Mach tuck

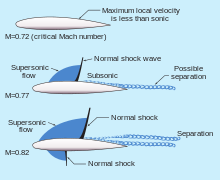

Mach tuck is an aerodynamic effect whereby the nose of an aircraft tends to pitch downward as the airflow around the wing reaches supersonic speeds.

The changing airflow over the wing can reduce the downwash over a conventional tailplane, promoting a stronger nose-down pitching moment.

Aircraft without enough elevator authority to maintain trim and fly level can enter a steep, sometimes unrecoverable dive.

[6] Until the aircraft is supersonic, the faster top shock wave can reduce the authority of the elevator and horizontal stabilizers.

In place of the conventional elevator control surface, the whole stabiliser may be made moveable or "all-flying", sometimes called a stabilator.

This both increases the authority of the stabilizer over a wider range of aircraft pitch, but also avoids the controllability issues associated with a separate elevator.

[7] Aircraft that fly supersonic for long periods, such as Concorde, may compensate for Mach tuck by moving fuel between tanks in the fuselage to change the position of the centre of mass to match the changing location of the centre of pressure, thereby minimizing the amount of aerodynamic trim required.

[11] It had a thick, high-lift wing, distinctive twin booms and a single, central nacelle containing the cockpit and armament.

The resultant change in downwash at the tail caused a nose-down pitching moment and the dive to steepen (Mach tuck).