Louisville and Portland Canal

The Falls form the only barrier to navigation between the origin of the Ohio at Pittsburgh and the port of New Orleans near the Gulf of Mexico; circumventing them was long a goal for Pennsylvanian and Cincinnatian merchants.

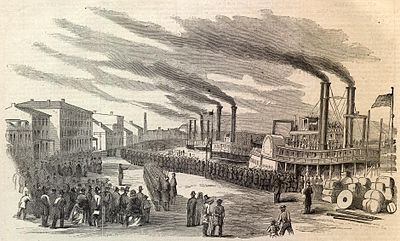

Some of the earliest cities in Kentucky – Louisville, Portland, and Shippingport – developed from the need for portage of cargo around the rapids, except during a few weeks each spring when water on the river was very high.

[5] The first meeting of the trustees of the Town of Louisville on February 7, 1781, adopted a petition to the Virginia General Assembly for the right to construct a canal around the falls.

[6] Serious plans for a canal circulated throughout the early 1800s, with Cincinnatians in particular advocating a northern route through Indiana in order to blunt competition from Louisville.

[7] Rumors that the Indiana dam had been sabotaged arose from the risk a canal posed to much of Louisville's economy, including not only forwarding, storage, drayage, and shipping but also provisioning, financing, hotels, and entertainment.

[2] This private, out-of-state ownership was praised at the time by Louisville's leading newspaper, the Public Advertiser, which said "no one is now apprehensive of any imprudent or unjust action on the part of the Legislature".

Its 50-foot (15 m) wide dimensions were huge in comparison with projects like the Erie Canal and intended to permit full-sized ships to pass from one side of the falls to the other.

Nevertheless, the growing power and size of steamboats left the canal nearly obsolete soon after opening at the same time that the Alabama Fever and booming Black Belt cotton plantations increased demand for produce and goods from the north.

The company's high tolls and disinterest in improving the canal either to enlarge it or to correct the lower end, which opened into a narrow part of the river with a swift current, provoked dissatisfaction among its customers.

[13] The company's management opted to solve the problem on their own: instead of funding expansions, improvements, or dividends, profits from the canal were used to purchase privately held shares at a premium, gradually increasing the government's ownership stake.

[2] Despite holding full ownership of the company after 1855, the federal government found it impossible to get Congress to approve taking formal control of the canal.

The facility was a target of Confederate forces in Kentucky, at least one of whom advocated destroying it so "future travelers would hardly know where it was",[16] but Union control of the state rendered the threat moot.

In May 1874, Congress passed a bill allowing the Corps of Engineers to take full control of the canal and authorizing the Treasury to pay off the bonds for the recent improvements.

In 1880, under political pressure from upriver producers, Congress removed the canal's tolls entirely, forgoing profit and paying the entirety of its expenses from the Treasury.

Portland, after initially continuing to grow and incorporating separately in 1834, accepted a proposal to widen the canal and annexation to west Louisville in 1837 in exchange for its wharf becoming the terminus of the Lexington and Ohio Railroad; when the western line of the railroad only managed to successfully connect Portland with Louisville before its 1840 bankruptcy, the community removed itself again from 1842 to 1852, before accepting reannexation.