Electrical impedance

In electrical engineering, impedance is the opposition to alternating current presented by the combined effect of resistance and reactance in a circuit.

The notion of impedance is useful for performing AC analysis of electrical networks, because it allows relating sinusoidal voltages and currents by a simple linear law.

Perhaps the earliest use of complex numbers in circuit analysis was by Johann Victor Wietlisbach in 1879 in analysing the Maxwell bridge.

Wietlisbach avoided using differential equations by expressing AC currents and voltages as exponential functions with imaginary exponents (see § Validity of complex representation).

Wietlisbach found the required voltage was given by multiplying the current by a complex number (impedance), although he did not identify this as a general parameter in its own right.

Kennelly arrived at a complex number representation in a rather more direct way than using imaginary exponential functions.

[8][9] Later that same year, Kennelly's work was generalised to all AC circuits by Charles Proteus Steinmetz.

[11] In addition to resistance as seen in DC circuits, impedance in AC circuits includes the effects of the induction of voltages in conductors by the magnetic fields (inductance), and the electrostatic storage of charge induced by voltages between conductors (capacitance).

To simplify calculations, sinusoidal voltage and current waves are commonly represented as complex-valued functions of time denoted as

At the end of any calculation, we may return to real-valued sinusoids by further noting that The meaning of electrical impedance can be understood by substituting it into Ohm's law.

Phasors are used by electrical engineers to simplify computations involving sinusoids (such as in AC circuits[12]: 53 ), where they can often reduce a differential equation problem to an algebraic one.

Note the following identities for the imaginary unit and its reciprocal: Thus the inductor and capacitor impedance equations can be rewritten in polar form: The magnitude gives the change in voltage amplitude for a given current amplitude through the impedance, while the exponential factors give the phase relationship.

In fact, this applies to any arbitrary periodic signals, because these can be approximated as a sum of sinusoids through Fourier analysis.

This result is commonly expressed as For a capacitor, there is the relation: Considering the voltage signal to be it follows that and thus, as previously, Conversely, if the current through the circuit is assumed to be sinusoidal, its complex representation being then integrating the differential equation leads to The Const term represents a fixed potential bias superimposed to the AC sinusoidal potential, that plays no role in AC analysis.

For this purpose, this term can be assumed to be 0, hence again the impedance For the inductor, we have the relation (from Faraday's law): This time, considering the current signal to be: it follows that: This result is commonly expressed in polar form as or, using Euler's formula, as As in the case of capacitors, it is also possible to derive this formula directly from the complex representations of the voltages and currents, or by assuming a sinusoidal voltage between the two poles of the inductor.

In the latter case, integrating the differential equation above leads to a constant term for the current, that represents a fixed DC bias flowing through the inductor.

Impedance defined in terms of jω can strictly be applied only to circuits that are driven with a steady-state AC signal.

The concept of impedance can be extended to a circuit energised with any arbitrary signal by using complex frequency instead of jω.

In the phasor regime (steady-state AC, meaning all signals are represented mathematically as simple complex exponentials

), impedance can simply be calculated as the voltage-to-current ratio, in which the common time-dependent factor cancels out: Again, for a capacitor, one gets that

[17] For steady-state AC, the polar form of the complex impedance relates the amplitude and phase of the voltage and current.

is the imaginary part of the impedance; a component with a finite reactance induces a phase shift

A constant direct current has a zero rate-of-change, and sees an inductor as a short-circuit (it is typically made from a material with a low resistivity).

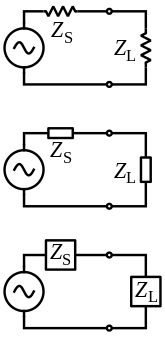

The general case, however, requires equivalent impedance transforms in addition to series and parallel.

[18] The measurement of the impedance of devices and transmission lines is a practical problem in radio technology and other fields.

Performing this measurement by sweeping the frequencies of the applied signal provides the impedance phase and magnitude.

is minimal (actually equal to 0 in this case) whenever Therefore, the fundamental resonance angular frequency is In general, neither impedance nor admittance can vary with time, since they are defined for complex exponentials in which −∞ < t < +∞.

If the complex exponential voltage to current ratio changes over time or amplitude, the circuit element cannot be described using the frequency domain.

However, many components and systems (e.g., varicaps that are used in radio tuners) may exhibit non-linear or time-varying voltage to current ratios that seem to be linear time-invariant (LTI) for small signals and over small observation windows, so they can be roughly described as if they had a time-varying impedance.

This description is an approximation: Over large signal swings or wide observation windows, the voltage to current relationship will not be LTI and cannot be described by impedance.