Madrasa

The origin of this type of institution is widely credited to Nizam al-Mulk, a vizier under the Seljuks in the 11th century, who was responsible for building the first network of official madrasas in Iran, Mesopotamia, and Khorasan.

[9] The word madrasah derives from the triconsonantal Semitic root د-ر-س D-R-S 'to learn, study', using the wazn (morphological form or template) مفعل(ة); mafʻal(ah), meaning "a place where something is done".

Niẓām al-Mulk, who would later be murdered by the Assassins (Ḥashshāshīn), created a system of state madrasas (in his time they were called the Niẓāmiyyahs, named after him) in various Seljuk and ʻAbbāsid cities at the end of the 11th century, ranging from Mesopotamia to Khorasan.

[8][6] Although madrasa-type institutions appear to have existed in Iran before Nizam al-Mulk, this period is nonetheless considered by many as the starting point for the proliferation of the formal madrasah across the rest of the Muslim world, adapted for use by all four different Sunni Islamic legal schools and Sufi orders.

[28] Under the Anatolian Seljuk, Zengid, Ayyubid, and Mamluk dynasties (11th-16th centuries) in the Middle East, many of the ruling elite founded madrasas through a religious endowment and charitable trust known as a waqf.

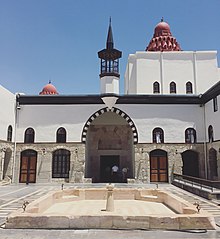

During the Ottoman period the medrese (Turkish word for madrasah) was a common institution as well, often part of a larger külliye or a waqf-based religious foundation which included other elements like a mosque and a hammam (public bathhouse).

He wrote that children can learn better if taught in classes instead of individual tuition from private tutors, and he gave a number of reasons for why this is the case, citing the value of competition and emulation among pupils, as well as the usefulness of group discussions and debates.

[56] However, in an earlier article, he considered the ijāzah to be of "fundamental difference" to the medieval doctorate, since the former was awarded by an individual teacher-scholar not obliged to follow any formal criteria, whereas the latter was conferred on the student by the collective authority of the faculty.

[67][68] Darleen Pryds questions this view, pointing out that madrasas and European universities in the Mediterranean region shared similar foundations by princely patrons and were intended to provide loyal administrators to further the rulers' agenda.

[100] The other, al-Azhar, did acquire this status in name and essence only in the course of numerous reforms during the 19th and 20th century, notably the one of 1961 which introduced non-religious subjects to its curriculum, such as economics, engineering, medicine, and agriculture.

[107] Norman Daniel criticizes Makdisi for overstating his case by simply resting on "the accumulation of close parallels" while failing to point to convincing channels of transmission between the Muslim and Christian world.

[108] Daniel also points out that the Arab equivalent of the Latin disputation, the taliqa, was reserved for the ruler's court, not the madrasa, and that the actual differences between Islamic fiqh and medieval European civil law were profound.

According to Saliba:[112] As I noted in my original article, students in the medieval Islamic world, who had the full freedom to chose their teacher and the subjects that they would study together, could not have been worse off than today’s students, who are required to pursue a specific curriculum that is usually designed to promote the ideas of their elders and preserve tradition, rather than introduce them to innovative ideas that challenge ‘received texts.’ Moreover, if Professor Huff had looked more carefully at the European institutions that produced science, he would have found that they were mainly academies and royal courts protected by individual potentates and not the universities that he wishes to promote.

Another female (albeit probably fictional) figure to be remembered for her achievements was Tawaddud, "a slave girl who was said to have been bought at great cost by Hārūn al-Rashīd because she had passed her examinations by the most eminent scholars in astronomy, medicine, law, philosophy, music, history, Arabic grammar, literature, theology and chess".

Nonetheless, it is clear that the Seljuks constructed many madrasas across their empire within a relatively short period of time, thus spreading both the idea of this institution and the architectural models on which later examples were based.

Many of their projects involved the construction of madrasas as part of larger multi-functional religious complexes, usually attached to their personal mausoleums, which provided services to the general population while also promoting their own prestige and pious reputations.

Moreover, due to the already dense urban fabric of Cairo, Mamluk architectural complexes adopted increasingly irregular and creatively designed floor plans to compensate for limited space while simultaneously attempting to maximize their prominence and visibility from the street.

However, the most significant Mamluk archtiectural patronage outside of Cairo is likely in Jerusalem, as with the example of the major al-Ashrafiyya Madrasa on the Temple Mount (Haram al-Sharif), which was rebuilt in its current form by Sultan Qaytbay in the late 15th century.

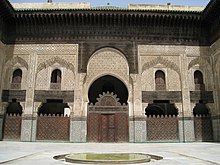

[37] In Morocco, madrasas were generally built in brick and wood and were still centered around a main internal courtyard with a central fountain or water basin, around which student dorms were distributed across one or two floors.

The Timurid period (late 14th and 15th century), however, was a "golden age" of Iranian madrasas, during which the four-iwan model was made much larger and more monumental, on a par with major mosques, thanks to intense patronage from Timur and his successors.

In northwestern Africa (the Maghrib or Maghreb), including Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, the appearance of madrasas was delayed until after the fall of the Almohad dynasty, who espoused a reformist doctrine generally considered unorthodox by other Sunnis.

The Marinids used their patronage of madrasas to cultivate the loyalty of Morocco's influential but independent religious elites and also to portray themselves to the general population as protectors and promoters of orthodox Sunni Islam.

[39] A number of madrasas also played a supporting role to major learning institutions like the older Qarawiyyin Mosque-University and the al-Andalusiyyin Mosque (both located in Fes) because they provided accommodations for students coming from other cities.

The religious establishment forms part of the mainly two large divisions within the country, namely the Deobandis, who dominate in numbers (of whom the Darul Uloom Deoband constitutes one of the biggest madrasas) and the Barelvis, who also make up a sizeable portion (Sufi-oriented).

[177] Students attending a madrasah are required to wear the traditional Malay attire, including the songkok for boys and tudong for girls, in contrast to mainstream government schools which ban religious headgear as Singapore is officially a secular state.

In the Arabic language, the word madrasa (مدرسه) means any educational institution, of any description, (as does the term school in American English)[182] and does not imply a political or religious affiliation, not even one as broad as Islam in the general sense.

The Yale Center for the Study of Globalization examined bias in United States newspaper coverage of Pakistan since the September 11, 2001 attacks, and found the term has come to contain a loaded political meaning:[184] When articles mentioned "madrassas," readers were led to infer that all schools so-named are anti-American, anti-Western, pro-terrorist centres having less to do with teaching basic literacy and more to do with political indoctrination.Various American public figures in the early 2000s used the word in a negative manner, including Newt Gingrich,[184] Donald Rumsfeld,[185] and Colin Powell.

In the year 2000, an article from Foreign Affairs, authored by university professor Jessica Stern, claimed that specifically Pakistani madrasas were responsible for the development of thousands of jihadists/terrorists, and that they were essentially weapons of mass destruction.

During the time of the article's release, videos surfaced of young boys intensely memorizing/studying the Quran, thus facilitating the false stereotype that madrasas brainwash and breed children to becoming future jihadists.

We are therefore concerned with what is indisputably an original institution, which can only be defined in terms of a historical analysis of its emergence and its mode of operation in concrete circumstances.Thus the university, as a form of social organisation, was peculiar to medieval Europe.