Hubert Lyautey

[3][4] Lyautey was also the first one to use the term "hearts and minds" as part of his strategy to counter the Black Flags rebellion during the Tonkin campaign in 1885.

His mother was a Norman aristocrat, and Lyautey inherited many of her assumptions: monarchism, patriotism, Catholicism and the belief in the moral and political importance of the elite.

He pacified northern and western Madagascar; administered a region of 200,000 inhabitants; began the construction of a new provincial capital at Ankazobe and a new roadway across the island; He encouraged the cultivation of rice, coffee, tobacco, grain, and cotton; and opened schools.

[11] He returned to France to command a cavalry regiment in 1902 before he was promoted to brigade general a year later, largely a result of the military skill and success which he had shown in Madagascar.

The French Foreign Minister issued a vague disavowal of Lyautey because he was concerned at clashing with British influence in Morocco.

[14] In the event, Britain, Spain and Italy were placated by France agreeing to allow them a free hand in Egypt, northern Morocco, and Libya respectively, and the only objections to French expansion in the region came from Germany (see First Moroccan Crisis).

[23] The same day, War Minister Messimy told Lyautey to prepare to abandon Morocco except for the major cities and ports and to send all seasoned troops to France.

[11] Lyautey adopted and emulated Gallieni's policy of methodical expansion of pacified areas followed by social and economical development (markets, schools and medical centres) to bring about the end of resistance and the cooperation of former insurgents.

[30] He tried to balance blunt military force with other means of power and promoted a vision of a better future for the Moroccans under the French colonial administration.

For example, he invited a talented young French urban planner, Henri Prost, to design comprehensive plans for redevelopment of the major Moroccan cities.

[11] Lyautey briefly served as France's Minister of War for three months in 1917, which were clouded by the unsuccessful Nivelle Offensive and the French Army Mutinies.

Lyautey was apparently surprised to receive a telegram offering him the job (10 December 1916) and demanded and was given authority to issue orders to Nivelle (the new Commander-in-Chief of French forces on the Western Front) and Sarrail (Commander-in-Chief at Salonika); Nivelle's predecessor Joffre had enjoyed much greater freedom from the War Minister and had also had command over Salonika.

Prime Minister Aristide Briand, not going into detail about Joffre's removal, replied that Lyautey would be one of a War Committee of five members, controlling manufacturing, transport and supply, and thus giving him greater powers than his predecessors.

Lyautey had hoped to rely on Joffre, Ferdinand Foch and de Castelnau, but the first soon resigned from his job as advisor, Foch had already been sacked as commander of Army Group North, de Castelnau was sent on a mission to Russia, and Lyautey was not permitted to revive the post of Chief of the Army General Staff.

On the train to the Rome Conference (5–6 January 1917) Lyautey stood before a map lecturing the British delegation on their Palestine campaign.

He wrote to the King’s adviser Clive Wigram (12 January): Lyautey … is a dried up person of the Anglo-Indian type who has been in the colonies all his life and talks of nothing else.

[38]Lyautey attended the infamous Calais Conference on 27 February 1917, at which Lloyd George attempted to subordinate British forces in France to Nivelle.

He contemplated trying to have Nivelle dismissed but backed down in the face of traditional republican hostility to military men with political aspirations.

[46] During the First World War, he had insisted on the continuation of the occupation of the whole country regardless of the fact that France needed most of her resources in the struggle against the Central Powers.

He resigned in 1925, feeling slighted that Paris had appointed Philippe Pétain to command 100,000 men to put down Abd-el-Krim’s rebellion in the Rif Mountains.

[12] Political opposition in Paris ensured that he received no official recognition when he resigned; his only escort home was two destroyers of the Royal Navy.

[50] The same year he contributed to the effort to warn French people against Hitler through a critical introduction of an unauthorised edition of Mein Kampf.

Lyautey would have liked to have been a national saviour; he was disappointed to have played only a minor role in France's political life and in the First World War.

"[53] Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau – whom Lyautey despised, as he did most politicians – is quoted as having said: Here is an admirable and courageous man who always had balls up to his ass.

[54]It has been speculated that Lyautey might have provided Marcel Proust with the model for the character of the homosexual Baron de Charlus in his magnum opus Remembrance of Things Past.

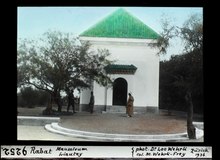

Following his resignation from the position of Resident-general in 1925, Lyautey planned for his own burial in Rabat and in 1933 requested painter Joseph de La Nézière to produce a sketch for his mausoleum as a traditional Muslim Qubba.

Even so, the erection of a monument to Morocco's Christian colonizer was controversial and criticized by Mohamed Belhassan Wazzani and other nationalist and Muslim leaders.

Reflecting those misgivings, Sultan Mohammed V of Morocco declined to attend the funeral on the Residence grounds on 1935-10-31, when Lyautey's remains were eventually placed in the completed mausoleum, even though he participated in a ceremony earlier the same day at Bab er-Rouah in downtown Rabat.

[66] Following Moroccan independence, French President Charles de Gaulle and Mohammed V, by then the King of Morocco, agreed to preempt the risk of incidents around the still controversial mausoleum and to repatriate Lyautey's remains, which were ceremoniously removed on 1961-04-22 and shipped to France via Casablanca.

There, his remains lie in an ornamented casket designed by Albert Laprade, the Residence's original architect almost a half-century earlier, and made by celebrated art deco metalworker Raymond Subes [fr].