Louisiana Purchase

Acquisition of Louisiana was a long-term goal of President Thomas Jefferson, who was especially eager to gain control of the crucial Mississippi River port of New Orleans.

Negotiating with French Treasury Minister François Barbé-Marbois, the U.S. representatives quickly agreed to purchase the entire territory of Louisiana after it was offered.

Overcoming the opposition of the Federalist Party, Jefferson and Secretary of State James Madison persuaded Congress to ratify and fund the Louisiana Purchase.

[6] The colony was the most substantial presence of France's overseas empire, with other possessions consisting of a few small settlements along the Mississippi and other main rivers.

Pinckney's Treaty, signed with Spain on October 27, 1795, gave American merchants "right of deposit" in New Orleans, granting them use of the port to store goods for export.

In 1801, Spanish Governor Don Juan Manuel de Salcedo took over from the Marquess of Casa Calvo, and restored the American right to deposit goods.

[10] While the treaty between Spain and France went largely unnoticed in 1800, fear of an eventual French invasion spread across America when, in 1801, Napoleon sent a military force to nearby Saint-Domingue.

[11] In 1801, Jefferson supported France in its plan to take back Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti), which was then under control of Toussaint Louverture after a slave rebellion.

[13] In January 1802, France sent General Charles Leclerc, Napoleon's brother-in-law, on an expedition to Saint-Domingue to reassert French control over the colony, which had become essentially autonomous under Louverture.

[12] In 1803, Pierre Samuel du Pont de Nemours, a French nobleman, began to help negotiate with France at the request of Jefferson.

[21] The Americans thought that Napoleon might withdraw the offer at any time, preventing the United States from acquiring New Orleans, so they agreed and signed the Louisiana Purchase Treaty on April 30, 1803 (10 Floréal XI in the French Republican calendar) at the Hôtel Tubeuf in Paris.

[26] The Louisiana Territory was vast, stretching from the Gulf of Mexico in the south to Rupert's Land in the north, and from the Mississippi River in the east to the Rocky Mountains in the west.

[27] In 1804, Haiti declared its independence; but fearing a slave revolt at home, Jefferson and the rest of Congress refused to recognize the new republic, the second in the Western Hemisphere, and imposed a trade embargo against it.

This, together with the successful French demand for an indemnity of 150 million francs in 1825, severely hampered Haiti's ability to repair its economy after decades of war.

The Federalists strongly opposed the purchase, because of the cost involved, their belief that France would not have been able to resist U.S. and British encroachment into Louisiana, and Jefferson's perceived hypocrisy.

[32] The Federalists also feared that the power of the Atlantic seaboard states would be threatened by the new citizens in the West, whose political and economic priorities were bound to conflict with those of the merchants and bankers of New England.

[34][35] Another concern was whether it was proper to grant citizenship to the French, Spanish, and free black people living in New Orleans, as the treaty would dictate.

[40] Other historians counter the above arguments regarding Jefferson's alleged hypocrisy by asserting that countries change their borders in two ways: (1) conquest, or (2) an agreement between nations, otherwise known as a treaty.

Jefferson, as a strict constructionist, was right to be concerned about staying within the bounds of the Constitution, but felt the power of these arguments and was willing to "acquiesce with satisfaction" if the Congress approved the treaty.

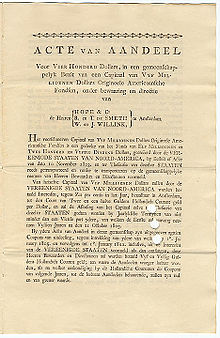

[34] The fledgling United States did not have $15 million in its treasury; instead, it borrowed the sum from British and Dutch banks, at an annual interest rate of six percent.

In legislation enacted on October 31, Congress made temporary provisions for local civil government to continue as it had under French and Spanish rule and authorized the president to use military forces to maintain order.

[29] France turned over New Orleans, the historic colonial capital, on December 20, 1803, at the Cabildo, with a flag-raising ceremony in the Plaza de Armas, now Jackson Square.

From March 10 to September 30, 1804, Upper Louisiana was supervised as a military district, under its first civil commandant, Amos Stoddard, who was appointed by the War Department.

[58] The U.S. claimed that Louisiana included the entire western portion of the Mississippi River drainage basin to the crest of the Rocky Mountains and land extending to the Rio Grande and West Florida.

[64] Because the western boundary was contested at the time of the purchase, President Jefferson immediately began to organize four missions to explore and map the new territory.

[67] The Louisiana Territory was broken into smaller portions for administration, and the territories passed slavery laws similar to those in the southern states but incorporating provisions from the preceding French and Spanish rule (for instance, Spain had prohibited slavery of Native Americans in 1769, but some slaves of mixed African–Native American descent were still being held in St. Louis in Upper Louisiana when the U.S. took over).

[69] After the early explorations, the U.S. government sought to establish control of the region, since trade along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers was still dominated by British and French traders from Canada and allied Indians, especially the Sauk and Fox.

The four decades following the Louisiana Purchase was an era of court decisions removing many tribes from their lands east of the Mississippi for resettlement in the new territory, culminating in the Trail of Tears.

The many court cases and tribal suits in the 1930s for historical damages flowing from the Louisiana Purchase led to the Indian Claims Commission Act (ICCA) in 1946.

Felix S. Cohen, Interior Department lawyer who helped pass ICCA, is often quoted as saying, "practically all of the real estate acquired by the United States since 1776 was purchased not from Napoleon or any other emperor or czar but from its original Indian owners".