Lumped-element model

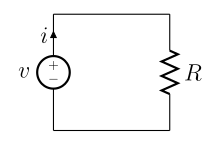

The lumped-element model simplifies the system or circuit behavior description into a topology.

The simplification reduces the state space of the system to a finite dimension, and the partial differential equations (PDEs) of the continuous (infinite-dimensional) time and space model of the physical system into ordinary differential equations (ODEs) with a finite number of parameters.

The lumped-matter discipline is a set of imposed assumptions in electrical engineering that provides the foundation for lumped-circuit abstraction used in network analysis.

Less severe assumptions result in the distributed-element model, while still not requiring the direct application of the full Maxwell equations.

The lumped-element model of electronic circuits makes the simplifying assumption that the attributes of the circuit, resistance, capacitance, inductance, and gain, are concentrated into idealized electrical components; resistors, capacitors, and inductors, etc.

The exact point at which the lumped-element model can no longer be used depends to a certain extent on how accurately the signal needs to be known in a given application.

This in turn leads to simple exponential heating or cooling behavior (details below).

The Biot number must generally be less than 0.1 for usefully accurate approximation and heat transfer analysis.

A Biot number greater than 0.1 (a "thermally thick" substance) indicates that one cannot make this assumption, and more complicated heat transfer equations for "transient heat conduction" will be required to describe the time-varying and non-spatially-uniform temperature field within the material body.

A useful concept used in heat transfer applications once the condition of steady state heat conduction has been reached, is the representation of thermal transfer by what is known as thermal circuits.

The values of the thermal resistance for the different modes of heat transfer are then calculated as the denominators of the developed equations.

The lack of "capacitative" elements in the following purely resistive example, means that no section of the circuit is absorbing energy or changing in distribution of temperature.

Using the thermal resistance concept, heat flow through the composite is as follows:

On a cold day, a warm home will leak heat to the outside at a greater rate when there is a large difference between the inside and outside temperatures.

Note that the rate of cooling experienced on a cold day can be increased by the added convection effect of the wind.

In such situations, heat can be transferred from the exterior to the interior of a body, across the insulating boundary, by convection, conduction, or diffusion, so long as the boundary serves as a relatively poor conductor with regard to the object's interior.

The presence of a physical insulator is not required, so long as the process which serves to pass heat across the boundary is "slow" in comparison to the conductive transfer of heat inside the body (or inside the region of interest—the "lump" described above).

In electrical circuits, such a combination would charge or discharge toward the input voltage, according to a simple exponential law in time.

Newton's law is mathematically stated by the simple first-order differential equation:

It is expected that the system will experience exponential decay with time in the temperature of a body.

The solution of this differential equation, by standard methods of integration and substitution of boundary conditions, gives:

This same solution is almost immediately apparent if the initial differential equation is written in terms of

This mode of analysis has been applied to forensic sciences to analyze the time of death of humans.

Also, it can be applied to HVAC (heating, ventilating and air-conditioning, which can be referred to as "building climate control"), to ensure more nearly instantaneous effects of a change in comfort level setting.

[3] The simplifying assumptions in this domain are: In this context, the lumped-component model extends the distributed concepts of acoustic theory subject to approximation.

A simplifying assumption in this domain is that all heat transfer mechanisms are linear, implying that radiation and convection are linearised for each problem.

Several publications can be found that describe how to generate lumped-element models of buildings.

[5] Lumped-element models of buildings have also been used to evaluate the efficiency of domestic energy systems, by running many simulations under different future weather scenarios.

[6] Fluid systems can be described by means of lumped-element cardiovascular models by using voltage to represent pressure and current to represent flow; identical equations from the electrical circuit representation are valid after substituting these two variables.

Such applications can, for example, study the response of the human cardiovascular system to ventricular assist device implantation.