month.

[14] Goya initially conceived this series of prints as "Sueños" (Dreams) (and not as Caprichos), making at least 28 preparatory drawings, 11 of them from Album B (in the Prado Museum except for some that have disappeared).

For instance, the royal collections contained the works of Hieronymus Bosch, whose strange creatures were surely men and women whose vices had turned them into animals that represented their defects.

[25] According to the advertisement in Diario Madrid, Goya intended to imitate literature on censorship and human vices; an entire aesthetic, sociological, and moral program is reflected in the motives of his work.

[18] The fear of the Inquisition, which then enforced public morality and sustained the existing society, was real, since these engravings attacked the clergy and the high nobility.

In 1803, to save the Caprichos, Goya decided to offer the plates and all the available series (240) to the king, destined for the Royal Chalcography, in exchange for a pension for his son.

Two others, one that belonged to the playwright López de Ayala and the other in the National Library of Madrid, contain language that freely criticizes the clergy, politics, and even specific people.

In a radically new way, he showed a materialist and dispassionate vision, in contrast to the paternalistic social criticism carried out in the 18th century that directed its efforts to reform the erroneous behavior of man.

In the second part he shows fantastic engravings where he abandoned the rational point of view, and following the logic of the absurd, he painted delirious visions with strange beings.

López Rey believed that in this part the evil in Los Caprichos is reduced to the absurd, drawing the demonic as the result of man's error in separating himself from the ways of reason.

Goya in the Witchcrafts satirizes his personal conclusions over feminine inconstancy and the censorship of social vices, now believing in the existence of evil that he expresses in beings of repulsive ugliness.

According to the Ayala and National Library manuscripts that interpret the Caprichos, Goya's intention would be to point out that the true goblins are the priests and friars who eat and drink at our expense and who outstretch their hands to take.

The differences between the two are pointed out by M. Paul-André Lemoisne: Rembrandt mastered the craft of an engraver, usually beginning his sketches directly on the plate, just as painter-engravers do.

All the advantages of drawing of forming physiognomies, twisting gestures, and distorting features that are easy to do with the pencil are systematically repeated in engraving with the burin.

The manuscript called “Ayala,” owned by that playwright, is perhaps the oldest and least discreet because it does not hesitate to point out professional groups or specific people, such as the queen or Godoy, as objects of the satire.

Cardedera, the first collector of his graphic work, thought that the Royal Calcography was considering printing the Prado’s explanation along with the engravings, but did not do so because the commentary openly criticized the vices of the Court.

[58] Although Goya emphasized his interest in the universal and the absence of specific criticism, since publication of the Caprichos an attempt has been made to place the satire in the political climate of his time, resulting in speculation personalizing the figures to Queen María Luisa; Godoy; Carlos IV; Urquijo; Morla; the duchesses of Alba, Osuna and Benavente; etc.

The artist reinforces the satire with the hammer blow of the title "Hasta la muerte" (Until death), a devastating sarcasm that completes the scenario.

His article on the Caprichos was published in Le Present (1857), in L'Artiste (1858) and in the collection Curiosités Esthétiques (1868):[65] Goya's romantic image passed from France to England, while it remained in Spain.

The attraction of Goya's emotional content on the artists and critics of Expressionism at the beginning of the 20th century influenced Nolde, Max Beckmann, Franz Marc, and especially Paul Klee.

[56] As Sánchez Cantón points out in his book on the Caprichos, knowledge of their preparation and the environment in which they were created will enhance enjoyment, hidden or obscure aspects may be examined, and their value as historical documents noted.

Drawing from Album A of the Duchess combing her hair. Chinese ink wash.

In principle, Goya planned this Capricho to be the cover of his engravings. Here he portrayed himself in a very different way than he finally decided to present himself at the beginning of Los Caprichos : abstracted, half asleep, and surrounded by his obsessions. An owl hands him his drawing supplies, clearly indicating the origin of his inventions. He intended the cover title as: " Dreams, the First Universal Language. Drawn and engraved by Francisco de Goya. Year 1797. The Author Dreaming ." His aim is to banish harmful vulgarities, and with this work of Caprichos promulgate the solid testimony of the truth." [ 16 ]

The Inquisition understood that the caption referred, not to the prisoner as it seems at first glance, but to the court. For this reason, the work was denounced to the Inquisition.