Rapid transit

A grade separated rapid transit line below ground surface through a tunnel can be regionally called a subway, tube, metro or underground.

[8] Modern services on rapid transit systems are provided on designated lines between stations typically using electric multiple units on railway tracks.

In Northern Europe, rapid transit systems are called metro in Copenhagen (Denmark) and Helsinki (Finland), while they are refferd to as T-bane (tunnelbane) in Oslo (Norway) and tunnelbana in Stockholm (Sweden).

[37] The technology quickly spread to other cities in Europe, the United States, Argentina, and Canada, with some railways being converted from steam and others being designed to be electric from the outset.

However, much higher capacities are attained in East Asia with ranges of 75,000 to 85,000 people per hour achieved by MTR Corporation's urban lines in Hong Kong.

[54][55][56] Rapid transit topologies are determined by a large number of factors, including geographical barriers, existing or expected travel patterns, construction costs, politics, and historical constraints.

[58] Rapid transit operators have often built up strong brands, often focused on easy recognition – to allow quick identification even in the vast array of signage found in large cities – combined with the desire to communicate speed, safety, and authority.

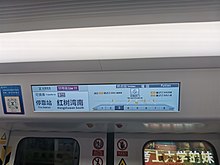

In addition to online maps and timetables, some transit operators now offer real-time information which allows passengers to know when the next vehicle will arrive, and expected travel times.

Rapid transit systems have been subject to terrorism with many casualties, such as the 1995 Tokyo subway sarin gas attack[67] and the 2005 "7/7" terrorist bombings on the London Underground.

Some rapid transport trains have extra features such as wall sockets, cellular reception, typically using a leaky feeder in tunnels and DAS antennas in stations, as well as Wi-Fi connectivity.

[68] Many metro systems, such as the Hong Kong Mass Transit Railway (MTR) and the Berlin U-Bahn, provide mobile data connections in their tunnels for various network operators.

Historically, rapid transit trains used ceiling fans and openable windows to provide fresh air and piston-effect wind cooling to riders.

From the 1950s to the 1990s (and in most of Europe until the 2000s), many rapid transit trains from that era were also fitted with forced-air ventilation systems in carriage ceiling units for passenger comfort.

Especially in some rapid transit systems such as the Montreal Metro[76] (opened 1966) and Sapporo Municipal Subway (opened 1971), their entirely enclosed nature due to their use of rubber-tyred technology to cope with heavy snowfall experienced by both cities in winter precludes any air-conditioning retrofits of rolling stock due to the risk of heating the tunnels to temperatures that would be too hot for passengers and for train operations.

Although these sub-networks may not often be connected by track, in cases when it is necessary, rolling stock with a smaller loading gauge from one sub network may be transported along other lines that use larger trains.

An alternate technology, using rubber tires on narrow concrete or steel roll ways, was pioneered on certain lines of the Paris Métro and Mexico City Metro, and the first completely new system to use it was in Montreal, Canada.

Advocates of this system note that it is much quieter than conventional steel-wheeled trains, and allows for greater inclines given the increased traction of the rubber tires.

They also lose traction when weather conditions are wet or icy, preventing above-ground use of the Montréal Metro and limiting it on the Sapporo Municipal Subway, but not rubber-tired systems in other cities.

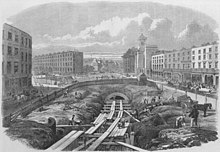

In one common method, known as cut-and-cover the city streets are excavated and a tunnel structure strong enough to support the road above is built in the trench, which is then filled in and the roadway rebuilt.

This method often involves extensive relocation of utilities commonly buried not far below street level – particularly power and telephone wiring, water and gas mains, and sewers.

Among the possible candidates are: An advantage of deep tunnels is that they can dip in a basin-like profile between stations, without incurring the significant extra costs associated with digging near ground level.

Particularly in the former Soviet Union and other Eastern European countries, but to an increasing extent elsewhere, the stations were built with splendid decorations such as marble walls, polished granite floors and mosaics—thus exposing the public to art in their everyday life, outside galleries and museums.

[87] It may be possible to profit by attracting more passengers by spending relatively small amounts on grand architecture, art, cleanliness, accessibility, lighting and a feeling of safety.

This style of "semi-automatic train operation" (STO), known technically as "Grade of Automation (GoA) 2", has become widespread, especially on newly built lines like the San Francisco Bay Area's BART network.

A variant of ATO, "driverless train operation" (DTO) or technically "GoA 3", is seen on some systems, as in London's Docklands Light Railway, which opened in 1987.

In some cities, the same reasons are used to justify a crew of two rather than one; one person drives from the front of the train, while the other operates the doors from a position farther back, and is more conveniently able to assist passengers in the rear cars.

While this demonstrates that those technological hurdles can be overcome, the project was severely delayed, missing the target of being in operation in time for the 2006 FIFA World Cup and the hoped for international orders for the system of automation employed in Nuremberg never materialized.

Both new and upgraded tram systems allow faster speed and higher capacity, and are a cheap alternative to construction of rapid transit, especially in smaller cities.

The suburban systems may have their own purpose built trackage, run at similar "rapid transit-like" frequencies, and (in many countries) are operated by the national railway company.

This ignores both heavy capital costs incurred in building the system, which are often funded with soft loans[99] and whose servicing is excluded from calculations of profitability, as well as ancillary revenue such as income from real estate portfolios.