Lughnasadh

Lughnasadh, Lughnasa or Lúnasa (/ˈluːnəsə/ LOO-nə-sə, Irish: [ˈl̪ˠuːnˠəsˠə]) is a Gaelic festival marking the beginning of the harvest season.

In the Middle Ages, it involved great gatherings that included ceremonies, athletic contests (most notably the Tailteann Games), horse racing, feasting, matchmaking, and trading.

According to folklorist Máire MacNeill, evidence suggests that the religious rites included an offering of the First Fruits, a feast of the new food, the sacrifice of a bull, and a ritual dance-play.

In recent centuries, Lughnasadh gatherings have typically been held on top of hills and mountains, including many of the same activities.

In Irish mythology, Lughnasadh is said to have been founded by the god Lugh as a funeral feast and athletic competition—funeral games—to commemorate the death of an earth goddess.

[10] A story about the Lughnasadh site of Tailtin says the festival was founded by Lugh as funeral games in memory of his foster-mother Tailtiu.

[13] Another tale, about the assembly site of Naas, says that Lugh founded the festival in memory of his two wives, the sisters Nás and Bói.

[17] MacNeill says that these themes can be seen in earlier Irish mythology, particularly in the tale of Lugh defeating Balor,[17] which seems to represent the overcoming of blight, drought and the scorching summer sun.

[17] He may be based on an underworld god like Hades and Pluto, who kidnaps the grain goddess Persephone but is forced to let her return to the world above before harvest time.

It was similar to the Ancient Olympic Games and included ritual athletic and sporting contests, horse racing, music and storytelling, trading, proclaiming laws and settling legal disputes, drawing-up contracts, and matchmaking.

[21] A 15th-century version of the Irish legend Tochmarc Emire ("the Wooing of Emer") is one of the earliest documents to record these festivities.

[32] MacNeill studied surviving Lughnasadh customs and folklore as well as the earlier accounts and medieval writings about the festival.

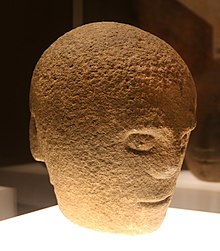

She concluded that the evidence testified to the existence of an ancient festival around 1 August that involved the following: A solemn cutting of the first of the corn of which an offering would be made to the deity by bringing it up to a high place and burying it; a meal of the new food and of bilberries of which everyone must partake; a sacrifice of a sacred bull, a feast of its flesh, with some ceremony involving its hide, and its replacement by a young bull; a ritual dance-play perhaps telling of a struggle for a goddess and a ritual fight; an installation of a [carved stone] head on top of the hill and a triumphing over it by an actor impersonating Lugh; another play representing the confinement by Lugh of the monster blight or famine; a three-day celebration presided over by the brilliant young god [Lugh] or his human representative.

[33]Many of the customs described by medieval writers survived into the modern era, though they were either Christianized or shorn of any pagan religious meaning.

On the Iveragh Peninsula, a pilgrimage to the summit of Drung Hill was part of local Lughnasadh celebrations until it died out around 1880.

[36] In Ireland, bilberries were gathered[37] and there was eating, drinking, dancing, folk music, games and matchmaking, as well as athletic and sporting contests such as weight-throwing, hurling and horse racing.

It is believed this is because the coming of the harvest was a busy time and the weather could be unpredictable, which meant work days were too important to give up.

The festival includes traditional music and dancing, a parade, arts and crafts workshops, a horse and cattle fair, and a market.

Craggaunowen, an open-air museum in County Clare, hosts a yearly Lughnasa Festival at which historical re-enactors demonstrate elements of daily life in Gaelic Ireland.

[64][65][66][67][68] Some neopagans celebrate it at the astronomical midpoint between the summer solstice and autumn equinox, or the full moon nearest this point.

In the Northeastern United States, this is often the time of the blueberry harvest, while in the Pacific Northwest the blackberries are often the festival fruit.

[25][71] In Celtic Reconstructionism, Lughnasadh is seen as a time to give thanks to the spirits and deities for the beginning of the harvest season, and to propitiate them with offerings and prayers not to harm the still-ripening crops.

The god Lugh is honoured by many at this time, and gentle rain on the day of the festival is seen as his presence and his bestowing of blessings.

Many Celtic Reconstructionists also honour the goddess Tailtiu at Lughnasadh, and may seek to keep the Cailleachan from damaging the crops, much in the way appeals are made to Lugh.