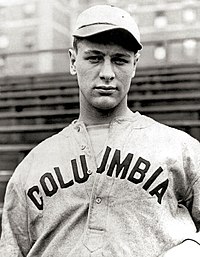

Lou Gehrig

Gehrig was an All-Star seven consecutive times,[2] a Triple Crown winner once,[3] an American League (AL) Most Valuable Player twice[3] and a member of six World Series champion teams.

In 1969, the Baseball Writers' Association of America voted Gehrig the greatest first baseman of all time,[11] and he was the leading vote-getter on the MLB All-Century Team chosen by fans in 1999.

Henry Louis Gehrig[13] was born June 19, 1903, at 1994 Second Avenue in the East Harlem neighborhood of New York City;[14] he weighed almost 14 pounds (6.4 kg) at birth.

[15][16] Gehrig's father was a sheet-metal worker by trade who was frequently unemployed due to alcoholism and epilepsy, and his mother, a maid, was the main breadwinner and disciplinarian in their family.

[27] With his team leading 8–6 in the top of the ninth inning, Gehrig hit a grand slam completely out of the major league park, which was an unheard-of feat for a 17-year-old.

Before his first semester began, New York Giants manager John McGraw advised Gehrig to play summer professional baseball under an assumed name, Henry Lewis, despite the fact that it could jeopardize his collegiate sports eligibility.

Only a handful of collegians were at Columbia's South Field that day, but more significant was the presence of New York Yankees scout Paul Krichell, who had been trailing Gehrig for some time.

Except for his games at Hartford, a two-hour car ride away, Gehrig would play his entire baseball life—sandlot, high school, college and professional—with teams based in New York City.

[30] Gehrig's production helped the 1927 Yankees to a 110–44 record, the AL pennant (by nineteen games) and a four-game sweep of the Pittsburgh Pirates in the World Series.

Although the AL recognized his season by naming him league MVP, Gehrig's accomplishments were overshadowed by Ruth's record-breaking sixty home runs and the overall dominance of the 1927 Yankees, a team often cited as having the greatest lineup of all time, the famed "Murderers' Row.

[41] He narrowly missed hitting a fifth home run when Athletics center fielder Al Simmons made a leaping catch of another fly ball at the center-field fence.

"[47] Producer Sol Lesser was unimpressed with Gehrig's legs, calling them "more functional than decorative," and passed on him for the role which eventually went to the 1936 Olympic decathlon gold medalist Glenn Morris.

For example: In addition, x-rays taken late in his life disclosed that Gehrig had sustained several fractures during his playing career, although he remained in the lineup despite those previously undisclosed injuries.

[52] However, the streak was helped when Yankees general manager Ed Barrow postponed a game as a rainout on a day when Gehrig was sick with the flu, though it was not raining.

However, with Gehrig hitless in five of the eight games, McCarthy found himself resisting pressure from Yankee management to switch his slumping player to a part-time role.

[64] The prognosis was grim: rapidly increasing paralysis, difficulty in swallowing and speaking and a life expectancy less than three years, although no impairment of mental functions would occur.

Gehrig's wife was told that the cause of the disease was unknown, but that it was painless, not contagious and cruel; the motor function of the central nervous system is destroyed, but the mind remains fully aware until the end.

[65][66] Gehrig often wrote letters to his wife, and one such note written shortly after the diagnosis said in part: The bad news is lateral sclerosis, in our language "creeping" paralysis.

Playing is out of the question ...[67]Following Gehrig's diagnosis, he briefly rejoined the Yankees in Washington, D.C. As his train pulled into Union Station, he was greeted by a group of Boy Scouts happily waving and wishing him luck.

"[15][68] Although Gehrig's symptoms were consistent with ALS and he did not experience the wild mood swings and eruptions of uncontrolled violence that define chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), an article in the September 2010 issue of the Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology[69] suggested the possibility that some ALS-related illnesses diagnosed in Gehrig and other athletes may have been CTE, catalyzed by repeated concussions and other brain trauma.

[70][71] In 2012, Minnesota state representative Phyllis Kahn sought to change the law protecting the privacy of Gehrig's medical records, which are held by the Mayo Clinic, in an effort to determine if a connection could exist between his illness and the concussion-related trauma that he had received during his career.

[75] In its coverage the following day, The New York Times wrote that the ceremony was "perhaps as colorful and dramatic a pageant as ever was enacted on a baseball field [as] 61,808 fans thundered a hail and farewell.

New York mayor Fiorello La Guardia called Gehrig the "perfect prototype of the best sportsmanship and citizenship" and Postmaster General James Farley concluded his speech by predicting, "Your name will live long in baseball and wherever the game is played they will point with pride and satisfaction to your record.

The Times account the following day called the moment "one of the most touching scenes ever witnessed on a ball field" that made even hard-boiled reporters "swallow hard.

[21] Following the funeral across the street from his house at Christ Episcopal Church of Riverdale, Gehrig's remains were cremated on June 4 at Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York, 21 miles (34 km) north of Yankee Stadium in suburban Westchester County.

[28] Despite playing in the shadow of Ruth for two-thirds of his career, Gehrig was one of the highest run producers in baseball history; he had 509 RBIs during a three-season stretch (1930–32).

[108] Located at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital and Columbia University Irving Medical Center, they have a clinical and research function directed at ALS and the related motor neuron diseases primary lateral sclerosis and progressive muscular atrophy.

[115] In 2006, researchers presented a paper to the American Academy of Neurology, reporting on an analysis of Rawhide and photographs of Gehrig from the 1937–1939 period, to ascertain when he began to show visible symptoms of ALS.

"The Lou Gehrig Story", about the days leading up to his farewell speech, was also featured on an episode of the CBS anthology TV series Climax!

In the top of the ninth, with Sox icon Ted Lyons holding a slim lead, Gehrig came to bat with a man on base, and the elder Shepherd yelled in a voice that echoed around the ballpark, "Hit one up here, ya bum!