Louis Brandeis

have criticized Brandeis for evading issues related to African-Americans, as he did not author a single opinion on any cases about race during his twenty-three year tenure, and he consistently voted with the Supreme Court majority including in support of racial segregation.

[13]: 18 Louis grew up in "a family enamored with books, music, and politics, perhaps best typified by his revered uncle, Lewis Dembitz, a refined, educated man who served as a delegate to the Republican convention in 1860 that nominated Abraham Lincoln for president.

Brandeis easily adapted to the new methods, becoming active in class discussions,[10] and joined the Pow-Wow club, similar to today's moot courts in law school, which gave him experience in the role of a judge.

Soon after, Chief Justice Melville Fuller recommended him to a friend as the best attorney he knew of in the Eastern U.S.[19] Before taking on business clients, he insisted they agree to two major conditions: that he would only deal with the person in charge, never intermediaries, and he could be allowed to advise on any relevant aspects of the firm's affairs.

As a result, many bills pass in our legislatures which would not have become law if the public interest had been fairly represented.... Those of you who feel drawn to that profession may rest assured that you will find in it an opportunity for usefulness probably unequaled.

He spent the next year in studying the workings of the life insurance industry, often writing articles and giving speeches about his findings, at one point describing its practices as "legalized robbery.

[34]: 41–52 In June 1907, Brandeis was asked by Boston and Maine stockholders to present their cause to the public, a case that he again took on by insisting on serving without payment, "leaving him free to act as he thought best."

After months of extensive research, Brandeis published a 70-page booklet in which he argued that New Haven's acquisitions were putting its financial condition in jeopardy, and he predicted that within a few years, it would be forced to cut its dividends or to become insolvent.

At a subsequent hearing in front of the Interstate Commerce Commission in Boston, New Haven's president "admitted that the railroad had maintained a floating slush fund that was used to make 'donations' to politicians who cooperated.

By the spring of 1913, the Department of Justice launched a new investigation, and the next year, the Interstate Commerce Commission charged the New Haven with "extravagance and political corruption and its board of directors with dereliction of duty.

I believe that we are confronted with the profound politico-economic philosophy, matured in the wood for twenty years, of the finest brain and the most powerful personality in the Democratic party, who happens to be a Justice of the Supreme Court.

His brief proved decisive in Muller v. Oregon, the first Supreme Court ruling to accept the legitimacy of a scientific examination of the social conditions, in addition to the legal facts involved in a case.

According to the judicial historian Stephen Powers, the "so-called 'Brandeis Brief' became a model for progressive litigation" by taking into consideration social and historical realities, rather than just the abstract general principles.

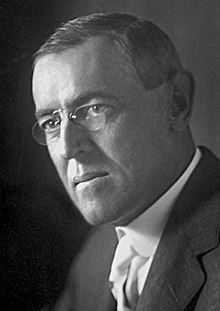

Wilson endorsed Brandeis's proposals and those of Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, both of whom felt that the banking system needed to be democratized and its currency issued and controlled by the government.

[12]: 470 Further opposition came from members of the legal profession, including former Attorney General George W. Wickersham and former presidents of the American Bar Association, such as former Senator and Secretary of State Elihu Root of New York, who claimed Brandeis was "unfit" to serve on the Supreme Court.

He added: I cannot speak too highly of his impartial, impersonal, orderly, and constructive mind, his rare analytical powers, his deep human sympathy, his profound acquaintance with the historical roots of our institutions and insight into their spirit, or of the many evidences he has given of being imbued, to the very heart, with our American ideals of justice and equality of opportunity; of his knowledge of modern economic conditions and of the way they bear upon the masses of the people, or of his genius in getting persons to unite in common and harmonious action and look with frank and kindly eyes into each other's minds, who had before been heated antagonists.

[56][57] Some have criticized Brandeis for having, as a judge, evaded issues related to African-Americans, since he did not author a single opinion on any cases about race during his twenty-three year tenure, and consistently voted with the court majority including in support of racial segregation.

"[64] Legal author Ken Gormley says Brandeis was "attempting to introduce a notion of privacy which was connected in some fashion to the Constitution ... and which worked in tandem with the First Amendment to assure a freedom of speech within the four brick walls of the citizen's residence.

He also first articulated what ultimately came to be known as the unitary business principle, when he wrote for the Court "The profits of the corporation were largely earned by a series of transactions beginning with manufacture in Connecticut and ending with sale in other states.

In their opinion and test to uphold the conviction, they expanded the definition of "clear and present danger" to include the condition that the "evil apprehended is so imminent that it may befall before there is opportunity for full discussion."

According to legal historian Anthony Lewis, scholars have lauded Brandeis's opinion "as perhaps the greatest defense of freedom of speech ever written by a member of the high court.

They did not exalt order at the cost of liberty ...In his widely cited dissenting opinion in Olmstead v. United States (1928), Brandeis relied on thoughts he developed in his 1890 Harvard Law Review article "The Right to Privacy.

The radio can be turned off, but not so the billboard or street car placard.Brandeis forever changed the way people think about stare decisis, one of the most distinctive principles of the common law legal system.

In his widely cited dissenting opinion in Burnet v. Coronado Oil & Gas Co. (1932), Brandeis "catalogued the Court’s actual overruling practices in such a powerful manner that his attendant stare decisis analysis immediately assumed canonical authority.

According to John Vile, in the final years of his career, like the rest of the Court, he "initially combated the New Deal of Franklin D. Roosevelt, which went against everything Brandeis had ever preached in opposition to the concepts of 'bigness' and 'centralization' in the federal government and the need to return to the states.

[10] Economics author John Steele Gordon writes that the National Recovery Administration (NRA) was "the first iteration of Roosevelt's New Deal ... essentially a government-run cartel to fix prices and divide markets ...

Writing for the Court, Brandeis overruled the ninety-six-year-old doctrine of Swift v. Tyson (1842), and held that there was no such thing as a "federal general common law" in cases involving diversity jurisdiction.

He embarked on a speaking tour in the fall and winter of 1914–1915 to garner support for the Zionist cause, emphasizing the goal of self-determination and freedom for Jews through the development of a Jewish homeland.

He explained his belief in the importance of Zionism in a famous speech he gave at a conference of Reform Rabbis in April 1915:[87] The Zionists seek to establish this home in Palestine because they are convinced that the undying longing of Jews for Palestine is a fact of deepest significance; that it is a manifestation in the struggle for existence by an ancient people which has established its right to live, a people whose three thousand years of civilization has produced a faith, culture and individuality which enable it to contribute largely in the future, as it has in the past, to the advance of civilization; and that it is not a right merely but a duty of the Jewish nationality to survive and develop.

Postal Service in September 2009 honored Brandeis by featuring his image on a new set of commemorative stamps along with U.S. Supreme Court associate justices Joseph Story, Felix Frankfurter and William J. Brennan Jr.[100] In the Postal Service announcement about the stamp, he was credited with being "the associate justice most responsible for helping the Supreme Court shape the tools it needed to interpret the Constitution in light of the sociological and economic conditions of the 20th century."