Red Line (MBTA)

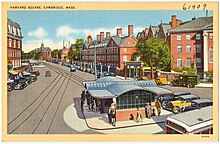

Construction of the Cambridge tunnel, connecting Harvard Square to Boston, was delayed by a dispute over the number of intermediate stations to be built along the new line.

[further explanation needed][2]: 41 The section from Harvard (and new maintenance facilities at Eliot Yard) to Park Street was opened by the Boston Elevated Railway (BERy) on March 23, 1912.

The New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad succeeded the Old Colony in operating the branch, but passenger service ceased on September 4, 1926, in anticipation of the construction of the BERy's Dorchester extension.

[3] The BERy opened the first phase of the Dorchester extension, to Fields Corner station, on November 5, 1927, south from Andrew, then southeast to the surface and along the west side of the Old Colony mainline in a depressed right-of-way.

[6] In January 1981, the MBTA proposed to close the Ashmont branch on Sundays – and the Mattapan Line at all times – beginning that March due to severe budget issues.

[12] On July 28, 1965, the MBTA signed an agreement with the New Haven Railroad to purchase 11 miles (18 km) of the former Old Colony mainline from Fort Point Channel to South Braintree in order to construct a new rapid transit line along the corridor.

Several outlying sections of the MBTA subway system, including Quincy Adams and Braintree, originally charged a double fare to account for the additional costs of running service far from downtown.

[20] By 1922, the BERy believed that Harvard would be the permanent terminus; the heavy ridership from the north was expected to be handled by extending rapid transit from Lechmere Square.

[22] A northwards extension from Harvard to the North Cambridge/Arlington border was proposed by Cambridge mayor John D. Lynch in 1933 and by then-freshmen state representative Tip O'Neill in 1936, but was not pursued.

[23] The 1945 Coolidge Commission report – the first major transit planning initiative in the region since 1926 – recommended an extension from Harvard to Arlington Heights via East Watertown.

[31] The Environmental Impact Statement, released in August 1977, primarily evaluated the Arlington Heights terminus but also provided for a shorter Alewife extension.

[28][32] By the time the northwest extension began construction in 1978, opposition in Arlington and reductions in federal funding had caused the MBTA to choose the shorter Alewife alternative.

[6] A $255 million project, which started in Spring 2013, replaced structural elements of the Longfellow Bridge, which carries the line across the Charles River between the Charles/MGH and Kendall/MIT stations.

The aboveground sections of the Orange and Red lines were particularly vulnerable due to their exposed third rail power feed, which iced over during storms.

(Because the Blue Line was built with overhead catenary on its surface section due to its exposure to corrosive salt air, it was not as easily disabled by the icing conditions.)

During 2015, the MBTA implemented its $83.7 million Winter Resiliency Program, much of which focused on preventing similar vulnerabilities with the Orange and Red lines.

[50] In July 2016, the MBTA Fiscal and Management Control Board approved a $18.5 million contract to complete work along the remainder of the southern branches.

[53] On December 10, 2015, a Red Line train in revenue service traveled from Braintree to North Quincy without an operator in the cab before it was stopped by cutting power to the third rail.

In 1985 the entire Red Line was converted to the new cab signal standard with any remaining interlocking towers being closed with a relay based centralized traffic control machine being installed in a dispatch office at 45 High Street.

This in turn was replaced in the late 1990s with a software-controlled Automatic Train Supervision product by Union Switch & Signal, subcontracted to Syseca Inc. (now ARINC), in a new control room.

[71] In October 2018, the MBTA awarded a $218 million improved signal contract for the Red and Orange Lines, which will allow 3-minute headways between JFK/UMass and Alewife beginning in 2022.

[73] The Red Line experienced major service disruptions in the winter of 2014–15 due to frozen-over third rails, leaving unpowered trains stranded between stations with passengers on board.

(East Boston Tunnel cars accessed the yard through the now-closed Joy Street portal near Bowdoin station and a track connection on the Longfellow Bridge).

They had a novel design as a result of studies about Boston's existing lines, with a then-extraordinary length of 69 feet 6 inches (21.18 m) over buffers, and a large standee capacity, while weighing only 85,900 pounds (38,964 kg).

Before their overhauls, the 1500 and 1600 series had a brushed aluminum livery with a thin red stripe and were usually called "Silverbird" cars from their natural metal finish.

In December 2008, the MBTA began running a pair of modified 1800 series cars without seats, in order to increase train capacity.

The Board forwent federal funding to allow the contract to specify the cars be built in Massachusetts, to create a local railcar manufacturing industry.

[87] In conjunction with the new rolling stock, the remainder of the $1.3 billion allocated for the project will pay for testing, signal improvements and expanded maintenance facilities, as well as other related expenses.

Combined, the 2014 and 2016 orders will provide a single common fleet for the entire Red Line, with enough cars to eventually run 3-minute headways at peak.

[104] Newer aboveground stations (particularly Alewife, Braintree, and Quincy Adams, which all have large parking garages) are excellent examples of brutalist architecture.